VISITOR BEWARE

“Art is here to prove, and to help one bear, the fact that all safety is an illusion.” –James Baldwin

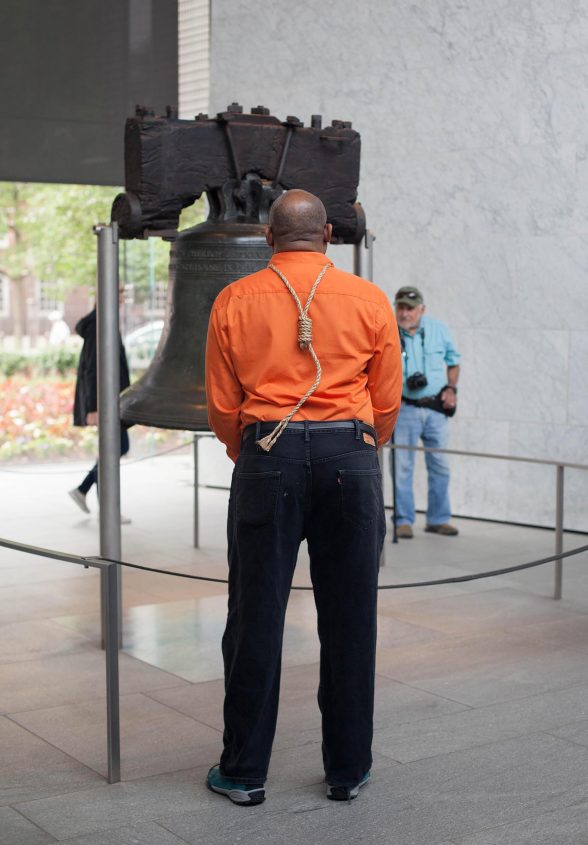

As you enter the African American Museum in Philadelphia to visit the museum’s summer 2018 group exhibition, Collective Conscious: The Art of Social Change, prepare yourself for Sherman Fleming’s chilling work — “Invisible n00se: Bearing Witness at the Liberty Bell #2.” In the photograph displayed, which documents a performance by the artist, a Black man stands before the Liberty Bell, his back to the camera. His head is shaved. He is wearing an orange shirt, the shade of prison coveralls. A noose is draped around his neck, like a necklace, but it rests on his back. There are tourists in the background, one a white man wearing a baseball cap, with a camera draped around his neck. You view the scene from behind the Black man as he ponders, perhaps questioning, this national symbol of liberty which, according to the inscription on the Bell, proclaims liberty for all of the inhabitants of the land.

The inscription, which is blocked in the photograph by the man’s body, actually reads: “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof.” It is a quote from Leviticus (25:10), a biblical reference to the historical slavery of Jews. Although the Liberty Bell dates back to our country’s independence, it was not until the early years of the nineteenth century that abolitionists, grasping the inescapable, tragic irony of the inscription in a land that had embraced slavery, appropriated it for their mission. In Mr. Fleming’s work, the Black man justly obstructs our view of the inscribed proclamation on behalf of people of color who have been, and continue to be, excluded, enslaved, condemned, even murdered in our country. (Ed. Note: Listen to 2016 podcast interview of Sherman Fleming, talking with his friend and Artblog correspondent, the late A.M. Weaver. https://www.theartblog.org/2016/12/sherman-fleming-talks-performance-and-black-masculinity-with-a-m-weaver/)

The noble mission of the abolitionists — that is, liberty for all — of course, continues today in certain quarters, and it is central to the powerful and disturbing and moving and often beautiful work of the eleven local artists of color in this exhibition, each of them grappling with their place in community, in history. Each of them presenting and preserving their narratives and impressions, which we honor with our recognition.

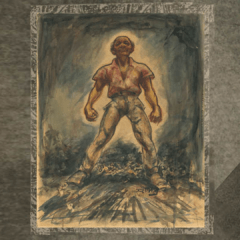

Canvas Rorschach Paintings of Russell Craig from the E-Val Series

A full room of the exhibition is devoted to a series of large canvases tacked to the walls, creations of Russell Craig, his “E-Val Series.” They are giant monochrome Rorschachs, but with the addition of eyes painted on that peer out at the viewer – so that the oversized, dark rust colored inkblots resemble faces. Sadly, they are intended to be the faces of girls and women of color who have been murdered by police in our country of LIBERTY. The paint Mr. Craig uses to make his point is the blood of cows — a substitute for human blood. The images are chilling.

Rorschachs, of course, are projective psychological tests which purport to determine whether a person’s thoughts are *normal.* Here, Craig rightfully turns the concept of normalcy on its head by portraying the suggested images of murder victims of color, killed by government authorities.

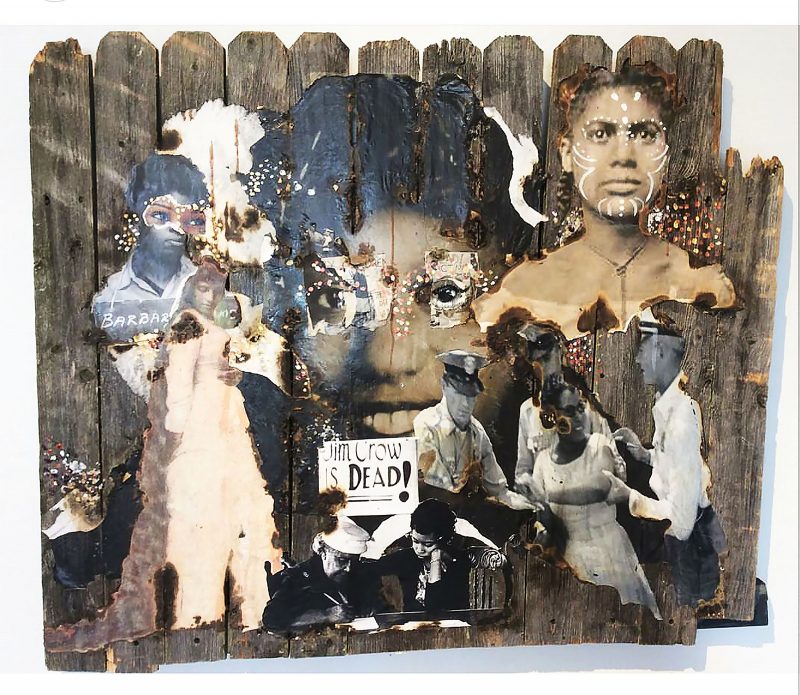

Fence Shrines — Lavett Ballard

Lavett Ballard creates fence shrines – narrative photographic installations on gritty picket fences she constructs — which honor and glorify the struggles and achievements of African Americans, and connect their stories to their lost, forgotten, or ignored African ancestry.

In Ballard’s “Stories my Grandmother Told me,” there appears another set of harrowing faces – again with the glare of their eyes directed to the viewer — of African American women gathered around a “Jim Crow is Dead!” sign, and with white policemen surrounding one of the Black women. Ballard layers, tears, and sometimes burns the images she presents, and adds African tribal markings to the photos of the faces, in addition to other adornments, in striking compositions which capture the challenges faced by the people she is portraying, connect their stories to their ancestry, and veneate them.

In this work, as in a number of her others included in the exhibition, the narrative is infected by the various legacies of slavery, exclusion, and harassment African Americans have experienced throughout the history of our country. The fences themselves beg the question (famously memorialized in another context by Robert Frost in “Mending Wall”) of whether the intention is to wall in or to wall out. In a country that remains highly segregated by race, in a political environment where building a border wall appeals to the basest and racist fears of many of our inhabitants, the questions Ballard’s work provoke are critically important.

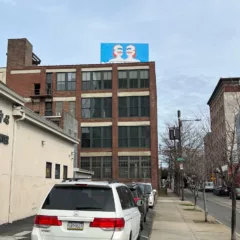

Joshua Graupera’s Mythological Blockadia

Mr. Graupera’s Blockadia project grew out the of slaying of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, and involves the organization of community events around the country designed to create “safe spaces” for people of color. Among other elements of the project, Collective Conscious: The Art of Social Change includes colorful signage which sets forth the manifesto of Blockadia —

“BLOCKADIA IS A SEPARATIST POLITICAL + CULTURAL LANDSCAPE DESIGNED as an INTERGALACTIC SAFE SPACE FOR PEOPLE OF COLOR – IT IS HERE FOR YOU TO GATHER LEARN + ORGANIZE TOGETHER. PLEASE TAKE CARE OF YOURSELF + EACH OTHER. THEN/WE CAN ALL SET WHITE SUPREMACY ON FIRE.”

I did not fully appreciate the symbolism of the “intergalactic” element of the project, which I gather involves portals that provide access to the “safe spaces” envisioned, and which then disappear. I did wonder whether this might relate to recent political seismic shifts which followed in the wake of events such as the shooting of Michael Brown, which generated hope but also profound disappointment. In any event, Graupera’s overarching message related to Afro Futurism — myth-building, community building, and community activism — is a powerful and important one.

The AAMP Residency for Art and Social Change

There is a great deal more to contemplate in Collective Conscious: The Art of Social Change, which has been curated by the museum’s Director of Curatorial Services, Dejay B. Duckett. The eleven artists featured in the exhibition include Diane Allen, Lavett Ballard, Russell Craig, Joshua Graupera, Keir Johnston, Nile Livingston, Sherman Fleming, Betty Leacraft, James Maurelle, Tieshka K. Smith, and Shawn Theodore – all nominees for the museum’s Residency for Art and Social Change. Russell Craig and Sherman Fleming were selected as this year’s residents.

The exhibition will be up at AAMP through August 26th.