Though the Louvre was the most visited museum in the world with 9.3 million people (in 2015), that number fell about 15% to about 7.4 million – a loss of about 10 million euros this past year, according to the UK Guardian. The Guardian goes on to explain the main culprit for the drop in attendance is terrorism, or the fear of it. But Paris is nothing if not a collection of museums that are the lifeblood of the city in a city that is itself a museum. So while it could be just be me, I’ve noticed an uptick in advertising for museum exhibitions where Parisians continue to gather: Underground.

Visual real estate with lots of eyeballs on it

After the Moscow Subway, the Métro is the largest public transport people mover in Europe. In 2014, more than 1.52 billion riders swung through the network of under- and overground trains that snake through Paris, according to the Brussels-based International Association of Public Transport. Some four million people pass through each of 303 Paris Métro stations every day. That’s a lot of eyes on an enormous amount of visual real estate below the street. And a constant opportunity to promote museums and the art they show with large, compelling posters that still work in attracting your attention, even if you’re plugged into Spotify on your iPhone.

A little history of the art poster

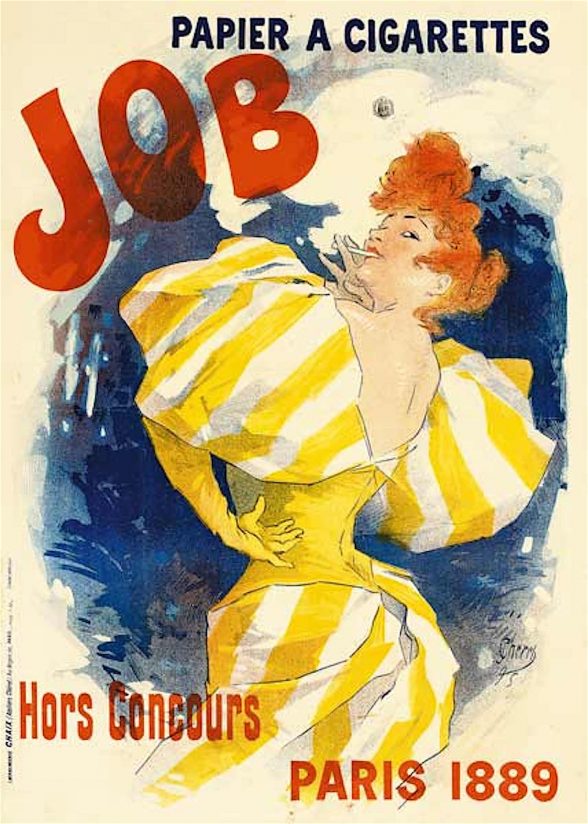

While they are merely copies, these massive Métro posters are vibrant treasures hidden in plain sight. And no secret, the poster itself, a 19th century advertising medium was largely created by French artist Jules Cheret.

The Frenchman’s use of a three-stone lithography process in the 1880s was a breakthrough that allowed artists to reproduce vibrant colors using only three inked stones – red, yellow and blue. Cheret went on to become a master of the poster and known – like fellow Frenchman Toulouse Lautrec – for his spirited and liberated images of women dancing and laughing and generally having a good time. Women in art were often viewed largely as prostitutes, according to Charet’s biography; the artist was called “The Father of the Women’s Liberation.”

The poster accelerated the dissemination of both word and image, particularly in cities where bourgeois middle class culture was flourishing, as in Paris at the end of the 19th century. At around the same time public transport like the Métro was launched city-wide. The Métro’s first line opened in 1900 during the “Exposition Universel,” The Paris World’s Fair. It’s not hard to see how these two technologies came together over the last 100 years to promote and advance culture.

A roundup of posters now available in the Paris Metro

So while it is impossible to see all the shows in the 130 museums around Paris, a person is able to glimpse a cornucopia of exhibitions this fall – riding on the Métro. The David Hockney show that just ended at The Pompidou, featured an unmissable “Big Splash” plastered across the Métro system. The Musée Maillol’s Whitney’s Pop Art Show (Icons that Matter) caught my attention with Roy Lichtenstein’s 1963 “Girl in Window (Study for World’s Fair Mural)” giggling a “Hello!” from an open window.

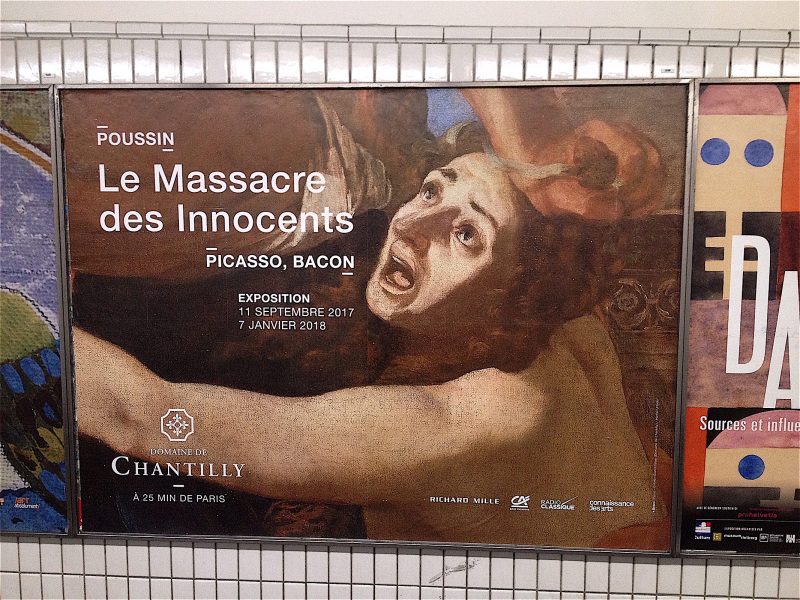

An exhibition on the theme of “Le Massacre des Innocents” (The Massacre of the Innocents, 1627-1628), at the Domaine de Chantilly (25 minutes from Paris) brings together three giants, Nicholas Poussin, Picasso and Francis Bacon. On the poster, though, a cropping of Poussin’s powerful painting shows only a parent begging a soldier to stop the carnage – to save a child King Herod had ordered executed.

My guess is that the full image of the soldier with his foot stamping the infant’s neck, sword poised to kill, would have been too violent and unsettling for Parisians who endured a handful of senseless killings over the past few years.

The La Bibliothèque Nationale de France launched an exhibition of photographs of French Paysages (landscapes) with compelling full on images promoting the exhibition. Alban Lécuyer’s photo of people watching a controlled explosion of a house in Nantes stopped quite a few people as they moved through one Métro station.

Some of these advertisements are to be found on the street close to the Métro entrances as well. The new and beautiful Fondation Louis Vuitton designed by American architect Frank Gehry, installed “MoMA’s Etre Monderne” (To Be Modern), and promoted the show with large, beautiful posters under glass along many Paris boulevards.

Contemplating contemporary and modern art for ten minutes

Clearly the underground context of the Métro permits a different kind of looking with a different set of aesthetic situations. In New York City in the late 1970s and early 1980s, black, papered-over ad spaces offered a young Keith Haring a unique space to invent his own iconography – in white chalk – of radiating babies, dancing-barking dogs and spaceships. Other graffiti artists have altered existing ad posters, reinventing a narrative for Mad Men tv soap’s “falling man” by adding an alligator’s open jaws, Superman zooming in or a woman’s behind to catch him.

Underground art in Paris seems to mostly encourage Parisians to contemplate contemporary and modern art, absent the interventions and alterations. There’s a bit of pleasure absorbing the cultural heartbeat of the city in about the 10 minutes it takes to ride from the left to the right bank. And perhaps considering, for example, Jean-François Millet’s dirt farmer “Man with a Hoe” (1862), and a much simpler 19th century life.

[Ed Note: Want more about art posters in transit? See the recent NYT article about censorship of an Egon Schiele poster in the London Underground.]