Through Mr. Mason, my middle school art teacher, discussing the Harlem Renaissance, I learned for the first time about the existence of Black visual artists, of a Black woman sculptor named Augusta Savage born Augusta Christine Fells (1892-1962). Curator Jeffreen Hayes has managed to increase the joy and wonder a thousandfold on the second floor of the New-York Historical Society bringing Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman from Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens in Jacksonville, Florida. Savage’s profound contributions to the art world as both creator and educator are intertwined together in two spacious galleries.

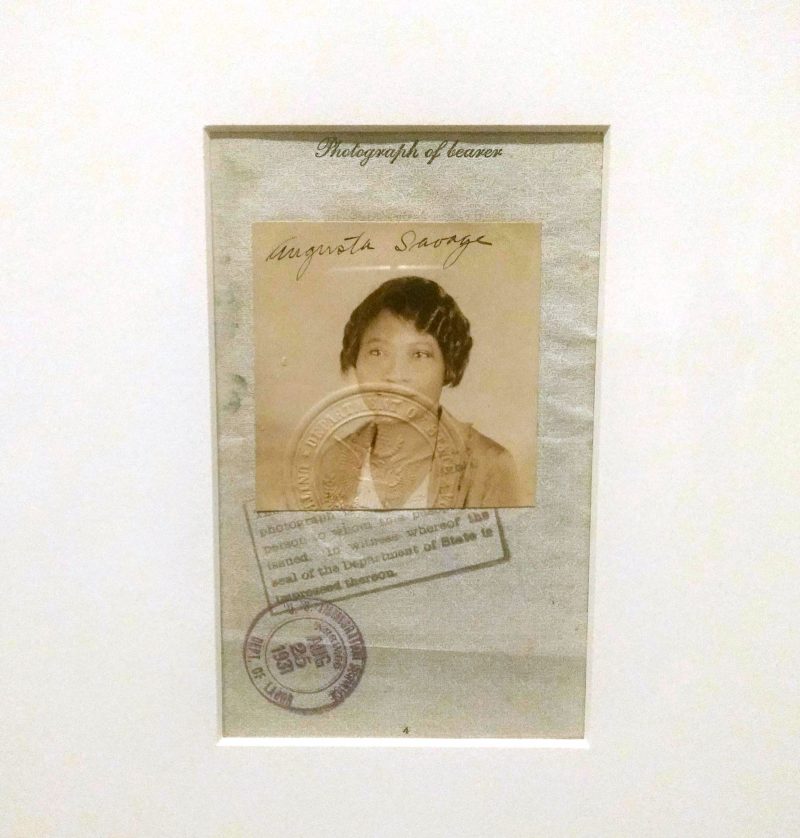

If anyone has ever researched Savage, rifling through her two archive boxes and the digital photograph database at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which happens to house the largest collection of Savage’s work, this exhibition carefully retrieves that information privileged to Savage scholars. The exhibit is a diligently constructed devotion to Savage, a rich, fascinating oeuvre that includes Savage’s sculpture, rarely seen watercolor, her passport, correspondence from Savage to W. E. B. DuBois, photographs, and works from her students Norman Lewis, Gwendolyn Knight, and Jacob Lawrence.

Savage was an incredibly gifted sculpturess, using clay early on and graduating onto plaster, bronze, and marble. In times of other Black women artists like Edmonia Lewis and Selma Burke, Savage created the most humanistic faces, bedazzling many Harlem Renaissance figures with her ability to convey expression. For example, “Untitled (Girl With Pigtails)” is a sophisticated bronze bust of small, intimate scale. The exquisite portrait– a soft, innocent face with long hair tied by two eloquent bows– is not an exaggerated caricature expected from Black artists of that particular period. The sweet, tender sincerity that Savage has captured in this adorable child signifies the importance of immortalizing her subjects realistically and emotively. It is especially imperative to note that bronze, a luxury material that was hard for Savage and other Black artists to acquire, places works like “Untitled (Girl With Pigtails)” in high esteem.

Savage, who loved building toys from mud as a child, committed a revolutionary act by disrupting the white male art infrastructure, accomplishing mastery that must have shocked many. She defeated the racial odds stacked against her, creating a defiant “John Henry.” This patinated plaster sculpture of a Black folk hero, with his large eyes, broad nose, and full lips, exemplifies that a poor Southern girl’s fascination for wet dirt was meant to materialize into her adulthood’s skill set in plaster, bronze, and marble.

“Reclining Nude,” possibly one of the first depictions of a Black woman nude, is carved in marble, showcasing Savage’s mastery range in sculpture. A sitting woman’s bob hairstyle covers her face, one arm is beneath her head, and her hand wraps around her stretched ankle. This smooth piece, interesting at all angles, with its fluid cuts and careful marks, reveals Savage’s appreciation for the figuration. Busts are seemingly her most celebrated, but Savage had commendable knowledge of the figure and that is felt in these two galleries.

Painted plaster, 91⁄4 x 6 x 4 in. Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, Florida, Purchased with funds from the Morton R. Hirschberg Bequest, AP.2013.1.1. Public domain in practice

In the second gallery, photographs of Savage’s community programs and successful openings– one with Savage posed with Eleanor Roosevelt. It was also incredible to see “Gamin” again, considered her most famous work, a third time, having first seen the bust of Savage’s young nephew included in Columbus Museum of Art’s I, Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance At 100 and Newark Museum’s Harlem Renaissance. “Gamin” is a bronze bust of a boy in newsboy cap, his eyes directed towards the side, dressed in a collar shirt. Again, her portraits have a quality that suggests affection for the sitter, love for the Black body sans stereotype.

This gallery also contains a high resolution image of Savage working on the larger version of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” with the smaller version posed in front. The sculpture commissioned for The World’s Fair is inspired by the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” with lyrics penned by James Weldon Johnson, whose bust by Savage is displayed nearby. Savage obviously worked long and hard on “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” putting forth a tremendous amount of love and labor. Unfortunately, this image, both heartbreaking and powerful, is the only way that we knew of this sculpture’s existence. After the fair was over, the monumental plaster work was destroyed due to Savage having no funds for casting or storage.

The intelligent Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman is certainly a long time coming. I spent an hour at the New-York Historical Society, reflecting on Savage’s work, recalling my fascinated thirteen-year-old self’s longing to learn more about this mysterious Black woman artist lacking a section in art history textbooks. This thoughtful exhibition allows one of Harlem’s most prominent women figures to have center stage. Her loud and clear voice articulated through various sculptural mediums will astonish visitors that know of her and those discovering someone new. Although Savage left behind a humble body of art, her significant contributions as an artist, writer, educator, and community leader cannot be ignored.

If only Mr. Mason were here today to see this euphoric exhibition, to know that my art hero, Augusta Savage, finally has a proper retrospective and that I was able to experience the sublime.

“Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman,” on view until July 28, 2019, New York Historical Society ,170 Central Park West at Richard Gilder Way (77th Street), New York, NY 10024. Open Tuesday through Thursday 10AM- 6PM, Friday 10AM-8PM, Saturday 10AM-6PM, and Sunday 11AM-5PM.