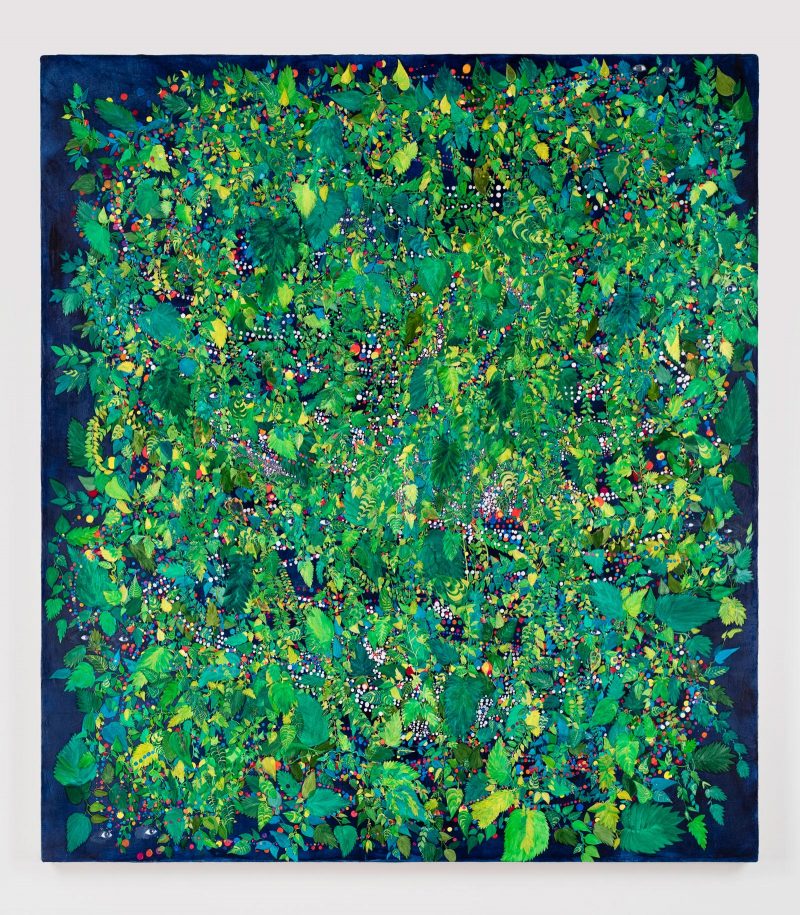

I am thinking about Sarah Gamble’s show Theory of Everything from my kitchen window, which overlooks an unruly bamboo thicket. Her paintings of dense vegetation have the same shimmering cadence as the light breaking through the wall of deep green plants, turning yellow and white at the edges and almost blue-black in the shadows. I half expect to see something or someone peering back at me, as the floating eyes do amongst colorful dots and trellised plants in Gamble’s “Acacia” (2021).

In her third solo show at Fleisher/Ollman, Gamble continues building on the visual language of her earlier work using constellatory dots and dashes. These delicate marks are combined with abstraction in hovering fields of color, as well as symbols both surreal and esoteric. Theory of Everything also includes more recent paintings of stylized foliage, a shroud of green that weaves around mythic figures and strings of dots.

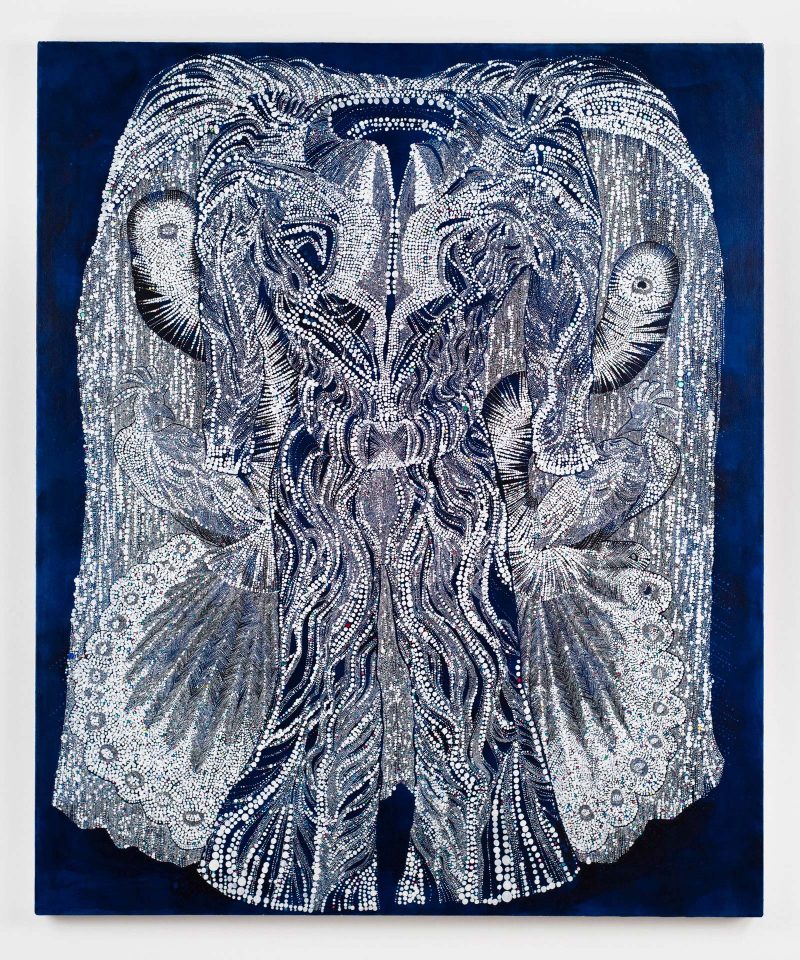

Of the twenty-three oil and acrylic paintings in the show, many are of an intimate scale that invites close, contemplative viewing. The larger canvases expand into celestial environments, such as “The Fantastic” (2021). A cloak made of a thousand tiny white dots hovers on a night blue ground. The garment is flanked by two peacocks, whose feathers fan around it. Peacocks recur in Gambles symbology, an image borrowed from Elvis Presley’s extravagant satin costuming.

I read the show’s title, Theory of Everything, not as a universal maxim, but as a participatory gesture toward the fabric of the whole. Gamble conjugates realities, collapsing human vision with the scale of an insect or the interior of a star. Hers is a cosmology which fits within the smallest seed and yet opens into the furthest reaches of night.

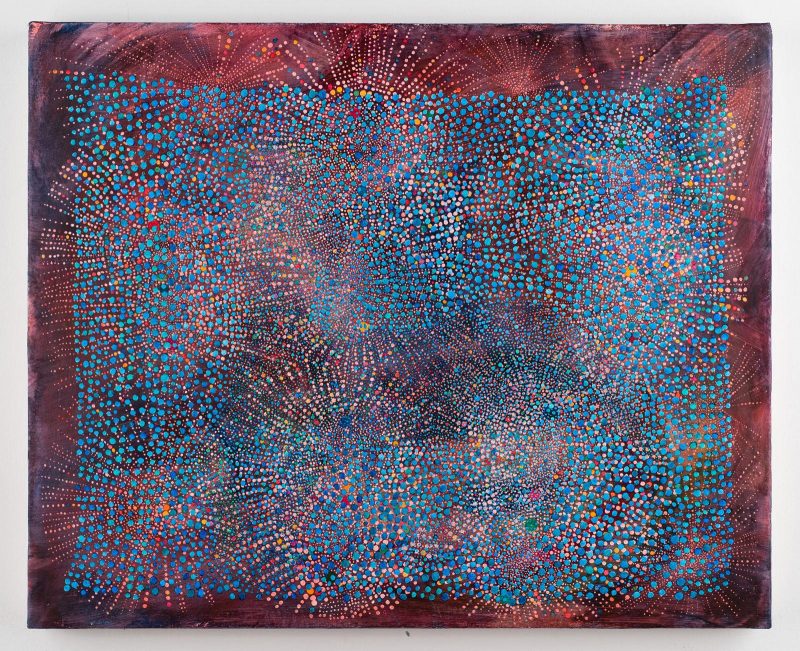

Gamble’s mark-making echoes natural structures just enough to feel as if it was not made entirely by human hand. It feels post-human, not in a doom and gloom apocalyptic way, but as an ecology wherein language is shared across beings. Some of my favorite paintings in the show are the small abstract works, like “Hologram “ (2019): a rectangle of mostly blue dots float above starbursts with flecks of red, and yellow atop a pink-brown brushed ground. The visual texture is that of a sea urchin, or aster flower, minute points shifting gently as the eye focuses.

Long has the spiritual dimension of abstraction visited painters as a companion or guide, but within Western critical narratives it’s often stigmatized in favor of formalist analysis. Hilma af Klint is remembered for her early contributions to abstraction, while her theosophical and spiritualist philosophies are seen as the means to the paintings’ ends. The surrealist Leonora Carrington was institutionalized against her will for her occult and hermetic visions that appear in her paintings and short stories. An undercurrent of the spiritual-abstract is the emphasis on receptivity in the creative process; it is only through remaining open to all that is unseen, that the physical image is made.

Gamble’s paintings participate in this lineage overtly in her frequent choice of surreal compositions—a peacock and crystal float atop a billowing red tapestry, a self-portrait as the queen of swords. They also evade direct interpretation and instead offer spaces to contemplate the magical in relation to living.

The eco-feminist and science fiction novelist, Ursula Le Guin, describes in her essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” a cultural theory suggesting the first device among humans might not have been a weapon, but receptacle—a basket, blanket, or pocket—in which to hold things. Le Guin uses the carrier as a metaphor for creativity which gathers disparate things into a whole without hierarchy. I see Gamble’s kaleidoscopic worlds as an effort toward a speculative realm, wherein the spiritual, the creaturely, astronomical, atomic, and Elvis all bump into each other, and new poetry is formed.

Rather than a self-serious contrivance of a mystical encounter, Gamble approaches the otherworldly through the back door of play: taking the colorful and familiar into the realm of the fantastical.

“Sarah Gamble: Theory of Everything” is on view until March 12, 2022 at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery. Reservations are appreciated but not required.