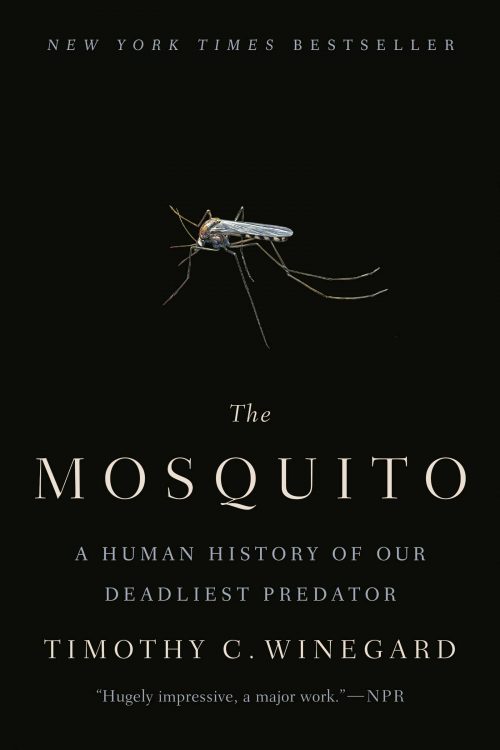

Timothy C. Winegard, “THE MOSQUITO: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator” (Penguin Publishing Group, 2019 ISBN 978-1-524-74341-3)

Every year, close to 700 million people are affected and over a million killed by mosquito-borne diseases (malaria, dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, Zika, chikungunya and lymphatic filariasis). According to the World Malaria Report by the World Health Organization, in 2018, malaria took 405,000 lives, 67 percent of whom were of children below five years of age. Africa alone accounted for 94 percent of all malaria deaths. The mosquito has single-handedly killed 52 billion humans through the 200,000 year course of human history.

In addition to tracing the biology and morbidity of mosquito-borne diseases in his new book, The Mosquito: a human history of our deadliest predator, historian Timothy C. Winegard explores the key roles that mosquitos have played in shaping human civilization and even the genetic make-up of human beings.

The rise and fall of empires in the Middle East

Beginning as early as 1200 BC, Winegard charts the role that mosquitoes played in the rise and fall of greater Middle Eastern empires including the Babylonian, Assyrian and Hittite micro-empires. Besides being plundered by the Mediterranean islanders, these empires were ravaged by natural disasters and malaria epidemics.

The mosquito protected the Greek Empires from invasions by the Persian Empires

The rise of the Greek and Persian Empires began around 550 BC. However, attempts by the Persian Empire to conquer Greece failed, largely as a result of mosquito-inflicted dysentery, typhoid and malaria, which were contracted by Persian forces when they were forced to traverse marshy terrain to attack Greek towns. As Winegard explains, this enabled Greece to become the next superpower, giving the world great thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Hippocrates.

The role of the mosquito in the creation and destruction of Rome

The role mosquitoes played in the creation and destruction of Rome is the most intriguing part of Winegard’s book. Deadly mosquitoes bred in the 310-mile long Pontine marshes along Rome’s coast, and they weakened every invasion, including invasions by Carthaginians, Vandals, and Huns.

However, as the Roman empire expanded, “(crop) cultivation increased, fostering further mosquito ecologies on the rural fringes of the city, including the Pontine Marshes,” Winegard writes. The rapid development and expansion of the empire – including urban beautification projects such as fountains, baths, and ponds in which mosquitoes bred — coincided with natural floods, hurricanes and global warming, resulting in an onslaught of malaria epidemics and plagues, which all were important factors in the fall of the empire.

Christianity, Coffee and Tea

Interestingly, Winegard points out that mosquito-borne illnesses contributed to the flourishing of Christianity in Europe, because Christianity was viewed as a healing religion. As the author says on P. 105, quoting Irwin W. Sherman, professor emeritus of biology and infectious disease at the University of California: “Christianity, unlike paganism, preached care of the sick as a recognized religious duty. Those who were nursed back to health felt gratitude and commitment to the faith, and this served to strengthen Christian churches at a time when other institutions were failing,” .He also concludes that the popularity of coffee and tea is attributable in part to the fact that they have been considered to have healing properties against malaria. But to clarify, the author is not endorsing coffee or tea nor are doctors, but stating that there is some evidence that both beverages or their chemical components (tannic acid, caffeine) have had some effect on some types of mosquitoes.

Winegard demonstrates that mosquitoes paved the way for the Slave Trade

The first effective treatment for malaria, discovered in Peru in the 17th century, was quinine, from the Cinchona tree. Quinine enabled European colonizers to reach and settle in the Americas and other tropical environments, including India. Unfortunately, colonization and intercontinental trade also brought malaria to the Americas, decimating indigenous populations, which did not have access to quinine. Slave trade from Africa then was instituted by the colonizing Europeans to replace the lost labor of those peoples.

Sickle Cell disease

Thousands of years ago, humans developed a genetic adaptation against Malaria. Called ‘Sickle Cell trait‘, it was found first among Bantu farmers in sub-Saharan Africa nearly 7,000 years ago. The trait ensured 90 percent immunity from malaria to those who carried it. However, the downside (prior to modern medicine) was that it reduced the lifespan of those carrying the trait to a brief 23 years, writes Winegard. This would have been a blessing back then when human lifespan was short. However, today, this lifesaving genetic adaptation is considered an infirmity. One in twelve, or 4.2 million African Americans carry Sickle Cell trait today, writes the author.

Efforts to eradicate

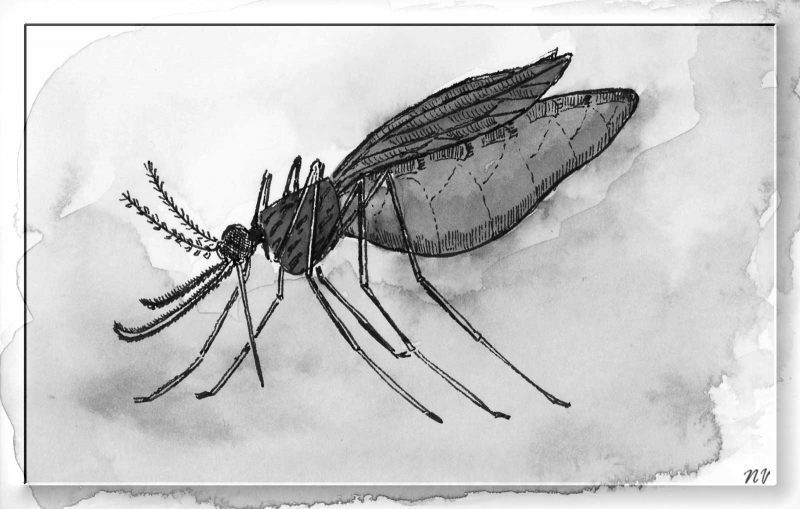

Global warming, of course, furthers the spread of mosquitoes and mosquito-borne diseases. At the same time, our efforts to combat and contain them – with drugs such as Atabrine, Chloroquine, and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), and insecticides such as DDT – have been thwarted as mosquitoes have developed resistance to them. There are some promising new vaccines currently in development and testing, but, as Winegard details, it is an uphill battle.

Meanwhile, Winegard highlights recent efforts by scientists using CRISPR technology, developed at the University of California-Berkeley in 2012, to alter the genes of the Anopheles mosquito to render it extinct or at least incapable of carrying malaria-causing pathogens. In 2016, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has been funding the cause since 1999, invested a total of $75 million toward this project.

Recently, a team of researchers at the Imperial College London were successful in using this gene-altering technology to modify the gene of female mosquitoes such that they only produced a male offspring. There were 600 mosquitoes in the beginning of the experiment, but by the end of it, since only male mosquitoes were being born, the population eventually reduced to zero. This method could be used in the natural environment to reduce the population of Malaria-causing Anopheles mosquitoes, suggest scientists.

Gene altering technology, which can be used to alter human genetics as well, of course, is controversial. As Winegard points out, there currently are some 3,500 CRISPR human gene experiments underway. There also is the concern that this technology may have unintended consequences upon our ecosystem and unleash catastrophes that we are not prepared to deal with.

The perennial war between mosquitoes and humans continues. There is hope that we may prevail through new technologies, but there remains a long way to go.