The art world is a good place to trace how wealth, power, beauty and even knowledge wither in the onslaught of death. The 16th century Christians of Flanders and Holland explored the notion of Vanitas, and their paintings and sculptures characterized the hunt for riches with caution: “All is vanity and chasing the wind.” [Eccl. 1:2, 14]. Christians 500 years ago suggested the real search ought to be how to live in the face of the pointlessness of existence, and artists almost everywhere, concurred.

Memento mori, Latin for the gentle reminder that “you must die,” are art works signified by the presence of the human skull. Indeed, artists throughout the ages have been obsessed with death. Cave drawings of flesh-eating animals, paintings of a dying Christ on the cross, dragon slaying, battle panoramas and contemporary fascination with skulls, bones and blood litter galleries and museums. Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533), the artist’s most well known painting, features a distorted skull – though a right side viewing of the work corrects the distortion. Its presence in the midst of this double portrait of worldly nobles is a nod to the fleeting nature of life and the distortion, perhaps the shifting perception of reality.

Turn of the Century Painting

Still Life with Skull (1898) by French post-impressionist Paul Cezanne, in a number of still lifes, treats the skull less as a symbol of death than as another round fruit. Color modulations and a plastic sense of space serve as a dress rehearsal for the Cubism that would soon catch fire across the European art world. Known more for his apples, oranges, card players and views of Mont Sainte-Victoire than the human brainpan, Cezanne produced a handful of works featuring the skull. His Pyramid of Skulls (1901) consists of four stacked skulls, but again, the painting seems more technical than personal, considering his own death in 1906 was a mere five years away. [Note bene: In French “still life” translates to “nature morte,” or dead nature.]

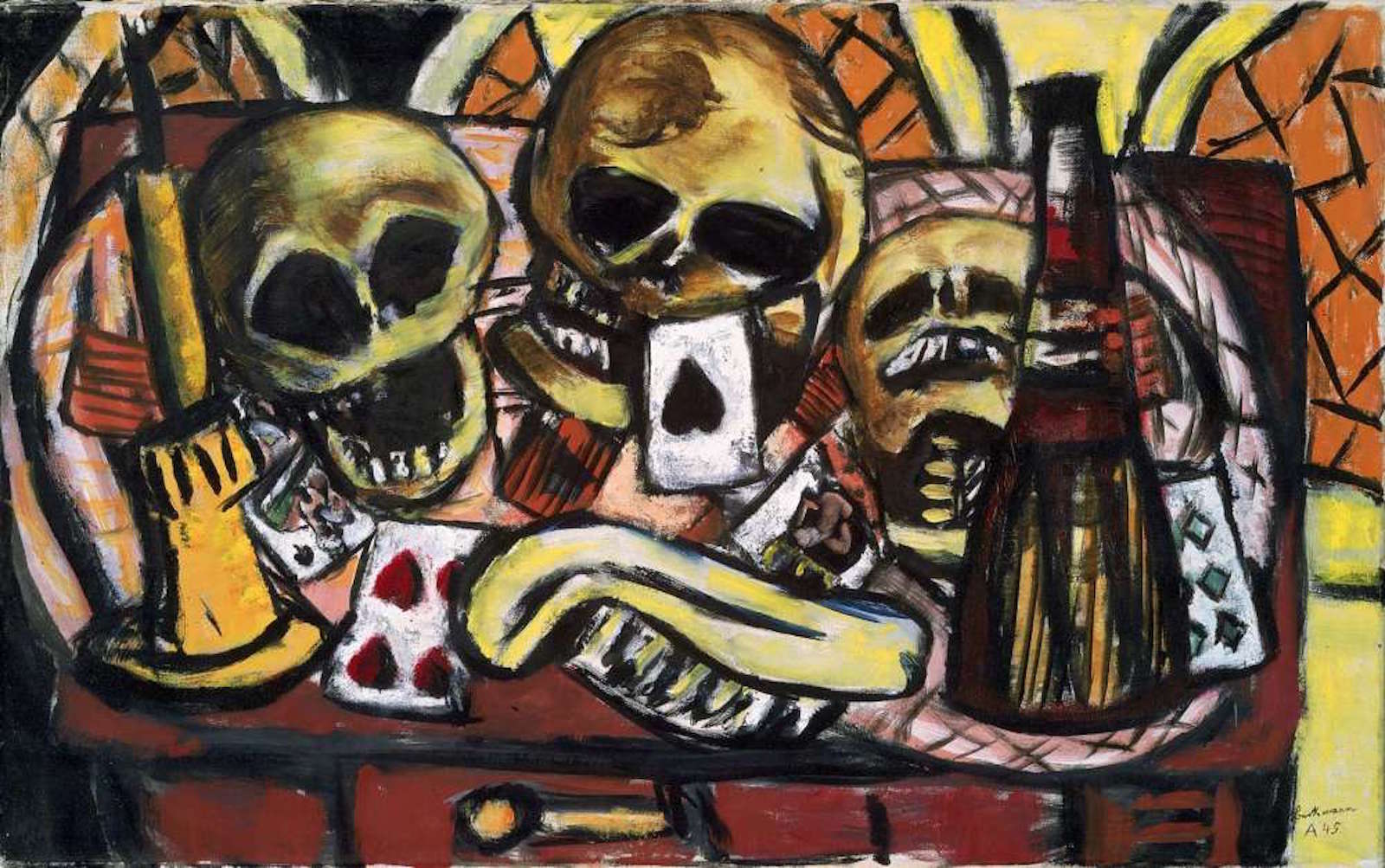

Max Beckmann’s Still Life with Three Skulls (1945) is more of a damning paean to the death culture of Nazi Germany than a reminder of the artist’s own death. The artist had fled Germany in 1937 for Amsterdam and the thick black outlines round the trio of cartoonish skulls, playing cards and an extinguished candle on a table echo a darkness war refugees fully understand. According to The Museum of Fine Art in Boston where this work hangs, the still life was produced during the final months of World War II. Beckmann said it was “a truly grotesque time, full to the brim with work, Nazi persecutions, bombs, hunger.”

While not a painter of human skulls, Georgia O’Keefe lavished enormous amounts of attention on the sun-dried skulls of dead steer she found while working in the American Southwest. She did one work, however in 1943 – Head with Broken Pot. That painting post-dates a photograph of the artist with a human skull, taken in New Mexico in 1942. In any case, only a few years prior, O’Keefe painted some of the most sexualized flowers in art history.

The Prevalence of Skull Symbolism Today

Many of the skull images we encounter these days are often cartoons, drawings or human anatomical studies. Dread, fear and trembling seem to have yielded to irony, humor and song. Skulls with smoldering cigarettes or engaging in animated conversation are the food of slapstick and carnivals, and often obliquely tease out Hamlet’s doleful soliloquy on mortality as he holds a skull in a graveyard … “Alas poor Yorick…” The Grateful Dead’s skull-and-rose-laurels logo, designed by Alton Kelley and Stanley “Mouse” Miller, is typical of contemporary nods to the fact of our death, and the image has been plastered joyfully on millions of albums, stickers and t-shirts.

In fact, a Halloween quality pervades the contemporary skeleton and the skull imagery. The rise of a post-war middle class and television has likely fueled a culture of irony and dark humor. For example, Hells Angels motorcycle members brandish helmets sporting skulls and angel wings; chainsaw-wielding zombie horror films are wildly popular; heavy metal rock bands bathe in skull imagery; even kids flying the pirates’ skull and crossbones (the Jolly Roger) all signal rebellion against life, against death. Criminals often wear skull rings, tattoos or clothing to show off their attraction to death, and remind us (and themselves) of their fearlessness. Prison tattooing is undoubtedly skull heavy, and the price for a needle and an inking is not more than a few cigarettes or stamps.

The deep desire to join some kind of death cult or to consume fear in the form of art, film, music or books is the not so subtle reminder that we will die. Married to skull imagery, it’s a valuable, if fractured, franchise. But contemporary art is where the real money is in the skull business.

American Artists

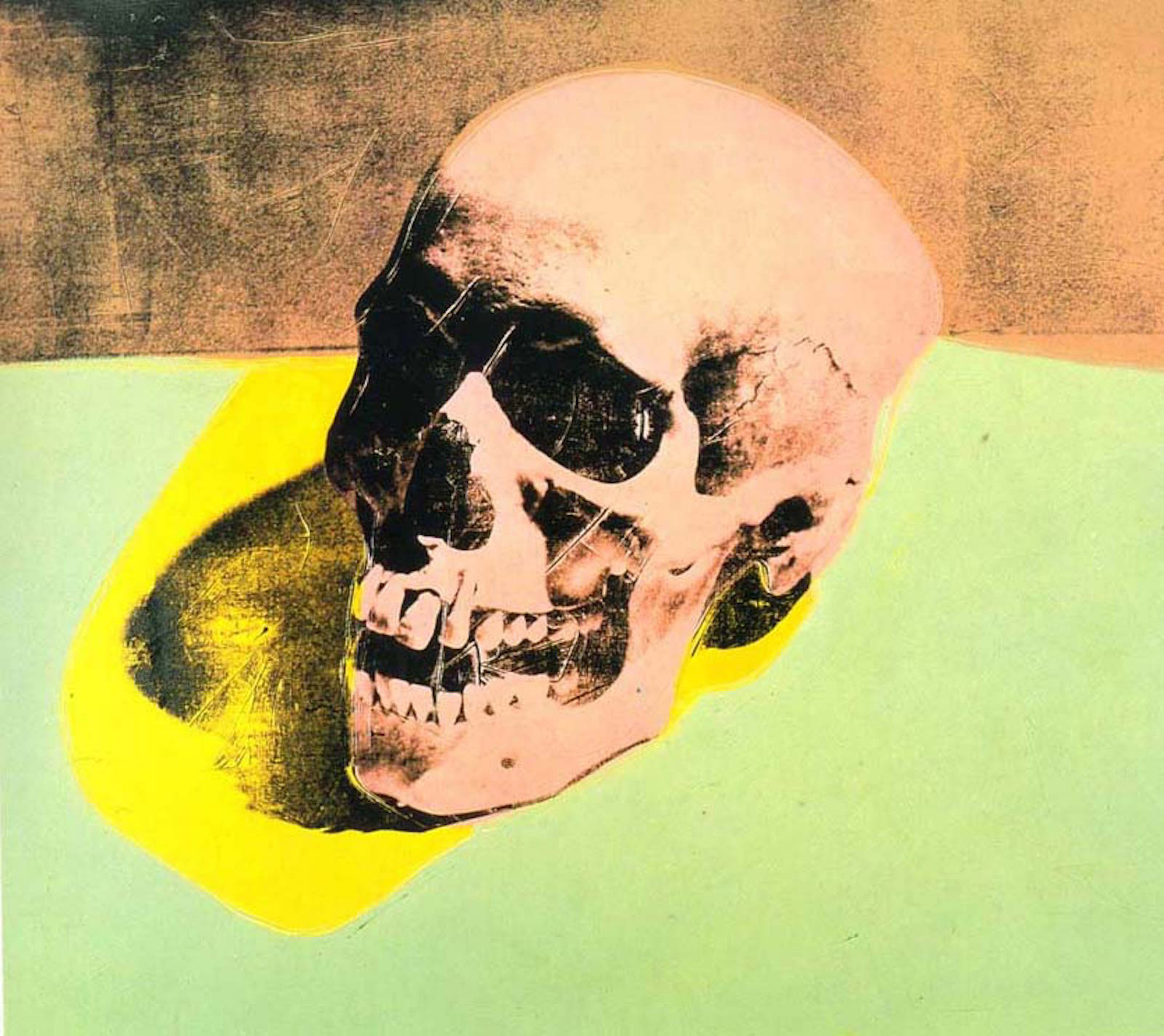

Andy Warhol’s dance with death, documented over a lifetime of car crashes, electric chairs, dead celebrities and just plain old death finally arrived with the classic memento mori, Skulls (1976). The group of silkscreened skulls stands at the other end of the spectrum of his production, if you began with his Flowers (1964), a silkscreened grid of hibiscus blossoms, pinched from a photo by Patricia Caulfield (she sued for a cash settlement). Out of fear of being sued again, Warhol then began taking his own photos and Skulls is one of those resulting works. The irony of Warhol’s Skulls is multi-layered, as the pop artist was often blamed for killing painting; was shot and nearly assassinated by groupie Valerie Solanas on June 3, 1968; and was a stoic witness to the slow declines and deaths of several of his superstars, including the waifish model, Edie Sedgwick.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose flame was bright but brief, lit up the New York art world in the 1980s, first with his graffiti works under the pseudonym SAMO, then as himself, a Haitian-Puerto Rican New York outsider who not only stimulated the oil-on-canvas set to get painting but also collectors and critics to spend money and time on the neo-expressionist rage. Basquiat painted hundreds of skulls that rapidly became a cottage industry fatally drenched, as it turned out, in heroin. Not long after Andy Warhol befriended him, Basquiat succumbed to his demons and overdosed in his Downtown NYC studio at the age of 27, leaving as it were, a beautiful corpse. His Untitled (1982), an immense black skull painted on canvas in oil and oil stick, broke records in May, 2017 as the most expensive work of art sold by an American artist. The gavel came down at $110.5 million (including fees) at Sotheby’s New York with Japanese e-commerce billionaire Yusaku Maezawa taking home the prize with plans to show it in his soon-to-be-built museum in Chiba, Japan. It appears that in retail, sex sells, and in the art world death does quite handsomely.

Contemporary Sculpture

Self (1991), by British artist Marc Quinn might be the only skull that is not a skull. The frozen replica of the artist’s head produced from 10 pints of his own blood is a vanitas extraordinaire. Kept frozen in a glass box, Self is both a shroud and a self-portrait. And Quinn, an odd archivist and collector himself, reexamines his head every five years, drawing another 10 pints of blood and turning on a deep freezer to house a new “self” portrait.

“This series of sculptures presents a cumulative index of passing time and an ongoing self-portrait of the artist’s aging and changing self,” says Quinn’s website of his “selves.”

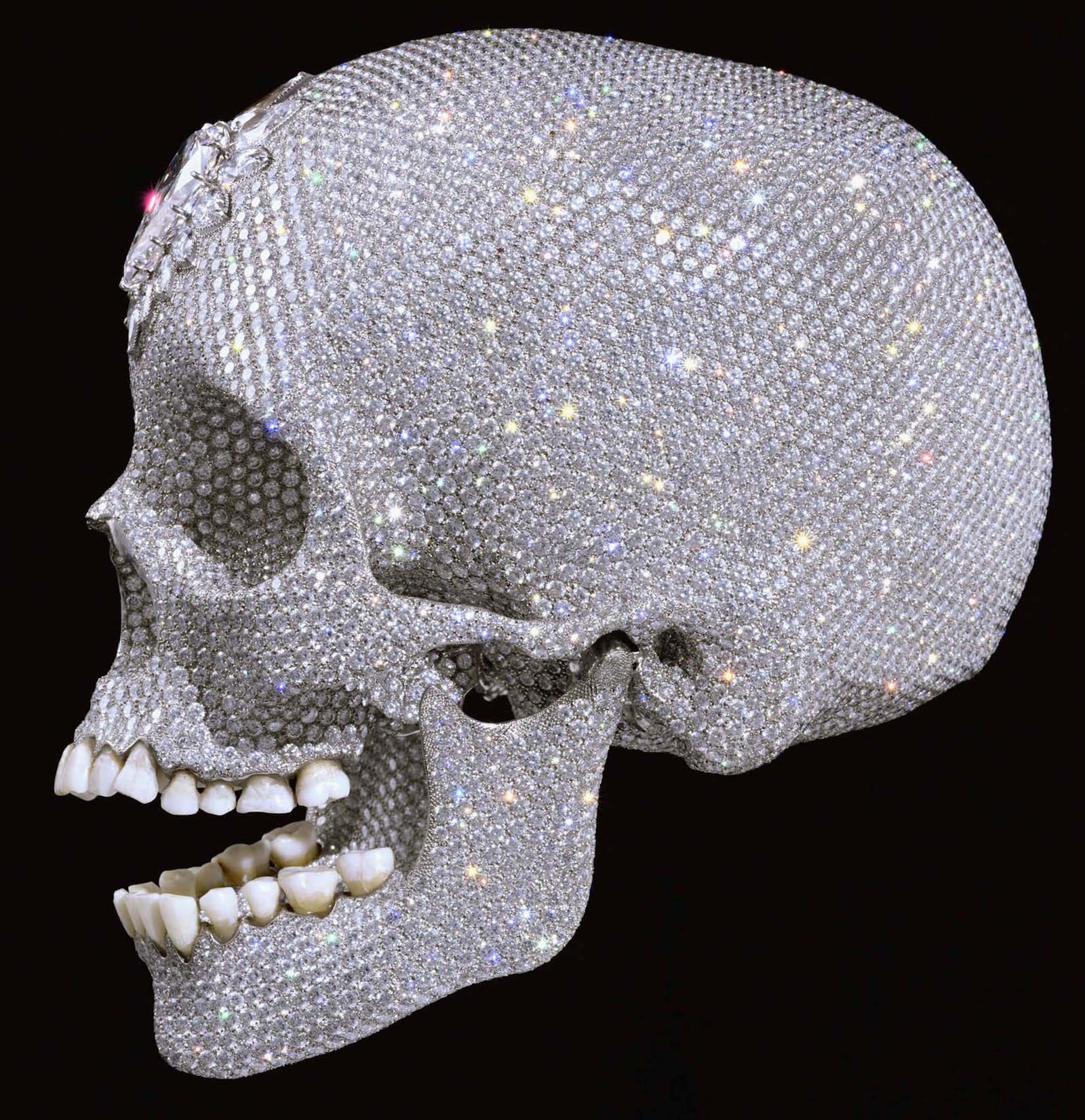

While not his own skull, Damien Hirst’s diamond-studded cranium For the Love of God (2007), was purported to be worth upwards of 50 million pounds. That is at least what the opening sales price was for this high-end memento mori. Covered with platinum, outfitted with human teeth, and plastered from chin to crown with 8,601 diamonds, Hirst’s work weighs in at 1106.18 carats. The piece was reportedly created (via Hirst’s instructions) for a price of 14 million pounds. More recent speculation about For the Love of God is that it was purchased by a consortium of collections, the artist himself among them. It’s a curious proposition and Hirst’s vanity ultimately and cynically begs the question “What price me?”

The Catacombs of Paris, France

Monetizing death and its coterie of object-symbols is clearly a booming business, particularly in Paris where hardly a tourist passes through The City of Light without a walk through one of its darkest passages. Père Lachaise, Le Cimetière du Montparnasse or Le Cimetière du Montmartre are large, gorgeous cemeteries but they are nearly beyond burial capacity. When walls collapsed at Les Innocents, the oldest and largest cemetery in Paris, in the late 1780s, the powers that be began delivering some millions of dead to the underground alabaster quarries beneath the Paris streets. The process begun in 1786 and mostly finished in 1788, created the largest underground grave in the world.

The Catacombs opened to the public in 1874 as a tourist attraction, and is now home to more than six million dead, their skulls and bones all stacked up neatly along a 1.5 kilometer trek some 17 meters underground in a chilled labyrinth of tunnels, at a stable 14 degrees celsius. While well lit and clean of trash and cigarette butts one finds above ground, there is a gruesome air in this exposed graveyard, but the several thousand tourists who hike through the dank ossuary each day find it all quite thrilling.

What is particularly striking is the ascent back to the here and now: A spiral staircase delivers you into the open arms of the Catacombs’ Gift Shop. Here a catalog of take-home souvenirs like the hand-sized skull soap, skull drinking mugs and shot glasses, skull magnets, skull tote bags (I SKULL PARIS), as well as skull-emblazoned caps and, of course, flash lights and knives (but no guns, sorry) all with skull logos on them. On the high-end of the skull souvenir price scale are crocheted craniums from South America (each 185 euros, including tax). And while not really a skull or ostensibly about death, a Catacombs candy counter offers tourists the chance to load Snickers and Twix bars into their own skulls. Alas, Death never tasted so sweet!