These days, breaking myself free of the desire to compulsively scroll through social media has become a gargantuan task. Like most people, I’ve found brief moments of respite reading, watching TV and films, and looking at art. But in trying to quiet my anxieties, I still find myself with the nagging desire to understand how art and culture more broadly can be catalyzed as a force for radical social change, rather than merely fulfilling our ever-growing need for escapism.

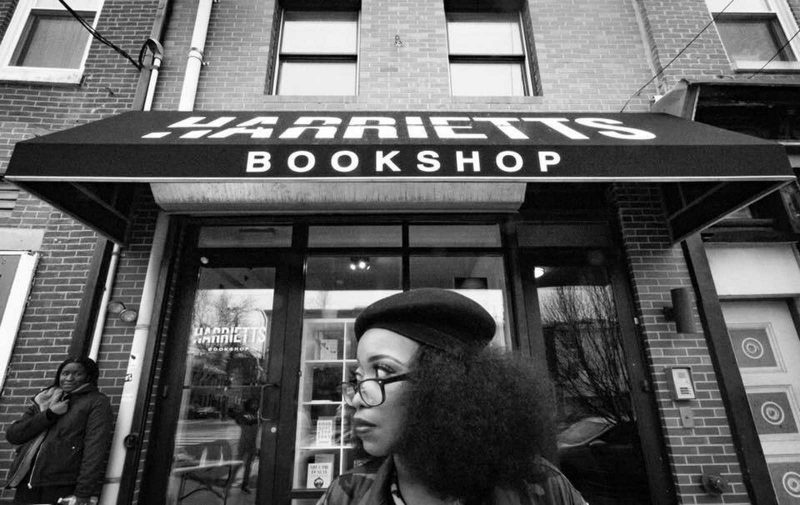

Several weeks ago, I spoke with Jeannine A. Cook, the owner of Harriet’s Bookshop in Fishtown. An artist and writer herself, Cook opened Harriet’s with the explicit intent of honoring the long tradition of Black women and their creative ingenuity, including the store’s namesake, Harriet Tubman. Prior to our conversation, Cook participated in a virtual roundtable conversation with the renowned artist group Studio K.O.S. which was hosted by Wexler Gallery. We spoke about art, activism, and Cook’s own journey as an artist and bookshop owner.

Cook began to cultivate her socially engaged practice at the University of the Arts, an experience she detailed during her conversation with Studio K.O.S. While studying at the University’s short-lived Media & Communications program, Cook and her classmates would check out camera equipment and go to her neighborhood in South Philadelphia to give local residents access to tools for storytelling. Through Positive Minds, a group she founded with her sisters, Cook also hosted workshops at her home where she invited community members to go through themed experiential exercises that encouraged participants to build meaningful connections with one another.

It quickly becomes apparent in conversations with Cook that her practice both as an activist and artist is informed by a deep and thorough understanding of history. Cook cites the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the organizers of the 1976 Soweto student uprising in South Africa as inspiration for her own tactical organizing efforts. Notably, Black women’s contributions in both movements were diminished in historical accounts. In our conversation, Cook commented on the irony of this exclusion from leadership roles in protest movements, saying, “[Black women] have a tremendous amount of power and ability to lead through certain scenarios such as the one we find ourselves in today…because [we] have been through some of the worst aspects of this society. We have an understanding of the entire circumference that many people don’t have.”

To Cook, the treatment of Black women within activist spaces extends to the lack of advocacy for Black women like Breonna Taylor who were murdered by the police and whose killers have yet to be held accountable. In addition to using her platform to amplify these women’s stories, Cook has made a point of her decision not to sit down with police officers during community meetings. While open dialogue is an integral part of Harriet’s operation, she underlined a need to maintain boundaries and her right to self defense and preservation, particularly in response to the large groups of white vigilantes armed with baseball bats who marched near Cook’s bookshop in June.

This approach to activism is rooted in Cook’s strong belief in the affective power of art, especially the written word. In her conversation with Studio K.O.S., Cook poignantly remarked, “I am highly susceptible to the quake in my spirit from words…I listen to words really intently and ask myself a lot of questions about when certain words are used and put together.” Written knowledge is a particularly potent tool which Cook put to use when she handed out free copies of Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero by Kate Clifford Larson and The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley during the protests in Philadelphia and Minneapolis. But Cook’s belief in knowledge as a tool is not limited to this contemporary moment. She often reflects on the ways creative practices are passed down through generations. This reflection motivates her to “[be] a good ancestor” by engaging in self-expression and facilitating the same sort of creative processes in others.

This vision for what art can accomplish is a necessary blueprint as we move our way through the massive upheaval in creative industries. As the mass layoffs and threats of permanent closure at many cultural institutions show, the model of a profit-driven and hierarchical art world which only tepidly engages with social issues is not sustainable. Cook’s multifaceted approach, wherein art and activism are not mutually exclusive and Black women are no longer relegated to the margins, is a much-needed template for the new world on the horizon.