Jennifer Packer, unlike Jasper Johns, is too young as yet for a 2-museum retrospective like the joint effort produced for the 91-year old artist at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and The Whitney Museum of American Art. But Jennifer Packer’s two exhibitions, both of which I’ve seen — Every Shut Eye Ain’t Sleep at MOCA Los Angeles and The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing at The Whitney in New York City, contain ten years worth of an artist’s devout investigation into the psychology of observation. That is beyond an exceptional feat, considering the historical challenges for Black and women artists to acquire a show, let alone two simultaneously. At The Whitney, Packer takes up an overwhelmingly inviting space— the top most space— bringing forth my innermost wishes that Emma Amos had similar treatment at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and that she saw this precious exhibition for herself.

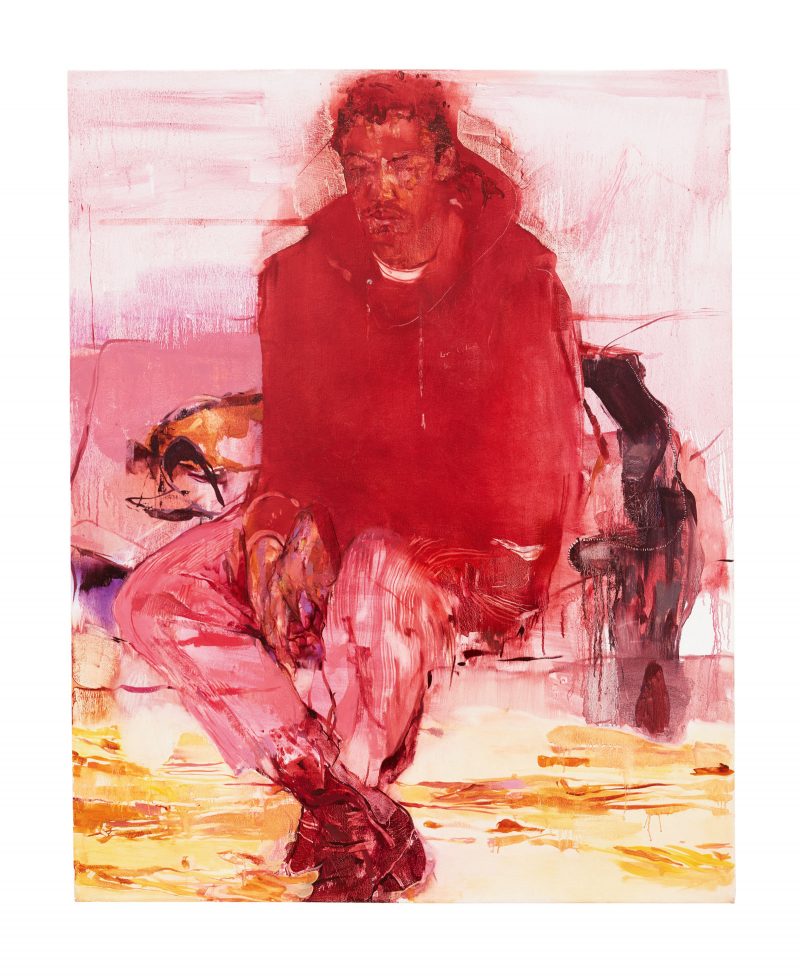

Once you take the elevator and exit on that enchanting eighth floor, the galleries have that presidential suite impression— all grand and spacious with lots of natural light coming through. Packer’s paintings and drawings of friends, artists, and grief hold tremendous emotional and psychological weight. In the ethereally glowing “Lost In Translation,” two figures are mysteriously shrouded in warm yellow hue; parts of their faces and bodies rendered; bent knees, clasped hands, thrown back head and windswept locs. The muted pink of a fleshy bottom lip, the brown shoe in the left corner, and the scandalous piece of bright white trim around a muscular bent knee are incredibly provocative. A viewer could become immersed for hours studying Packer’s extreme precision and care of these passionate individuals; using monotonous color and soft brushstrokes to capture intense feeling.

Situated among other simple wood framed drawings that contain much heavier contrasts, I turned then towards “Untitled” (2014), believing Malcolm X (or young Malcolm Little) and young Martin Luther King Jr. were present in a full-length charcoal drawing showing an impressively nuanced exercise in balancing negative and positive space; gestural lines and massive volume. At closer inspection, a young boy sits on the shoulders of another boy; their bodies producing a cross shape. The boys looked like an unmeasured history of Black innocence coming back to haunt a world that robs them of their chance to be just children.

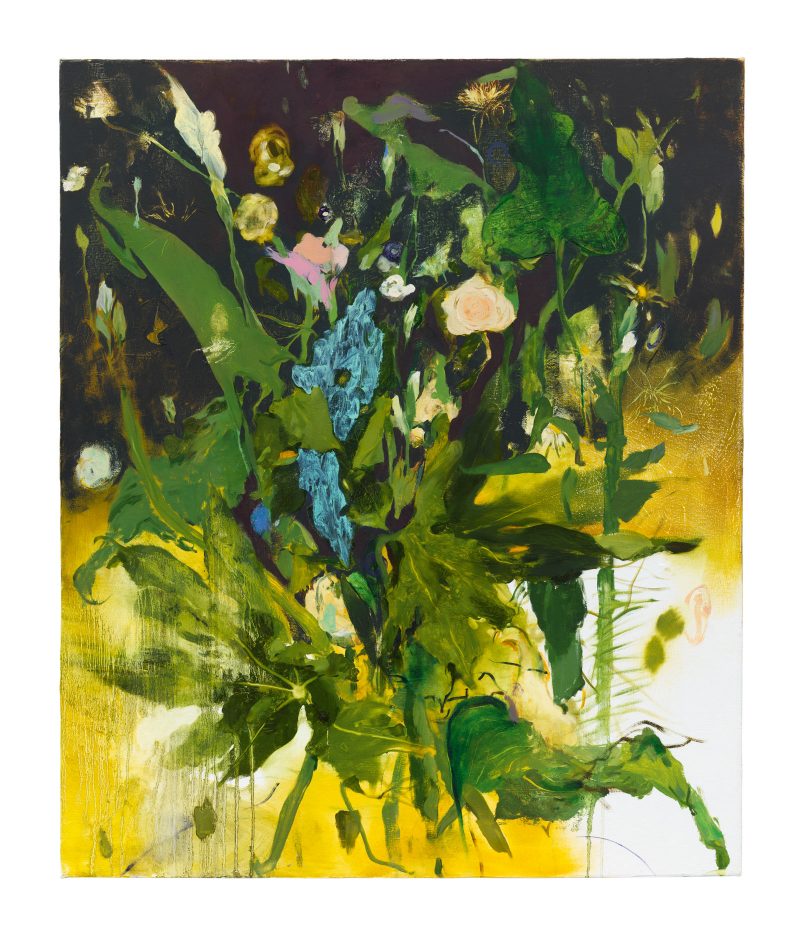

The exhibition offers a confounding education to witness Packer’s phenomenal growth into further exploring volume versus mass and crafting interesting color palettes. For example William, one of the earliest pieces on view, is a tiny, thinly applied painting featuring a solitary figure encased in turquoise, perhaps looking down on a beach deck. Such a small scale, which reminds me of a Polaroid, requires intimacy and calculation. The much later– and larger– “Say Her Name” is a rich funeral bouquet beginning with bleak darks, pliant green leaves, and surprising blues ending with saturated yellows and raw white – a much more sophisticated and complex color palette and masses.

The subject of “Say Her Name” and its title openly critique the violent act of absenting Black women and girls in conversations regarding police brutality and racial discrimination, adding a new bold layer of political and social commentary to Packer’s body of works. Sandra Bland, Aiyana Jones, Rekia Boyd, and others form a long, depressing line that we cannot ever forget. Perhaps this painting also gives flowers to the ancestors beforehand— those without proper graves, those lost and unknown, and those who will never receive hashtags.

The placement of the Emma Amos exhibit represents a tired condition from whence Black artists came. Jennifer Packer shifts the narrative to where they can land if given the opportunity— an opportunity to occupy museums simultaneously. As a fellow Black woman painter and draftswoman bravely traveling through a life or death pandemic, fueled by urgent inspiration and ancestral obligation, it was a true honor visiting both exhibitions in the same week and documenting the lasting impact these women have internally encouraged. I did not exit the elevator with the crowd for Jasper Johns fifth floor domination at The Whitney and immediately turned my back on his main gallery occupancy at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I could not ever detract from my mission to see Packer and Amos. They’re who I came for and who I hope to honorably cement in memory.

“Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing” on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC, through Apr 17, 2022