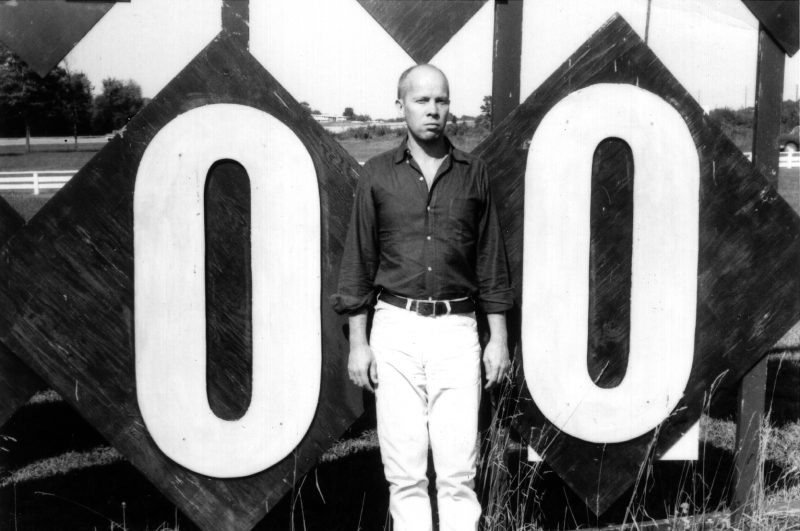

On Friday, 13 January, 1995 artist Ray Johnson launched himself from the Sag Harbor Bridge into the icy waters below and drowned — an apparent suicide. For an artist who spent his life communicating seemingly non-stop, his death left a mysterious and silent wake. Since that time, nearly a dozen books and one film (How to Draw a Bunny (2002)) have attempted to unravel not only his death, but Johnson’s intricate, layered collages, his unbridled “university” of mail art (The New York Correspondence School) and his always-on dead pan persona.

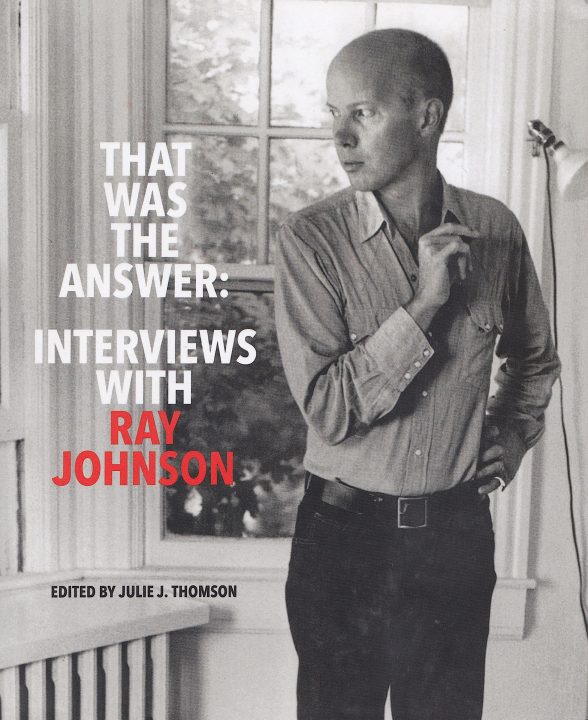

That Was The Answer: Interviews with Ray Johnson (2018) edited by Julie J. Thomson is the latest in a series of publications aiming to decipher Johnson’s art and life. Thomson “curates” a dozen interviews in which Johnson talks, often in a stream of consciousness, about himself, his art and his process — breathing life into his world.

Collages Built out of Conversation

Johnson’s brand of beautiful, merry-go-round explanations constitute the bulk of these conversations. His nonstop riffs on his creative process, dollops of art world gossip and whatever else floats in front of him, form vibrant, beautiful puzzles.

Here’s a bizarre story about bêche-de-mer (sea cucumber or sea worm), a dead raccoon presented to a fellow artist, taking a taxi from Barbara Bar to Harbor Bar, an Electrolux vacuum cleaner bag “brimming with dust, signed and dated for Andy Warhol,” foot-long hot dogs dropped from a helicopter, and chopped up artworks loaded with art world names.

Critic David Bourdon’s 1964 Artforum interview, the first in this collection, sets the tone as Johnson responds to questions in a casual, non-sequitur fashion:

Bourdon: I seldom see any collages that are fresher and more contemporary than Schwitters’s. I think it’s impossible to say you “work in the tradition of Schwitters,” because he indicated so clearly and exploited so fully the possibilities of collage. He is a terminal artist, a dead end. What future do you see in collage?

Johnson: Yes, I was born in Detroit in a log cabin and I attended Black Mountain Collage [sic] in North Carolina, where I once carried a log from the top of a mountain to the bottom of the mountain and threw it in a stream.

Show and Tell

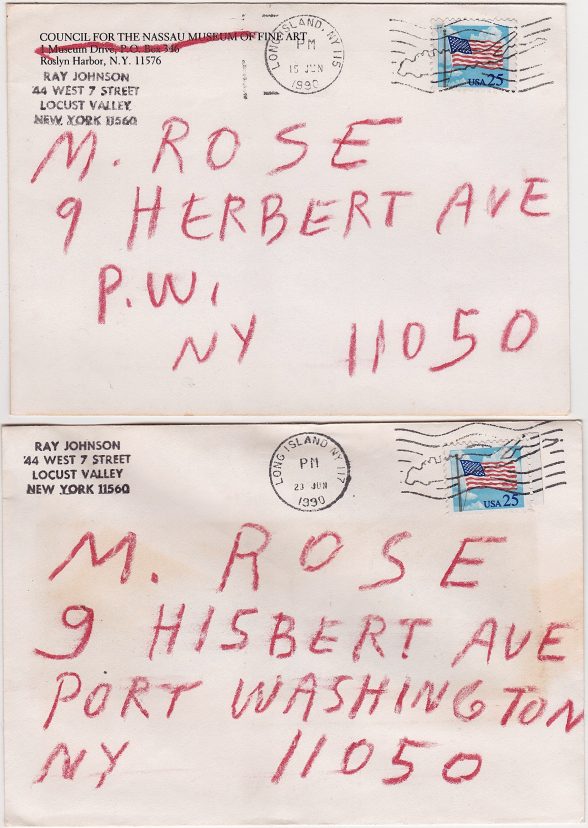

Though I met Ray Johnson in June, 1990 at my Port Washington, Long Island apartment, and corresponded with him over the years, I never stepped inside his house in Locust Valley New York, only 15 minutes away. So I was eager to reread Richard Bernstein’s piece on his visit to Johnson’s house in Locust Valley, New York, published in Andy Warhol’s Interview, “Ray Johnson’s World” (August 1972). Here, Johnson is in full show and tell mode on his most intimate stage – his home.

Upon entering Johnson’s house, Bernstein notices a “silvery white huge crepe of an acrylic paint puddle dried right into an oriental rug forever.” Johnson deadpans: “Oh, that’s a can of paint kicked over by the ghost of Janis Joplin.” Thomson’s book is loaded with these gems.

Henry Martin’s “Should an eyelash last forever?” in the 1984 Lotta Poetica 2, offers a rich and elucidating back and forth prefaced by Johnson’s history as both collage master and creator and “director” of The New York Correspondence School, an expansive collection of people who exchanged ‘add to” and “send to” art works typically by mail, with each other and Johnson himself.

Johnson explains his creative process on several occasions. He connects artist Frederick Kiesler’s “The Birth of a Lake” to the difficulty some native Japanese speakers have with pronouncing “Ls” — transforming them into “Rs.” Associations, orthographic and phonetic inversions pile up — “The Rake’s Progress,” “Veronica “Rake,” “Sade in Japan/Made in Japan” — as Johnson adds other mind rhymes to the mix until he arrives at his 1982 collage “Birth of a Rake.”

“I’ll do a whole slew of these women with rakes giving birth to lakes and Veronica Rake’s Mother’s Potato Masher will be depicted,” Johnson tells Martin. “…and so you can see how the subject matter is just endless.”

Playing it Coy

John Held Jr., an archivist of contemporary art movements, speaks with Johnson at the Mid York Library System in Utica, New York, following one of Johnson’s performances. Held succeeds in eliciting a river of information about Johnson’s role with mail art, Fluxus, Dada and art world names as well as his process, but still, Johnson holds court unfurling ideas in real time – collages built out of conversation:

Held Jr.: I saw a Ray Johnson advertised to appear on The Johnny Carson Show one evening.

Johnson: Yes. Now my ideal is to be on The Johnny Carson Show with Ray Johnson. You’ll think it was a typographical error in the newspaper. Ray Johnson, comma Ray Johnson, Comma Charro. Whoever.

Held Jr.: I’d love to see that show.

Johnson’s idiosyncratic circular explications are a form of music, a kind of spoken “live poetry.” There is joy in the rhythm Johnson imbues in his language and ideas as he pole vaults poetically through these exchanges. What emerges from these Q & A portraits is a lyrical, artist-child fashioning a world with the fabric of chance. We hear Johnson thinking and working through ideas, witness his coyness as he pulls his interviewer (and us) down the rabbit hole and back up, through the flowery thicket of his mind and out to an expansive shore where he tosses paper airplanes into the sea.

Julie J. Thomson, ed., That Was The Answer: Interviews with Ray Johnson, Chicago, IL: Soberscove Press, 2018 (Soberscove, Amazon)