Nishat Hossain is a young artist, filmmaker and graduate of Haverford College. We originally met while participating in the ICA Open Video Call 2018, where I was blown away by her video Matir Shapla. In this interview I learn about her upcoming projects and recent work, some of which was featured in “Make Room for Me” at Little Berlin (now closed), which you can read about in this Artblog review by Natalie Sandstrom.

Morgan Nitz: I want to start by digging into your artist statement, because it is the very first thing you see when you navigate to your website. It starts with “I make poverty work”. Can you elaborate on this for those who are unfamiliar with you and your work?

Nishat Hossain: I’m thinking of work as both noun and verb in the statement, and poverty as both adjective and noun. So, the sentence can mean I make work about poverty, my work is the result of poverty, or that I manage to survive poverty under capitalism and somehow make ends meet. Poverty is a form of economic violence that capitalists justify as a necessary evil. Poverty, unemployment, starvation, and homelessness are ultimately meant to punish poor people, and scare them into compliance. And police of course are the apparatus of the state that helps maintain this class of poor folk. But, not only are poor people punished, they are also morally judged (e.g. it’s their fault for not working hard enough and not being intelligent enough to overcome the system, because there’s always a way out). There isn’t a way out though. The system is propped on a carefully crafted imbalance that’s fundamentally necessary to its survival. Poverty is economic genocide, and both my body and my body of work struggle to survive this hateful extermination for which we are blamed. When you’re poor under capitalism you learn how to make do with your resources, you make difficult choices and sacrifices, you cultivate an intelligence around survival and self-preservation. I think that’s what my work is about. I somehow manage to string together enough resources and support to put out new work each year, and the labor and logic of survival and scarcity mark my work.

MN: I read on your website that your thesis at Haverford was called: Yours Virtually: Materiality and Intervention in Virtual Media, which you say, “traced how virtuality is made present through the material of the body.” When you say virtuality, are you referring to Deleuze?

NH: I’m referring to the overall discourse about virtuality that Homay King outlines in Virtual Memory: Time-Based Art and the Dream of Digitality. While she does engage Deleuze, it’s her propositions, and not Deleuze’s, that interest me more. She points out how contemporary discourse constructs digital media, the internet, and virtual worlds as immaterial, disembodied, and unworldly, and her book argues how these are all actually bound by the constraints of material, physical, sensory, time-bound, space-bound, and earth-bound realities. King says that the virtual emerges from the interval of the present moment, that it is a potential reality that is separate from but still grounded in and continuous with the material of the present moment, and the past and future of this moment. This argument has social and political undertones, because as she points out, this myth of abstraction allows us to overlook lived and embodied experiences bound by the limits of time, space, and matter, and these include the experiences of race, class, gender, sexuality, and disability.

MN: Can you tell us a bit about this concept, your research, and speak to how it has influenced your practice?

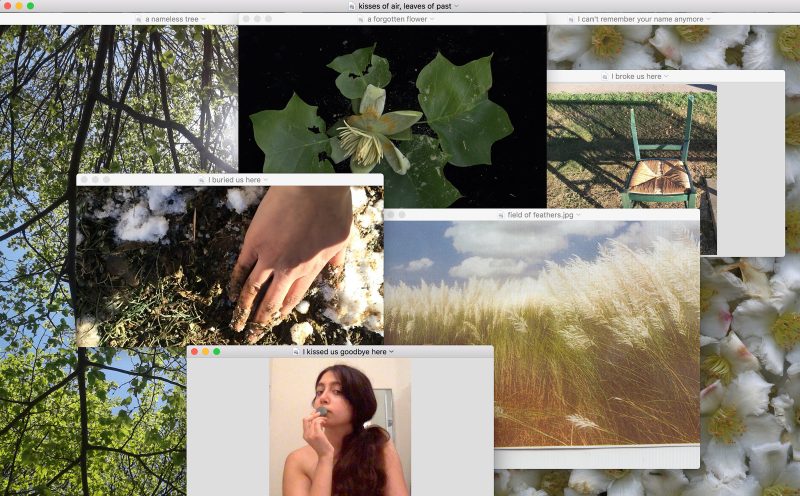

NH: My research practice is hybrid. I read and write things, but I also make and perform things. Both modes are equally important for me. So, for instance, when I was reading King’s theories for my senior thesis, I was performing close readings of texts and applying them to analyses of select images and performances. But, as I was doing this, I was also playing around and performing with digital and virtual media as a way of thinking through these texts and images. I found myself repeatedly making artwork about my body, and even when I would write and do more formal research, I would still keep returning to my body and finding a way to write its experiences into the academic paper I was writing. This process of making work about my body and the concept of virtuality that I was exploring through the process, helped me realize that every work I make in any virtual or digital medium is grounded in my body and the social and political realities it experiences, and not an abstraction of my body and its experiences. I remember earlier in my practice I made what I then understood to be abstracted representations of my body. But, that’s not what my works are; they are bodies in their own right, and have meaning and potential outside of what I assign to them. This is especially the case for the digital photographic works I began making in 2017. The viewer can browse between the texts and images held by the windows in the photos to construct a potential narrative, but there is no one authoritative narrative that takes precedence.

MN: Your work often involves writing. I was particularly struck by the text in “Song Offering”, a video that collages clips of yourself with semi-transparent clips from Bengali Renaissance Cinema. Over all of this appears:

“I am/ disappointment/ and love/ I love you the way/ the sun warms your skin/ I clothe you/ in warmth/ but am beyond your touch/I’m with you / and not/ I’m not with you/ in the ways you hoped/ I’d be/ But nor am I without you/ in the ways you feared/ I hope this finds you.”

The punctuation in the last line changes from an exclamation point, to a question mark, until you ultimately delete the phrase entirely. This is allowed by the moving image, as is the opportunity for us to witness the speed in which you write these words. The pace is defined by the editing process. Would you categorize this work as writing? Maybe performance? A video that deals with text?

NH: I was thinking about editing in both the context of writing and making videos and images. How can the editing process, that is the process of production, be the work itself? The video is made entirely on my laptop. I use my laptop camera to take a video of myself removing bandages and covering the recording camera with them, write the text for the letter in the notepad app, collect songs from Bengali Renaissance cinema from Youtube, then toss all these materials into Adobe Premiere and throw effects onto them. The meaning of the work for me is in this process and the compulsion that I felt in wanting to go through the performance of this process. I remember the most common critique I received after finishing the video is that it doesn’t make sense (have a cohesive narrative or structure), that the text is unreadable at times, and that there isn’t aesthetic coherence (the text, video of me, and film excerpts don’t find a confluence of aesthetic flow). But, the work isn’t in the video. The video is a residue of a performance I did on my laptop: the performance of taking off and putting on my bandages, touching my hair, staring into the camera, searching for old Bengali musicals, writing a hesitant letter to my mother, editing a video, and posting an excerpt of it on Vimeo and my website.

But, going back to the question of text, performance, video, and editing, I’m reminded of Orit Gat’s essay “Could Reading Be Looking?” The essay talks about how reading is a form of looking in both the culture of internet browsing and gallery and museum wall labels. When the eye encounters the body of a text it wanders over it the same way it might the body of an image. There are bits that catch your attention and bits that don’t, and the eye drifts over the entire body, comparing what the authority that created this body says to what your body thinks and feels about what your eye is looking at. The verbs of looking and reading can be used interchangeably in describing the action of engaging images and texts. You can read a text and look at image, but also look at a text and read an image. Reading and looking are similar performances. Writing and making images are also similar performances: you’re making marks, placing elements, making choices, editing, and re-editing.

If I had to categorize the work I would place it in the same category as old Bengali cinema: not video, text, or performance, but sentimental kitsch. These movies and my video are things my body needs because it is needy and wants comfort. These movies bring me soothing nostalgia, and the process of making this video was a form of consoling play.

MN: Can you tell us a bit about the work you showed at Little Berlin last month?

NH: The work at Little Berlin was a video and five photographs. The video was “45 minutes” (2016), while the photographs were “CRATE” (2018), “Not Trouser Word Piece” (2018) and three images from a series I began in 2017 called birthday girl. My body is in present in each work. Each work is very different, but in every work I grapple with the question of what it means for my body, in particular, to occupy space and make art. I think that when artists like me make work it gets relegated to being flattened as work about belonging to a particular identity, instead of being valued for its insights into contemporary culture, the state of the world, universal experiences, and the human condition. The arts has a long, long way to go before it uproots its phobias of various identities. When artists like me make work, it’s still on some level perceived as a threat to constructs of male genius, white genius, and first world genius, and this threat is neutralized by flattening the value of our work to our identity. People feel unable to acknowledge how our identity is a source of intuition, intelligence, and criticality that is essential to thinking through the existential questions that rove through all our bodies. We’re seen as less than human. When artists like me make work, we destabilize the myth of genius. Genius is a capitalist construct, and within the context of the art world it plays a very particular role. We all have an innate brilliance within us, but social inequity chooses to only nurture a select few above others. There is no genius, but there is power and privilege.

MN: Do you have any upcoming projects you’d like to tell us all about?

NH: Well, I just finished two digital photo works, one called “Mosque of Melancholy” and the other one “Minaret.” They’re two very different photographs, but still connected in their themes of grief and spirituality. I also started a small photo project currently titled “Tumi Amaro” about Suchitra Sen. She’s a Bengali actress who formed my ideas of film, photography, desire, and intimacy. Her image will forever touch me, and the project is a way for me to understand the closeness I feel with her images.

A bigger project I have in progress right now is A History of Darkfinding. The piece is a performance-lecture commissioned by Bryn Mawr College for the contemporary section, co-curated by Kate Dolson, Elena Gittleman, Matthew Jameson, and Laurel McLaughlin, of the 12th Biennial Graduate Symposium titled Irresistible Night, Ageless Dark: The Nocturnal in Image, Text, and Culture. In the piece, I consider the relationship between darkness and the body. I have a meditative night-time walking practice from which I’m constructing a series of movements and gestures that convey the waves of thoughts and feelings the darkness carries through my walking body and wakes it with. I’m then choreographing these movements into an experimental performance lecture. In the lecture I’ll be narrating and performing an alternative history of western knowledge production that counters the Enlightenment tradition with what I term a tradition of “darkfinding.” I’ll be telling this history by way of Pre-historic Indian and Medieval Golden Age Islamic astronomy and night time Quranic and Hindu meditative traditions. Of course, the work is still in its early stages, and might alter with time, but that’s the process I’m employing for now. The symposium is on November 15th and 16th at Bryn Mawr College (and open to the public), and I’m honored and excited to be a part of it.

I’ve found that my recent works are increasingly about the criticality my upbringing in Muslim and Bengali cultures has equipped me with in relation to both the world and the images that make it. I think I went out of my way to not make work about either parts of me when I began making art in 2014, because I was scared of being stereotyped and flattened and worried that my work would be seen as easy, unrigorous, and about “being Muslim and Bengali.” It’s ok to be white or male and make work about it without being flattened. No one tells you work is white work or man’s work or easy. But, if white artists and male artists have the right to unapologetically make work about their bodies, so do I. My work is not immigrant work, third world work, Muslim work, Bengali work, trauma work, or any other currency of identity that marks my body. I make poverty work because it resists this logic of currency that abstracts and stereotypes bodies. My work is love and vulnerability. My work is my body.