Issam Kourbaj greets me with a handshake and a smile. The Syrian artist has just flown from London to speak about his contributions to the new exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cultures in the Crossfire: Stories from Syria and Iraq.

The exhibition combines artifacts from ancient Syria and Iraq with Issam’s own “art interventions” in response, interwoven to create narrative threads that connect his culture over centuries through material and memory. Uniting all of these objects and the stories they hold, Issam’s voice rings clear.

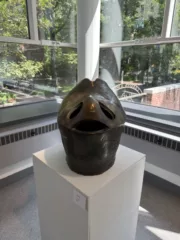

Aleppo soap

He is warm and empathetic as we walk through the gallery, surprisingly so for having just taken a red eye flight, and especially considering that just this morning (as I write this) news broke that our own government launched a missile strike on a military base in his homeland in response to the Syrian government’s gassing of his fellow Syrian civilians. This relevance is not lost on either of us, and his work with the artifacts in this exhibition proves more vital today than they would have seemed yesterday.

The works that bookend the show are haunting. First are video projections of ISIS destroying the Assyrian Palace in Nimrud, Iraq, in 2015, and Syrian President Bashar-Al-Assad’s forces destroying the minaret of the Al-Omari Mosque in Daraa, Syria, in 2013. It’s difficult, indeed painful, to watch these two architectural masterpieces be blown apart, but I can’t look away. I keep thinking that each time the video loops, the outcome will change. Of course, it doesn’t.

But the final piece in the exhibition, Issam’s “Aleppo Soap, Don’t Wash Your Hands,” is what resounds most. A mirrorless frame, a shattered sink, and a soap tray are mounted to the wall in a makeshift bathroom scene. On the tray sits a bar of “Aleppo soap,” produced in the city for centuries. Issam asks us just this–don’t wash your hands of this crisis. Aleppo is dying. Syria and Iraq are dying. Our history is dying, and when it does we all go with it. The rest of the artifacts and works in this exhibition offer context for these challenging statements.

Relics of Palmyra

Towards the beginning on the first wall, carved mortuary portraits from ancient Palmyra, Syria, are displayed in a row–priceless relics of not just the deceased, but now of Palmyra itself, also largely razed by ISIS. Next to the portraits are “before and after” color photographs of sites at Nimrud, Aleppo, and Palmyra. The cities pictured in the “after” photos are barely recognizable. This targeted destruction of cultural heritage is deliberate and motivated by religion and ethnicity–a stark contrast to the diversity that has existed there in the cradle of civilization since antiquity. Centuries ago when many of these artifacts were made Jews, Christians, Mandaeans, and Polytheists all coexisted peacefully in the Middle East. In my lifetime I know only a Middle East at war.

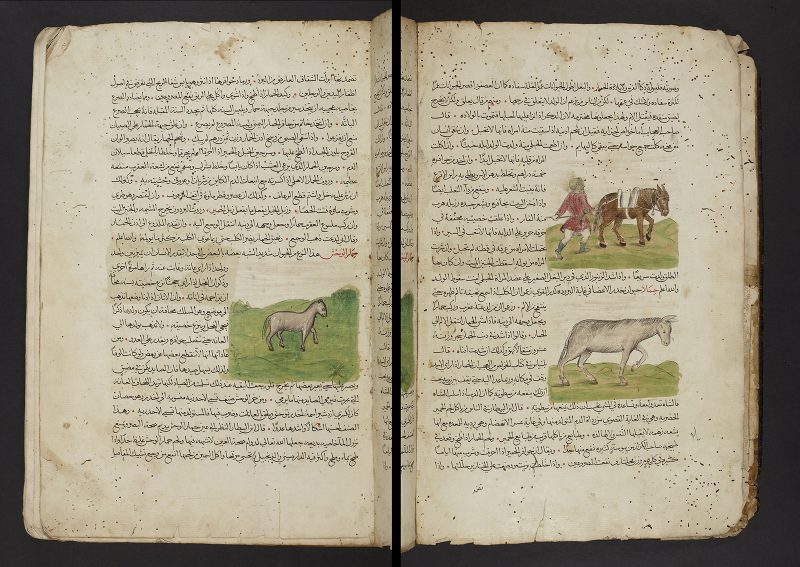

Equal attention is paid to everyday objects like serving bowls and frying pans as to lavish instruments and ornaments of the wealthy. These material connections between items draws a long narrative thread through time, bookended by Issam’s own use of material in his work to envision the past, present, and future. Some incredible manuscripts are on display, works on mathematics and zoology, dictionaries and stones carved with Assyrian poetry and stories, reminders of the intellectual mecca that this part of the world became in antiquity. The works and wares of artists and craftspeople dot the gallery, each more remarkable than the last.

The destruction of material cultural heritage, while devastating, cannot be compared to the tragic loss of human life and the creation of the human wave of displaced Syrian refugees.

Losing home

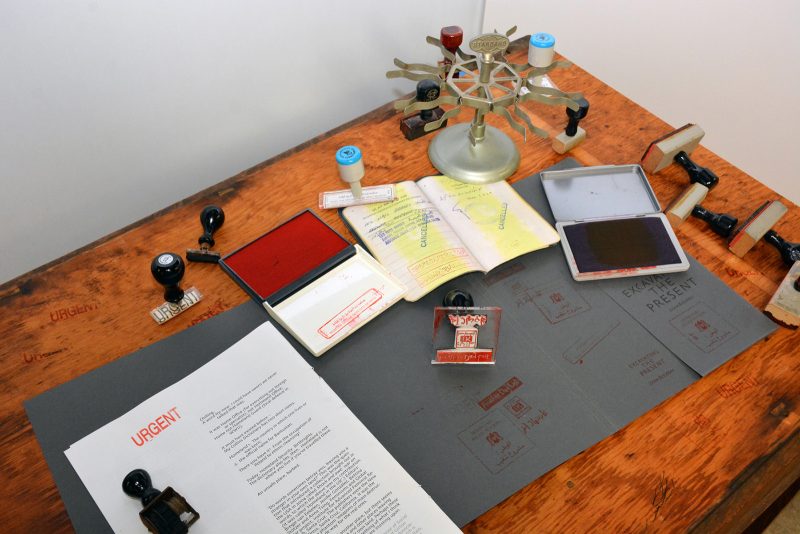

Issam knows this–he’s seen the suffering of his friends, family, and countrymen from afar, but felt it keenly. In his work “Homeland, an excavation,” he displays in a vitrine his actual Syrian passport stamped “CANCELLED.” This was his first passport, and when expired in 1991, he “had to ask for new one at the Syrian embassy in London. It was canceled by the embassy then.” Next to the passport are a number of found Syrian immigration stamps and seals from our current era of war. An object that implies freedom, his Syrian passport brought him anything but.

Issam was born in Suweida in 1963 in the south of Syria and attended the Institute of Fine Arts in Damascus. His education eventually took him to Wimbledon School of Art in England. He has lived in England with his wife and children since 1990 as a Lector and Bye-Fellow at Christ’s College, Cambridge. He has been a British citizen since 1994. Since 2003 and the invasion of Iraq by U.S. forces, the focus of Issam’s work shifted to his lost homeland and people and the stories that can be told through everyday objects and seemingly useless materials. The invasion signaled a sea change for international involvement in the Middle East, the effects of which quickly bled over into Syria, planting the seeds of ISIS and capitulating in the Syrian uprising in 2011. Issam made it out, but many of his friends and family could not escape the violence.

Although he is an observer who was lucky enough to have fled, he keeps Syria’s struggles close to the heart and actively raises money for Syrian refugees through his installations around the globe. From his exhibition Excavating the Present in Cambridge in 2013 to his traveling work, Another Day Lost, he uses his clout to contribute in a concrete way.

He recalls how his mother used to tell him to “touch the worthless and make it priceless.” A tough task, but he’s done it. His people have been made invisible, so he makes us see.

Loss and hope

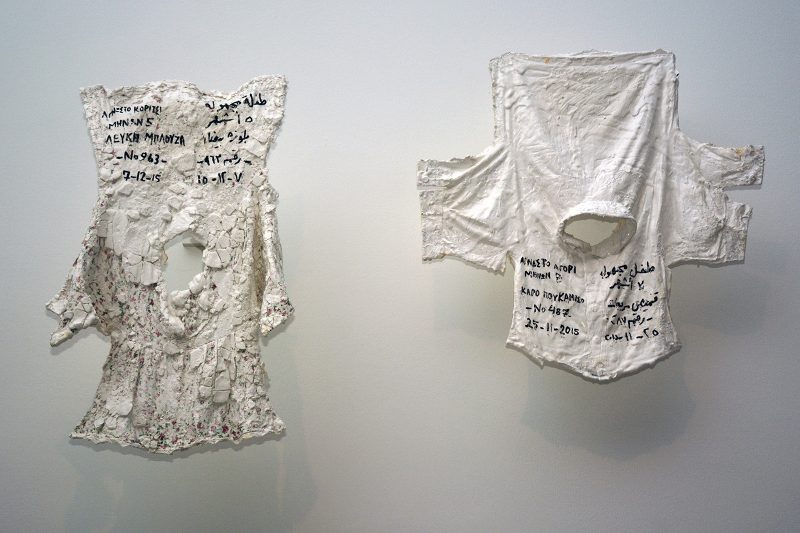

His work “Lost” is a response to the death of refugee children while crossing the Mediterranean to Greece. Four shirts, dipped in plaster and marked with a date of burial and location, hang above a Hebrew tombstone from the 1st-5th century C.E. Each shirt was worn by a Syrian child when they died on the coast of Greece–their names are unknown, and these were their sole earthly possessions. “Their clothing became their only home,” added Issam. He was alerted to these tragedies by a friend who was living in Greece at the time who helped him gather the shirts at burials before the clothing was discarded. With this act, he gives them their own tombstones. Their identity will always remain unknown, but their presence swallows the room.

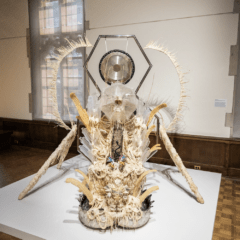

He uses burnt matches in two of his installations to represent refugees. Their charred tips are spent and fragile, but still intact. Crowded into miniature boats made from bicycle parts, their exodus of Biblical proportions occupies the middle of the exhibition inside a vitrine in “Dark Water, Burning World.” In “Seed,” a children’s doll is stuffed head first into a meat grinder. Rather than shredded cloth, a small mound of olive tree seeds sits below. As long as there is life there is hope, even if that life is trampled, bruised, and transient. A proverb on the wall reads “They tried to bury us–they didn’t know we were seeds.”

Issam Kourbaj is a Syrian-born artist currently residing in Cambridge, England. His work has been exhibited widely across the globe.

Cultures in the Crossfire: Stories from Iraq and Syria is on display at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology through through November 26, 2018. To read more about the important efforts the museum and the Penn Cultural Heritage Center are undertaking to document and protect Syrian and Iraqi cultural heritage visit the Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria and Iraq Project (SHOSI) website.