Some Do Not Need the Ground

On the occasion of Jacolby Satterwhite’s Room for Living at the Fabric Workshop and Museum

by Rush Jackson

The act of freefalling can be liberating or terrifying; depending on who you ask. Some folks become more acquainted with a sense of weightlessness than others, who may have been granted the privilege of being grounded.

Some cling to the idea of the ground.

Some do not need the ground.

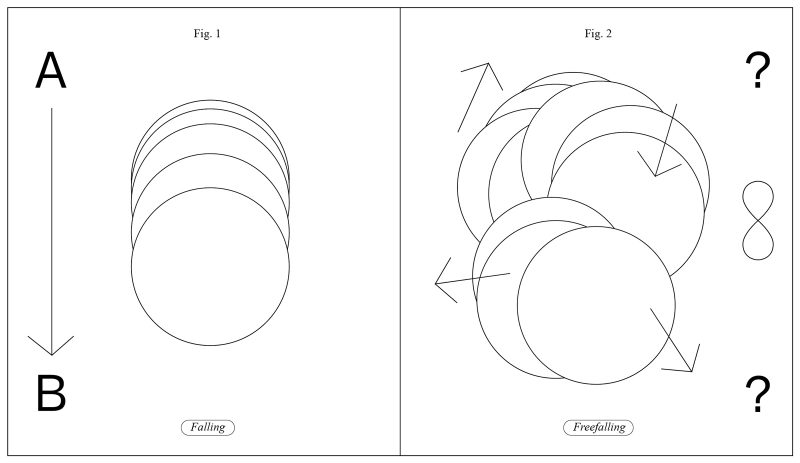

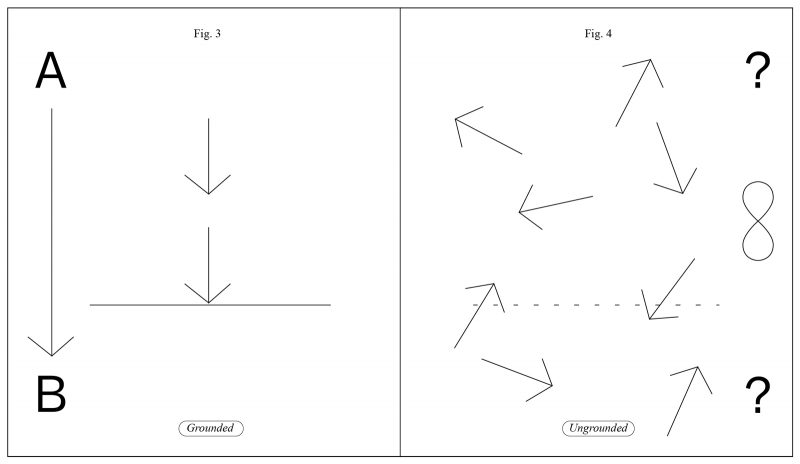

The act of falling, more literally, is the result of gravity exerting force on an object in physical space. (see fig. 1: object 1 falls from A to B.) With the idea of freefalling, it is implied that there is no plane to be grounded on, no specific endpoint to a rapid and unpredictable descent/ascent. (see fig. 2: object 2, in a perpetual state of falling.) To illustrate further, freefalling can feel like “skewed life chances”, to quote one of Sadiya Hartman’s characteristics of the afterlife of slavery, and it can also feel like “Available Balance: $5.27”, to quote a statement from my Bank of America app earlier this October. With the lack of security that comes with it, freefalling can be a terror-inducing state of being—a life without grounding. However, it can also function as a crucial space of play, where new form and language can develop. Room for Living, Jacolby Satterwhite’s first museum solo show at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, makes clear that Satterwhite’s “Room” doesn’t need grounding to be inhabitable. Satterwhite’s universe has its own logic—one with varying, even contradicting gravitational pulls. While freefalling can often be a deterrent to one’s prosperity, Satterwhite has used a personal and familial history imbued from a lack of security to create an idiosyncratic language out of crisis/lived experience. Some do not need the ground.

Room for Living—a culmination of Satterwhite’s universe, and two years of close work with the FWM Studio Team—asserts itself as a milestone in Satterwhite’s career and mythology. Spanning two floors of the Philadelphia museum, RFL stages an overview of nearly a decade of the artist’s work, along with new installation work fabricated with the assistance of the Fabric Workshop and Museum staff. Split by floor between installation and digitally based work, the whole of Satterwhite’s practice is readily visible in one space. While communicating themes of queer identity/culture, Western art historical symbolism, Room for Living also depicts figures in flux; lives with no stable footing. Nonetheless, Satterwhite has carved a space that’s not only inhabitable, but a place to thrive and envision new and alternative futures.

The upper floor of the show reveals a vast space, scarcely adorned with two large screens, projecting both channels of “Blessed Avenue” (2018), playing loud enough to fill the entire floor. A capella songs by Patricia Satterwhite—Jacolby’s mother, a self-taught artist suffering from schizophrenia—travel across space, synthesized and edited into a larger overall auditory collaboration with musician Nick Weiss. In the distance, Domestika hangs from VR cables coming from the ceiling, resting right above multimedia installation “Throne” (2019). Satterwhite’s practice is known for joining disparate elements together in a very 21st century, very Cubist, very Black way. “Domestika” (2017), and “Throne” (2019) are examples of this logic playing out the curation of the show; two works with different temporal contexts living together at the same time/space. “Throne” is an installation comprised of an area rug, velvet chairs, plastic plants, and neon text. While functioning as a seat with which to sit and view Domestika on, “Throne” exudes a kind of domestic humor, offering itself as a substrate for “Domestika;” a filter to experience it through. “Domestika” situates viewers through a virtual tour of an invented world—half utopia, half dreamscape—a world filled with many people in motion, seemingly working towards a common goal. A similar scenario plays out in “Blessed Avenue,” as both video works implement Satterwhite’s signature repetition of bodies moving throughout the composition. While these figures bring to mind voguing and ballroom culture, as well as S&M culture, Satterwhite uses the figures in video work as a kind of formal punctuation/notation throughout the works. Recognizing the semiotic connotations of a body, Satterwhite is able to use bodies to create a landscape in a composition or emphasize their motion. Satterwhite is able to make a distinctly formal building-block from a body or bodies, and their motion, or lack of motion. The lower floor of the show is largely devoted to Satterwhite’s newer installations, made with support from the FWM Studio Team. These installations are largely sourced from an earlier work, “Reifying Desire” (2014). Works like “The Remote Control for Cock on Wheels” (2019), let Satterwhite’s lexicon expand into a physical space. Using appropriated drawings of material culture inventions Patricia Satterwhite made, Jacolby Satterwhite brings these objects to life, creating neon-lit shrine-like installations of the objects, as well as using scans of her drawings through different works, such as “Room for Doubt.”

Familial ties and personal history are at the core of Satterwhite’s work. From the creative history of Patricia Satterwhite, to his own; these histories reflect the context he grew up in: Black and queer, suffering from cancer from youth. Satterwhite’s early life got him acquainted to the idea of life in freefall. Stable ground didn’t come easy to Satterwhite with age, as he eventually deemed painting an exhausted mode of production for him. During a lecture at UPenn, discussing some negative critiques and feedback as his time as a painting grad student, he stated, and I paraphrase: “You can’t be Black with Impressionist gesture—painting gets in the way.” While painting has been praised for its contemporary indexicality, this indexicality is not afforded to all. Blackness disrupts the assumed-by-default indexicality. But working through the lack of grounding afforded Satterwhite new modalities of communication, expression, and resistance.

The vast array of works in Room for Living are an amalgamation of Western art historical prowess, personal and familial histories, and matrilineal logic. Satterwhite shows us what a career of radical language building looks like—and how to design a world that better suits who you are. Satterwhite’s work is at once a reaction and comment on centuries of western art discourse, a conjuring ground to bring forth familial mythology, and a generator of language/form for the Black Radical Tradition. A conjuring ground for the ungrounded; form given for the journey towards (a) Black queer utopia(s).

Bio

Rush Jackson is an interdisciplinary artist, designer, and writer working between New York City and Philadelphia. Selected regional venues Jackson has exhibited their work at includes ICA Philadelphia, American Medium, High Tide, Icebox Project Space, Vox Populi, and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

rushjackson.com