My partner and I used to walk through the historic districts of Boston, our hometown, and wonder if we’d ever be able to live somewhere like that: blocks upon blocks of red-brick townhouses, occasionally interrupted by small parks with bronze statues and water fountains. When we moved to Baltimore six years ago, we chose Mt. Vernon as our new neighborhood. It seemed familiar to us, something like Back Bay or the South End in Boston. The architecture, for one, was very familiar. It’s the sort of neighborhood we wouldn’t be able to afford back home.

In Baltimore, we could. We found a place on the 900 block of St. Paul Street, presented to us as the best block in the best neighborhood of Baltimore. And I suppose it was. We had great light there from the sunsets. But, as with all good things, this had to pass. For reasons beyond our control, we had to move again after only two years in Baltimore. The only place we could find in the area, another rowhouse, was one block down on St. Paul. It was a back-facing unit, unlike our first place. And the ceilings were a little lower. While we may have gained in actual floorspace, we definitely lost substantial airspace. But the biggest difference between the two buildings was the facade. Our second place in Baltimore would be a Formstone Building.

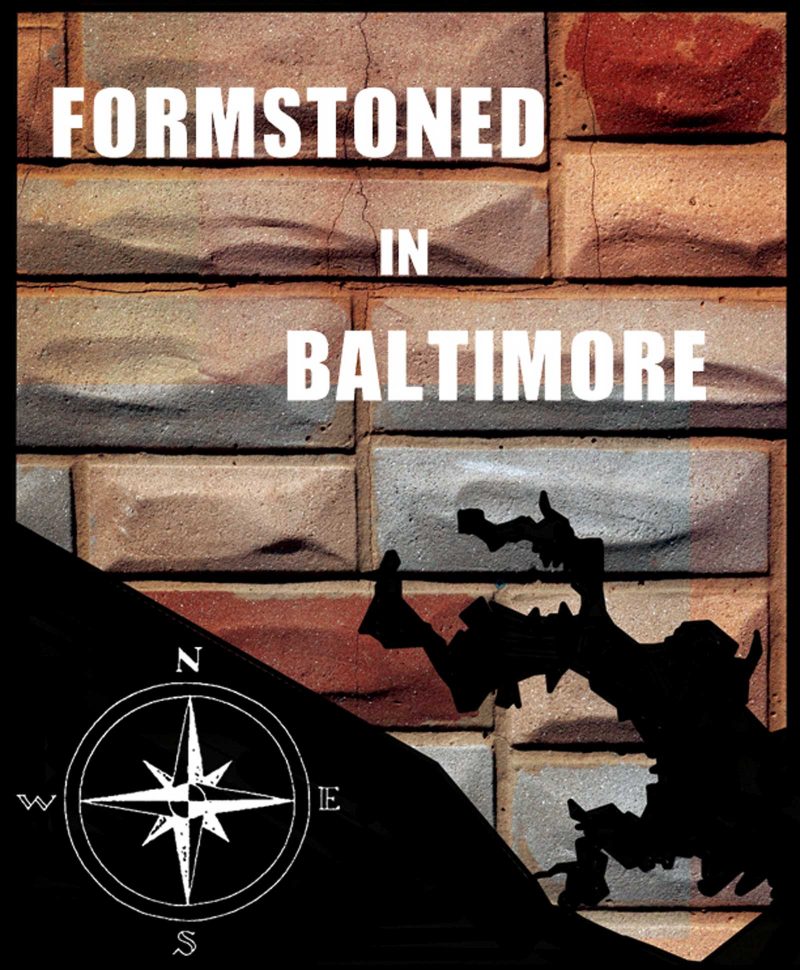

For those of you unfamiliar with the term, Formstone is a kind of cheap stucco commonly applied to degraded brick or stonework building exteriors in urban areas along the East Coast of the United States. This trompe-l’œil masonry is only shaped to look like actual stone and mortar. That is, the stonework of Formstone is completely illusory; the “stones” and “mortar” are of the same material. Much work goes into this conceit. It’s almost like a really good forgery: the counterfeit is almost more impressive than the original. Formstone is often multi-colored and sometimes mica is sprayed on after the fake stonework dries to give it a sparkly look. In short, Formstone is an architectural purist’s worst nightmare.

Formstone is strongly associated with Baltimore, as it was first patented there in 1937. While it can be found in other cities, Formstone spread like wildfire in Baltimore and is evident in nearly every neighborhood there. Many see it as a degradation of the earlier architecture, an affront to the neoclassical sensibilities found throughout most of the city. Others revel in its camp value and see it as a kind of Vintage Baltimore. John Waters, a local filmmaker born and raised in Baltimore, has referred to Formstone as “the polyester of brick.”

Perhaps a more fitting analogy would be with vinyl siding that has fake wood grain imprinted onto its surface. There’s no good reason to have that fake wood grain there; it’s not fooling anyone and it serves no function outside of a nominally aesthetic one. And yet, if you’re going to go the vinyl-siding route to fix up your home, you probably should go with the fake wood grain. It’s somehow better. It breaks up the light more and gives at least the impression of authenticity. The “impression of authenticity” is a strange expression, of course. But isn’t that what all art is? Picasso allegedly said, “Art is a lie that tells the truth.” Similarly, fake wood grain in vinyl siding and Formstone facades in rowhouses are lies that speak to a larger truth, one not readily noticed by a cursory glance or elitist assessment.

Like the fake wood grain in vinyl siding, the ersatz stonework in Formstone is a skeuomorph, “a derivative object that retains ornamental design cues (attributes) from structures that were necessary in the original.” In other words, earlier attributes, forms or “looks” (and even sounds) may linger in newer materials, media, and technologies. While it may seem like a contemporary conundrum – with our preoccupation with authenticity and what is “real” in the context of AI, Deep Fakes, and PhotoShop – the skeuomorph (from the Ancient Greek skeuos (σκεῦος), meaning “container or tool,” and morphḗ (μορφή), meaning “shape”) is evident in ancient architecture in the form of stonework references to wooden features from earlier structures that carried over into the design of later temples. Modern examples include electric light bulbs shaped to look like flickering candlelight; and fake wood grain (again!) on station wagons, a reference to the earlier horse-drawn wagon used to pick up folks at the train station. Skeuomorphs don’t have to be visual either. The click-click sound, simulating that of a single-lens reflex (SLR) camera, in a non-SLR digital point-and-shoot makes no sense at all. It’s only there to placate you. The skeuomorphic sound informs you that you’ve taken a photograph.

I’m already somewhat familiar with living in a building that has an under-appreciated exterior. If Formstone is a kind of “urban kitsch,” then the house I grew up in is an example of “suburban kitsch.” The previous owners had very peculiar tastes – to say the least – one of which was the salmon-pink aluminum siding that covered our home, and which I’m only now realizing was skeuomorphic in that vertical lines etched onto the surface of the panels were most likely meant to emulate the look of wooden shingles. Anyway, my older sister was so embarrassed by the color of my boyhood home that when she was in high school, she’d have her friends drop her off a few houses down. But one good thing about residing in a building with an unappealing exterior is that when you’re home, you don’t have to see it!

My parents also had a “brick” wall in their kitchen for several years until it was covered over by later renovations. Fake brick is doubly fake in that true brick is already artificial. As with the stonework that Formstone imitates, brick isn’t “real” to begin with, in the sense that it’s not readily found in nature –at least not in that form. The materials may have originated in nature – brick is basically dried clay, stone is stone – but they are transformed in a way that is hardly natural when used in construction. The point is, architecture is inherently artificial. It does not represent the natural world, but rather reconfigures it to suit the various needs of human beings. Formstone is a simulation of something already mannered.

***

We were initially placated by the familiarity of our first place in Baltimore: the red-brick and white-trim facades of elegant townhouses in Mt. Vernon reminded us of Boston. But we have come to appreciate the idiosyncratic charm of our Formstone home as well. Formstone, for better or for worse, is part of the urban fabric of Baltimore. In a city whose population has dramatically dwindled in the past few decades, and where block upon block of abandoned rowhouses and other infrastructure rot into ruins, the proliferation of Formstone illustrates the popularity of an affordable means to keep a building habitable and presentable. There’s no shame living in a Formstone-fronted building. In Baltimore, it’s de rigueur. When in Rome…