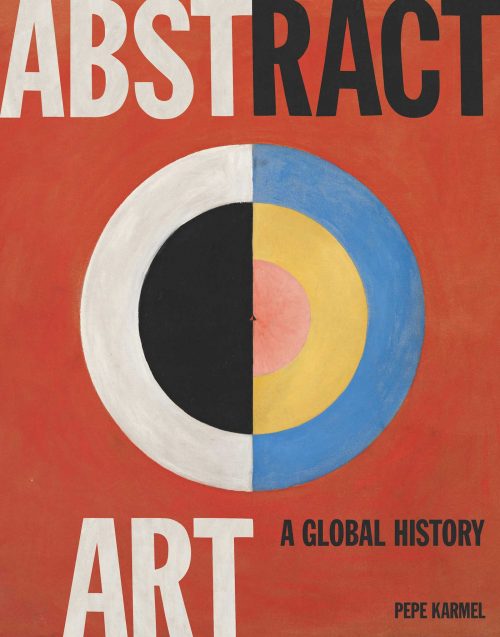

Pepe Karmel “Abstract Art: A Global History” (2020)

This carefully-conceived and beautifully produced book offers an original and valuable way to approach twentieth and twenty-first-century abstraction. It is written in an engaging manner that speaks to the author’s long teaching experience. Rather than charting abstraction as a successive progression of renunciation, he charts its origins in numerous subjects that artists have always addressed. Karmel begins: “Abstract art is always rooted in experience of the real world…. the true history of abstract art is not just a narrative of formal innovations; abstract art also offers a series of responses to social, political and cultural change.” He covers a range of sources under the headings of bodies, landscapes, cosmologies, architectures, and signs and patterns. The book opens with a thoughtful introduction to abstraction which includes changing critical approaches to the subject. Short essays discuss how artists address each of the proposed sources, but the bulk of the book is devoted to several hundred examples, each discussed and illustrated with full-page, color plates.

Karmel emphasizes that he is not proposing a new canon, but opening up the discussion. He is also not creating an all-encompassing history of abstraction. He takes a post-colonial approach that looks at the specifics of each artist’s circumstances as well as ideas they have in common, and gives equal attention to work by trained and untrained artists. One challenge to understanding abstraction is that many of its implications are easily lost when works leave their home territory. Similar formal means have expressed widely-varying ideas, and forms that had been well-established in Europe or the U.S. may be both radical and timely elsewhere. While Karmel’s examples are skewed towards New York collections (scholars never have global travel budgets), the artwork is thoroughly international and the volume includes numerous artists who have not previously been considered by mainstream writers and publishers. This book will be valuable for general audiences and students, and the breadth of examples will make it interesting to many specialist readers as well.

In the section on art inspired by maps and charts, Karmel discusses Kathleen Petyarre (Australia, c. 1938-2018) and her choice to paint with acrylics after the introduction of the medium by a teacher who worked in her Aboriginal community of Utopia; Petyarre had become allergic to the dyes she used for textiles, so switched to painting. Her motifs came from family legends and the local landscape and wildlife, and her language of dots originated in her community’s traditional body-painting used on ceremonial occasions. A spare woodcut by Zarina (India/U.S.A., 1937-2020) consists of a single line which meanders diagonally across an open plane. It’s form is the line drawn to separate India and Pakistan in 1947, which created massive exile and bloody consequences; armed conflict and exile were central topics for Zarina’s artwork. Mark Bradford (U.S.A., b. 1961) found the first materials for his collages in his mother’s beauty salon rolling papers, and later on the streets of his neighborhood in Los Angeles. His forms reflect city maps and their demographic markings, and his subjects include changing inner-city communities and their surveillance by government and police.

Pepe Karmel “Abstract Art: A Global History” (Thames and Hudson, London: 2020)

ISBN 9780500239582. Thames & Hudson | Bookshop.org

Antoinette LaFarge “Sting in the Tale: Art, Hoax and Provocation” (2021)

Antoinette LaFarge is interested in forgeries, hoaxes and impostures, and this book will appeal to readers who enjoy detective stories and mysteries as well as anyone who enjoys a good story, even if many of those LaFarge recounts are of questionable veracity. Her subjects include photographs of fairies, A Field Guide to Surreal Botany, a centaur’s skeleton, and a wealth of improbable organizations such as the Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and The Society for Nebulous Knowledge, and research projects including the Speculative Dinosaur Project and the Institute of Militronics and Advanced Time Interventionality. Her research ranges from the Classical period to the present.

LaFarge explores a range of what she terms “fictive art” that developed since the 1960s and expanded in the 1980s. The works have not received attention as a genre and employ diverse formats. All involve deception, with the artist often assuming a role in verifying the fiction as well as producing artifacts which bolster the story. Some of them invent artists or other personae, others purport scientific discoveries (fictive zoology, paleontology, archaeology), or institutions, associations, movements and even nations. In exploring fictive art, she looks at works that have rarely been considered in relation to one another. These include Marcel Broodthaers’ “Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles” (Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles), Andrea Fraser’s performances as a museum docent, Walid Raad’s projects of “The Atlas Group” and David Wilson’s “Museum of Jurassic Technology.”

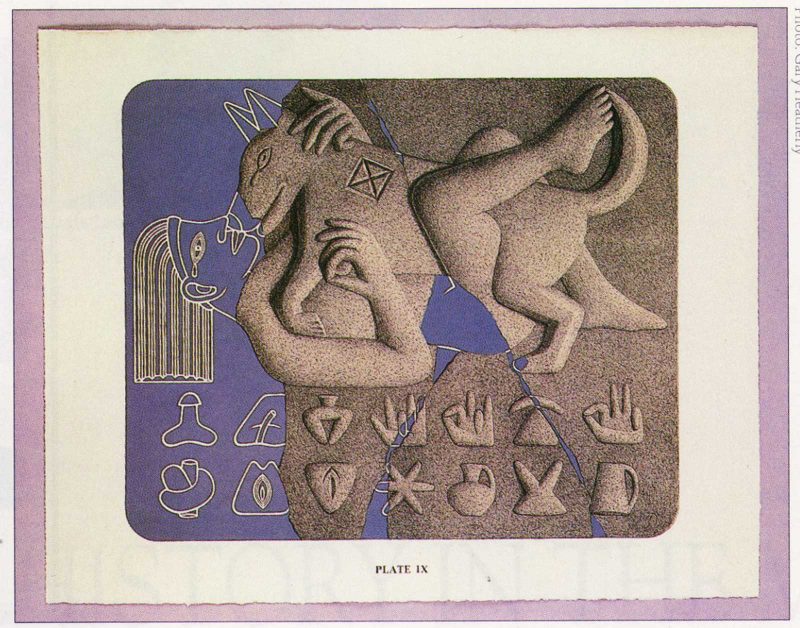

A paradigmatic work is Beauvais Lyons’s “Association of Creative Zoology,” founded in 1908, so Lyons says, and devoted to “zoomorphic junction” – the idea that unrelated species could produce offspring – in opposition to Darwinian evolution. Lyons supports the story with Biblical citations and taxidermy’d specimens of “divine collage”: a raccoon-crow, groundhog-fish and a gorilla-hen as well as lithographs which are comfortingly familiar in their resemblance to nineteenth-century scientific illustrations. He has shown the work at the annual John Scopes Trial Festival in Dayton, Tennessee, where it attracts responses from Darwin supporters and opponents.

Sting in the Tale is a serious study by a university-based scholar and practitioner but LaFarge’s examples encompass such an intriguing range that the book will pique the curiosity of many culturally-curious readers. It will certainly interest artists and others who care about questions of artists’ ethical obligations to their audiences, the authority of museums in establishing artifacts as art and verifying their authenticity, the role of educational institutions in producing official histories, and the possibilities of art as cultural criticism.

Antoinette LaFarge “Sting in the Tale: Art, Hoax and Provocation” (Doppelhouse Press, Los Angeles: 2021) ISBN 9781733957953. Doppelhouse Press | Bookshop.org

Make sure to check out “Books for Holiday Giving, Part 1“!