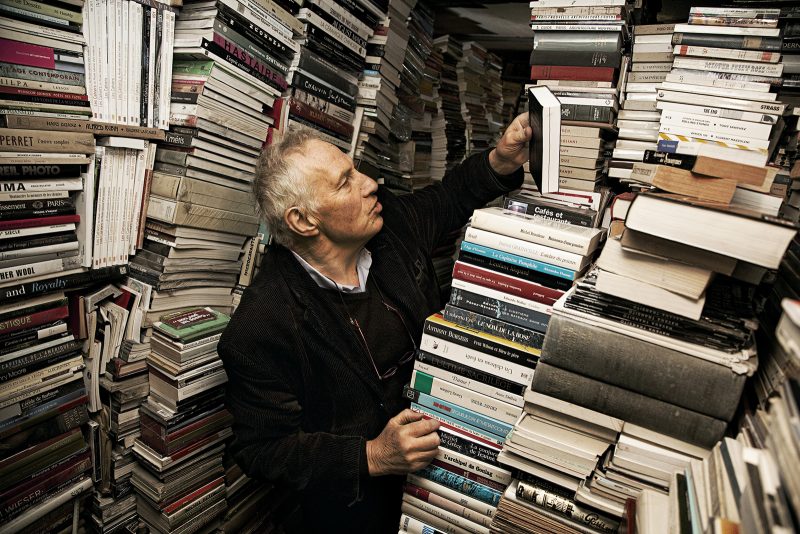

It wasn’t always like this. It wasn’t that long ago, back in the 80s, that you could actually walk inside Alias, his fine art bookstore. But then Léo began stacking the books vertically. And the stacks multiplied…more books came in than went out. From the outside, the columns of books appeared to hold up the ceiling, a sculptural art brut made by a bibliophile.

By the beginning of 2017, Léo had created – consciously or not – a monument, an installation, or perhaps a kind of Eden taking a page from Jorge-Luis Borges : “I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.”

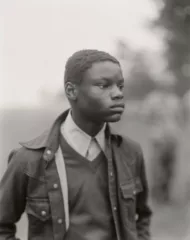

Jacques Léobold (Léo), who died in Paris at the age of 76 in early October, spent the better part of his adult life amassing one of the largest collections of books on Surrealism, Dada, Fluxus, Contemporary and Modern art in all flavors – French, English, German, Italian among other languages – in an old potato store at 21 Rue Boulard in the 14th arrondissement in Paris. Like paper skyscrapers, the book pillars went back as far as the eye could see taking up nearly all of the room’s 50-square meters, and leaving about one meter for Léo, master of this book-universe, to hold court and mind his brand of art brut.

“I don’t have anymore room,” Léo said when I asked what he was doing with all those books. “So, I’m obliged to make an artwork.”

In true Borgesian fashion, Léo’s librarie –Alias– became an ark of unreadable, labyrinthine knowledge. The 30,000-plus books were snaked and trapped between each other. You couldn’t remove one without the whole business coming down. Alias wasn’t retail; it was, alas, wholesale addiction. By the end of 2017, both Léo and his Alias were no more.

Léo was a friend and neighbor, a quirky personality whose insatiable hoarding was a local phenomenon. I bought inexpensive 1950s illustration books from him to make my collage works; once he bought some signed books from me. Sometimes he gave me books he didn’t want. In front of the store, there was always a box tucked beneath a plywood sawhorse table offering somewhat destroyed books for free. “Take them,” he would say. He always wore a rumpled jacket, his glasses always hanging round his neck on a string. Grumpy but lovable, Léo called me “Rose.”

Paris Landmark

Like Shakespeare & Company, Alias was one of those literary landmarks known for its owner as well as its ambiance and collection, which was chaos incarnate.

Léo, like Shakespeare & Co’s erudite curmudgeon, George Whitman, sat on a throne of sorts – Léo on a round, wooden stool and George, who died in 2011 at age 98, in a triangular cockpit that doubled as a check-out counter. And there, George would meticulously stamp any purchased book with the Shakespeare & Company logo. Léo’s take on the bookstore trade, however, was quite different. It was nearly impossible to buy any of his books, save for stuff stockpiled outside the store, let alone get a rubber stamp memento on the inside cover.

Any promise Léo made to dig out a specific title from his cavern was more like the dream of recovering laundry in a tornado. I once took the UK book and ephemera collector Paul Robertson to see Léo and Alias. Paul was looking for French surrealist material.

“Ah oui, bien sûr… “ Léo said. “Yes, I have things like that, but you don’t want me to get that for you now do you? Maybe come back next Wednesday….”

Of course selling books, for Léo, was not really the point of the store, but he would host occasional artist book signings. A dozen people showed up once when French performance artist Orlan checked in to sign her new catalogues. She stood outside the bookshop with a glass of wine holding court with a small cloud of artist and writer friends. But even though Léo had adventures in the New York book world, and made limited edition lithographs with his artist friends, he rarely talked to me about art, exhibitions, movements or even paint, but I suspected he knew quite a bit.

Léo’s books eventually spilled out onto the street – cheap paperback novels, foreign language dictionaries, catalogs, and miles of once-read magazines heaped up on rolling carts and sawhorse tables. As Léo got older, and sicker, the carts that were once rolled into the store at night (I often helped him push them up a ramp) stayed outside, covered with tarp and over the years the cart legs slowly sunk into the asphalt sidewalk.

With paint flaking off the façade, the building most probably unstable, was slated for either demolition or a complete overhaul; Léo’s lease would not be renewed. The restaurant next door, Au Vin des Rues, had already closed a year ago and quickly became a go-to wall for film and circus posters and xeroxed flyers for yoga classes and lost cats and the upper floors at 21 rue Boulard were long empty, some windows broken. To all of us in the neighborhood or to the eager tourist-bookworm, it was clear that trouble was afoot.

Then in early 2017 the books began to move out of Alias. When I passed Léo in the street or at Alias, I noticed he was thinner, gaunt. I realized he was sick. When the tons of books were gone and the store empty save scraps of exhibition posters from the 1960s and the odd turn of the century guide to French painting, Léo took to l’hopital St Joseph nearby. Within a week he was gone, too.

Paper Jewels

“You cannot help but find something interesting,” said Marc, an artist I met scanning the stalls in front of Alias, at a time when Leo was still healthy. Marc designed paperworks and invitations for the NYC gourmet shop Sherry-Lehman. “Each time I pass by, I stop to look. There are little things which interest me.”

That day Marc pulled out three picture postcards celebrating small French town centers. The cards were swimming in a large cardboard box with a thousand nearly identical images. After he bought them, he went to fetch a bottle of Bordeaux, some bread and cheese for himself and Leo – and anyone else who happened by.

I will miss the signs Léo’s taped to the door to his shop, particularly the one that read: “Never open before 11 am!” Another, pinned to a wall inside cautioned: “Entrée Interdite! Fouilles Archeologique!” (Do Not Enter! Archeological Site!). Now that the store is closed, a graffiti artist paid homage to Léo with a few telling drawings on the windows.

It’s not entirely true that Léo didn’t sell books and in fact, there were some vague plans according to friends of Léo’s wife Sylva, to sell the entire lot of books now in storage somewhere outside of Paris, and create an Alias library in Brittany or Lyon.

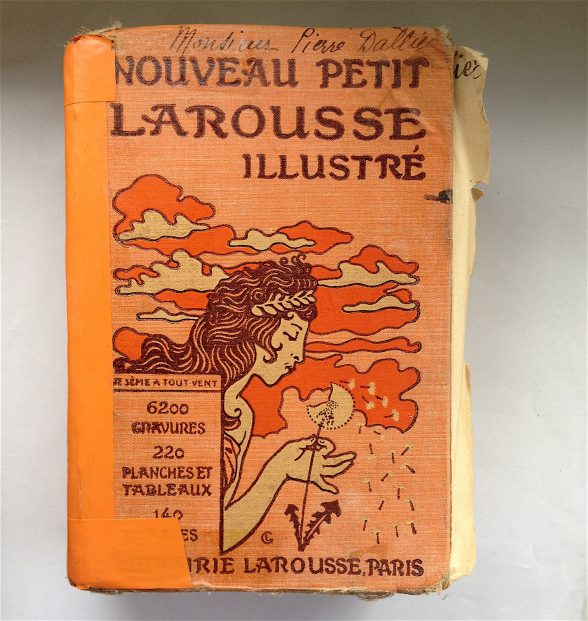

But you could (and I did) come across infinitely valuable treasures, a stack of Marie Claire magazines from the 1930s (which I covet), or a 1928 copy of the Nouveau Petit Larousse Illustré, a volume that covers the world from A to Z in only 1754 pages. Sadly, there is no entry in the the little Larousse for “alias.”

For more on Alias and Léo and a handful of photographs of the bookstore, please see Barbara Cyrille’s encounter.

Photos are by Victor Matussière, with permission. For more work, see his website.