“One should not only photograph things for what they are, but for what else they are.”

– Minor White

The 2015 documentary, An Art That Nature Makes, about the long, distinguished career of the photographer Rosamond Purcell, envelopes you for an intense 75 minutes in the artist’s story and her majestic, lyrical images of the discarded, the rejected, the ignored, the weird, the unheralded. As the filmmaker Errol Morris notes in the film, Purcell captures “the history of objects by photographing them in romantic decline.”

In this short, engaging film, we see Purcell’s life as a practicing artist, digging through a junkyard to find her unique discoveries and setting up her close-angle shots of animal skeletons and specimens — some of them staged on the roof of the Academy of Natural Sciences — a single bird wing, decomposing books and other human industrial discards, now artifacts. We see her philosophize about art and science and natural history, and about the idea of wonder, and hear her eloquently describe the thinking that underlies her work, and the processes she has employed to realize her visions. A Boston-born and Boston-rooted artist, the daughter of a Harvard historian, Purcell’s career was inaugurated by visits to Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and by the gift of a camera.

Owls Head Antique Shop and junkyard treasures

The documentary, directed by Molly Bernstein, begins and ends at William Buckminster’s Owls Head Antique Shop, near Rockland, Maine. Owls Head was a multi-acre, colossal junk yard, which Purcell frequented and photographed for decades, and from which she acquired a large collection of objects which she incorporated into her work. Owls Head exists no longer, but the treasures that Purcell discovered there and displayed in her studio live on in her work.

Purcell does far more than record the disintegration of objects and forms of life. She is a curator of objects – from relics discovered in the dregs of Owls Head to oddities encountered in the archives of science and natural history museums. She is a poet of object management. In one of her well known images, Purcell has arranged eight small monkey specimens in two rows, with their arms raised to the sky, their mouths agape and stuffed with white cotton and with glowing white eyes, and in the film she notes that it is as if they were a crowd of medieval people about to be struck by a meteorite.

Cellulose nitrate dice

In the 19th century, and until the middle of the 20th century, dice were made from cellulose nitrate, an unstable, indeed explosive, compound, which decays over time. Ricky Jay, an American illusionist and actor, and author of an offbeat history of the die, Dice: Deception, Fate & Rotten Luck, had a collection of them which Purcell photographed, preserving something of their essence in gloriously beautiful color and texture.

Common Murre eggs

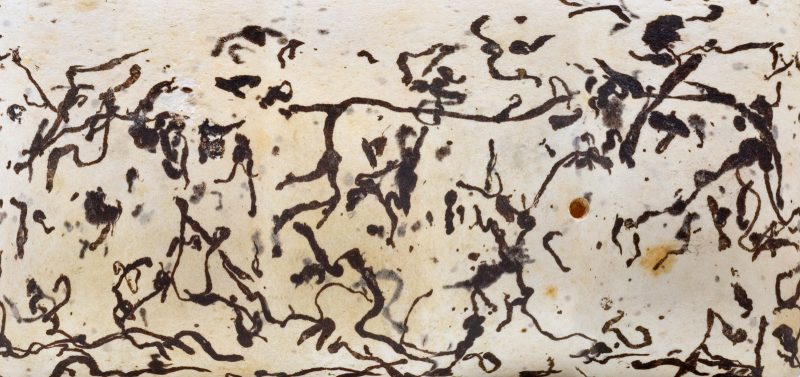

An Art That Nature Makes chronicles Purcell’s longstanding interest in the meeting of art and science, with, for example, a trip she took to the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology in Camarillo, California, where she photographed its collection of Common Murre eggs, some of them 100 years old. These incredible specimens, which were found on Arctic coastal cliffs, each display unique, patterned, inky markings on the surface, which allows the eggs to be identified by their mothers. Purcell was enchanted by these eggs, photographed them from all angles, and with her husband, Dennis Purcell, created panorama prints of them reminiscent of “Mercator” projections. The compositions look like works of modern abstract art. Indeed, their similarity to work by the likes of Francis Bacon, Cy Twombly and Jackson Pollock is striking.

Purcell’s “Museum Wormianum” and other oddities

Purcell likes to photograph in natural light, on window sills, on the roofs of museums. She likes to arrange things. She is an orchestrator, a collagist. Her work often incorporates shadows and unexpected backgrounds. She flirts with the illusory, with camouflage, with ambiguity. She likes to focus upon portions of things, elements of a whole. What might in other hands seem contrived, in Purcell’s seems poetic, and often painterly.

The photographs Purcell creates are often as disturbing as they are astonishing. The film highlights many of them – from the preserved hydrocephalic head of child which somehow looks like an opened tulip, to Peter the Great’s collection of molars, to a tree branch grown around the skeleton of the lower jaw of a horse, to an old book turned into a nest by squirrels or mice, to the preserved skeletons of conjoined twins.

Unsurprisingly, Purcell has worked with the Mütter Museum — its collection of human anomalies a perfect match for her interest in what she has called “special cases.” Through elegant, even lyrical imagery, she demystifies natural phenomena that may otherwise repel us, and she demonstrates that grace exists in the unexpected. I would call her the Diane Arbus of the natural world of photography.

Purcell also is a “wonder cabinet” maker, like Duchamp and Joseph Cornell, and is famous for her reproduction of Ole Worm’s 17th century cabinet of curiosities, his “Musei Wormiani Historia.” Purcell’s life-size reproduction of Worm’s room, titled, All things strange and beautiful, is now permanently installed at the Geological Museum at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

Purcell’s work has been exhibited widely. She has been a regular contributor to National Geographic magazine, and has published over twenty books, including A Glorious Enterprise: The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and the Making of American Science (with Robert McCracken Peck, the Academy’s Senior Fellow, who appears in the film and is scheduled to participate in its coming screening in Philadelphia, and Patricia Tyson Stoud); Crossing Over – Where Art and Science Meet (with the great paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould); Landscapes of the Passing Strange (with the Shakespeare scholar Michael Witmore — a photographic journey into the imaginative world of Shakespeare’s plays); and Owls Head: On the Nature of Lost Things.

An Art That Nature Makes was produced by Alan Edelstein, with Philip Dolan as executive producer. It premiered at the 2015 DOC NYC film festival. The film is now screening around the country. I learned about it from a friend who saw it in Amherst, Massachusetts. There will be a screening in Philadelphia at the Lightbox Film Center of the International House on March 8, 2018, with a discussion by the director and producer, and including, among others, Robert Peck.