Western printmaking history traditionally begins with the Guttenberg press and books, and after that, German etching/lithographer extraordinaire Albrecht Dürer and stretches onward to Japanese wood blocker Katsushika Hokusai, who inspired Impressionist painters such as Vincent Van Gogh and Mary Cassatt. In postmodern art history, the great Elizabeth Catlett — of African and Mexican heritage — briefly enters the dialogue with her tremendous contributions on Black women migrant life and prolific historical figures boldly carved on wood and linoleum. If you’re not studying beyond what your instructors highlight, it usually does not go any farther than Catlett on the existence of Black women printmakers. Belkis Ayón, Margaret Taylor-Burroughs, Ruth G. Waddy, Emma Amos, Ayanah Moor, Margo Humphrey, and countless others barely receive mention.

Thankfully, Tanekeya Word’s Black Women of Print exists; combating the absence of Black women printmakers, through its mission to “promote Black Woman printmakers via accessible educational outreach.” Currently, the Black Women of Print have their first New York exhibition called A Contemporary Black Matriarchal Lineage in Printmaking on view at Claire Oliver Gallery. Tanekeya Word is exhibiting with eight other Black women printmakers: co-curator Delita Martin, LaToya M. Hobbs, Ann Johnson, Karen J. Revis, Lisa Hunt, Stephanie M. Santana, Chloe Alexander, and Sam Vernon.

“Like our foremothers, Black women printmakers have used the tools in our hands to create visual languages that tell the stories of our past, present, future and the in-between spaces within fractal time,” said Word in the exhibition curatorial statement. “Each printmaker shares matriarchal perspectives on Black interiority.”

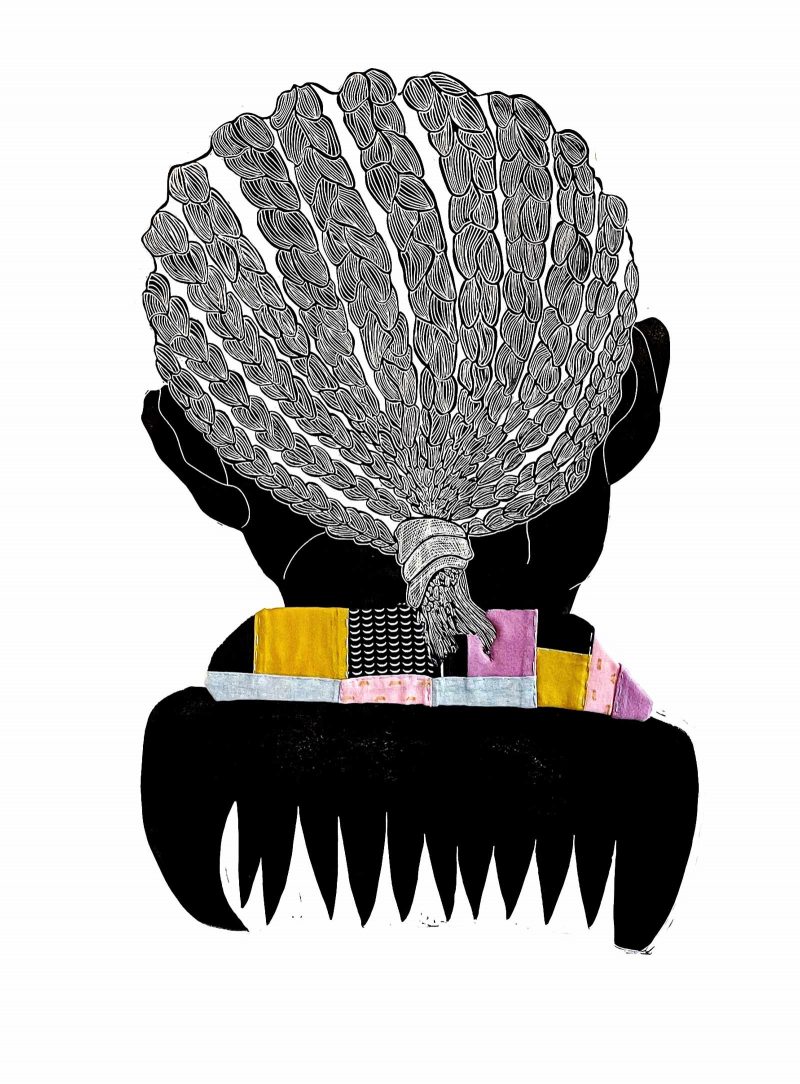

Black Women of Print came to my attention two years ago during my personal quest to build the Black Women Make Art Database. I was struck by Tanekeya Word’s impressive prints of Black women’s distinctive hairstyles merging with various stylized African combs. Her heads tell the stories of sophisticated braids and twists, of elaborate barrettes and designer Afro picks. Word incorporates other mediums such as ink, watercolor, and stitched fabric into her varied printmaking techniques ranging from woodcut to lithography and monoprint.

Delita Martin’s powerful multidisciplinary etchings have been on the radar since her solo exhibition “Between Spirits and Sisters” at the Galerie Myrtis in Baltimore. Her works also played a prominent background role in Stella Meghie’s film The Photograph which stars Issa Rae as a curator at the Bronx Museum. Martin uses repeated patterns in the backdrops of her highly rendered figures— mostly women— crafting intriguing breaks between the spaces of her charcoal forward portraits. Family and family history are imperative in her practice. Martin says, “there is definitely a strong emphasis on genealogy in my work. I grew up in a very close family and we were taught to value and preserve our family history. I was quite fascinated with the stories my grandmother, grandfather, parents, aunt, and uncle would tell. I saw them as paintings and I was in awe of how they could paint with words. So it was natural to bring this into my own work.”

Martin works out of the Black Box Press Studio that she founded in Little Rock, Arkansas. Last year, Black Box Press Foundation hosted its first Arts As Activism Fund, an artist grant program in a mission to “advance the work of today’s artists and… recognize and honor how artists have had a vital role in political and social history.” and will have an artist residency in the near future.

Overall, Black Women of Print members are sharing deeply personal stories that migrate from artist to artist. LaToya M. Hobb, maker of some of the largest woodcuts in the whole world, has an astonishing attention to detail to thought-provoking works defining love and tenderness. Chloe Alexander presents commendable portraits composed on sanded mokulito plates (lithography on wood!) and Stephanie Santana seams intimate family photographs onto beautifully patterned silkscreens. Yet a monoprint of an X with teardrops called “After Belkis” by Sam Vernon drives everything home— that urgent yearning to create and remember those before like the utterly tragic Belkis Ayón.

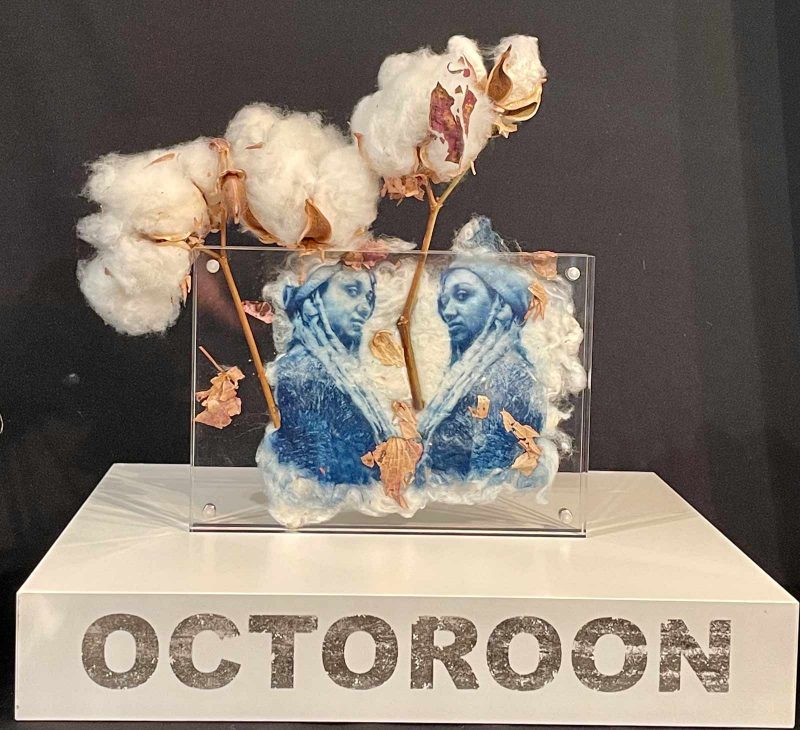

The other women demonstrate how far printmaking has come from flat surfaces. For example, Karen Revis prints black inked faces on handmade paper, Lisa Hunt breaks apart silkscreens and adheres them on panels, and Ann Johnson uses intaglio and integrates found objects together, creating unique installations on her mixed ancestry. Yet activism is not a far away thought for her. “Since 2015 my art has steered more towards activism,” Johnson says to Strange Fire Collective. “A great friend told me to ‘use your art as your activism.’ 2014-2015 was extremely significant because of Philando Castille, Tamir Rice, Eric Gardner, and the killing of [other] unarmed black folks by law enforcement. But Sandra Bland was close to home. Sandra Bland was home.”

Black Women of Print has been a valuable resource to the community since its inception. They offer opportunities to apply as members by meeting certain skill criteria and have programs that train printmaking to future Black girls and women. In addition to the Black women collectively joined by their love of all printmaking forms— silkscreen, lithography, collagraphy, letterpress, etching, etc.— the Black Women of Print website includes glossary terms for those unfamiliar and wanting to learn about individual processes. Printmaking is not a cheap practice, but the inaccessible gatekeeping makes it so that certain communities cannot gain knowledge without the required tools. With Black Women of Print on the move to honor timely contributions while making new ones, we can only hope that they continue pressing onward.

“A Contemporary Black Matriarchal Lineage in Printmaking” will be up until March 19, 2022 at Claire Oliver Gallery. The next Black Women of Print exhibition— “What the Mirror Said” titled off a Lucille Clifton poem, will be held at the Richard J. Brush Gallery at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, March 7, 2022- April 14, 2022.