After seeing Now’s The Time at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks at the Brooklyn Museum, King Pleasure, my third Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition experience, offers further insight into the brilliant, trilingual artist’s short life and career. With over two hundred displayed artworks and objects, curated by his two sisters Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux, King Pleasure takes place inside of the spacious Starrett-Lehigh Building in Chelsea. Sir David Adjaye OBE— the prominent designer behind the Smithsonian’s National African American Museum of History and Culture— beautifully recreates the Basquiat family home, holding up a three-dimensional scrapbook to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s biggest fans. Instead of the typical white gallery walls, the rustic wood makes the exhibition appear more homey and inviting— less institutional. Basquiat’s edgy, sharp persona shines through works that are as attractive and charismatic as the artist himself.

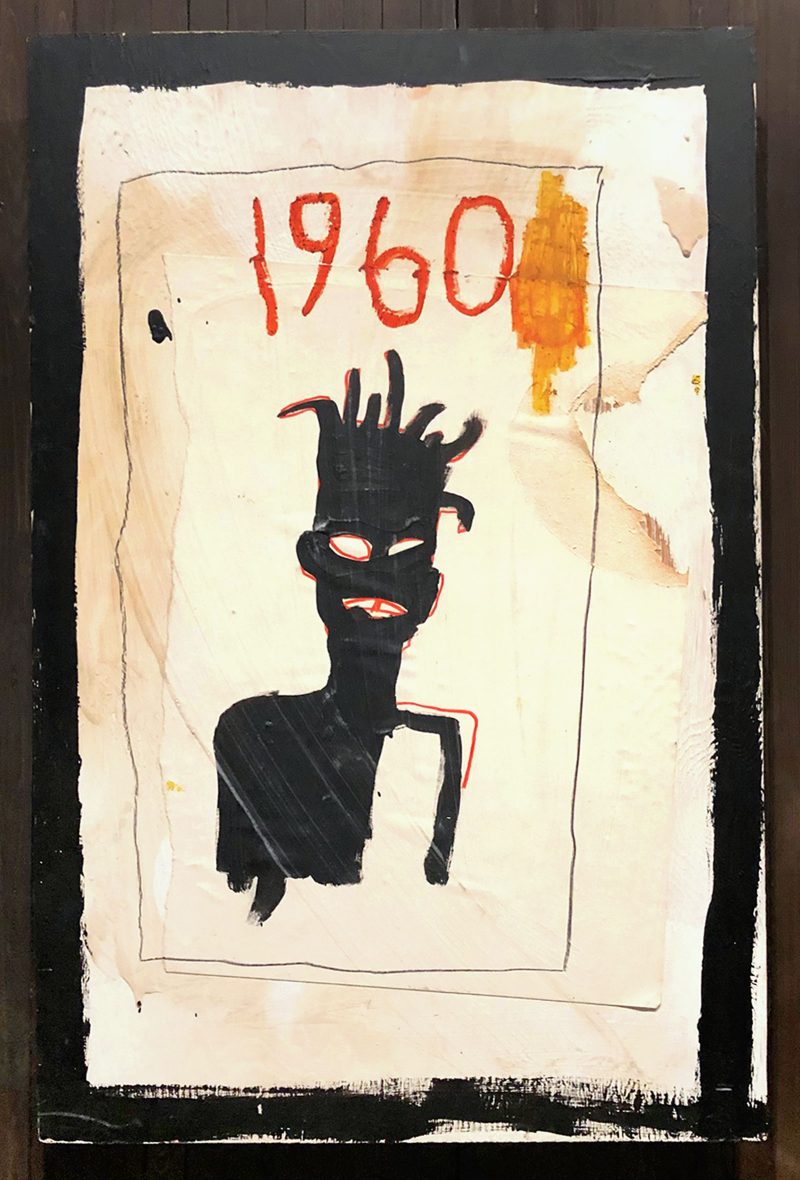

King Pleasure begins with enlarged photographs of Basquiat and high-resolution reproductions of his text-based work. The late artist’s soft-spoken voice recites abstract poetry from the unseen speakers. Viewers are advised to move straight forward and not venture backward. The first room contains mixed media drawings and paintings. Basquiat’s three self portraits are hauntingly stark silhouettes. In “Untitled (1960)”— the year he was born is scrawled in red-orange. The figure’s eyes appear direct despite containing no pupils. The parted mouth shows his diastema— the distinctive gap between his two front teeth. Locs rise above his boxed head. “Untitled (Self-Portrait)” continues Basquiat’s investment in composing together the pure essentials that make him— his locs, the space between his teeth, the symbolism of his black skin achieved by the smooth, rich oil stick. In “Untitled (1984),” layered over two collaged drawings, the figure’s lips are sealed and the eyes are entirely colored white— the sclera (white) apparently taking over. In the two separate drawings, a shoulder blade is drawn over pink paint with the word “scapula” crossed out and an ivory carving floats next to an elephant. The interest in naming objects and actions, turning artworks into pictographs, is a prominent theme.

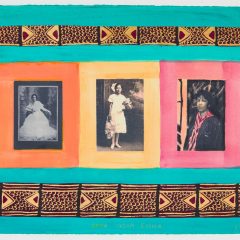

This room also features a map of Basquiat’s frequent New York City haunts, a baby blue birth announcement, and VHS home videos of his childhood with his sisters Lisane and Jeanine and proud parents, Gérard and Matilde. Andy Warhol’s massive silkscreen portrait of Basquiat closes this chapter. The second room has silkscreen prints of Gérard, Jeanine, and Matilde on the left side wall and farther down, recorded videos of his family sharing their fond memories. On the opposing side, Basquiat’s quirky high school drawings and writings from his time as illustrator for City-as-School Newsletter, teenage sketchbooks, and various drawings and writings ranging in subject from cartoons to police brutality.

After passing through the Basquiat family’s reimagined vintage living room and classic kitchen (old family photographs are projected onto the living room wallpaper), gorgeous abstract paintings and drawings take over the main area of wood walls painted creamy off-white. Basquiat dissects art history, especially the white canon, societal expectation, and Hollywood stereotypes. He bares his entire heart and soul using language, gritty lines, and impactful color. His experiments on cheap paper, a refrigerator door, and found furniture showcase an artist on the brink of immediate urgency. “Cabeza,” an acrylic and oil stick painting on a blanket mounted on wood support, centers a fragmented, pitch black figure on a patchy, bright yellow background. The white outlines on the body include Basquiat’s mysterious word “AOPKHES” below the collarbone and carefully rendered internal organs. The figure’s face holds a sinister charm— the red outlined right eye larger than the left, the yellow and black squared teeth set in an open mouth, not quite smiling, and the few strands of wayward hair.

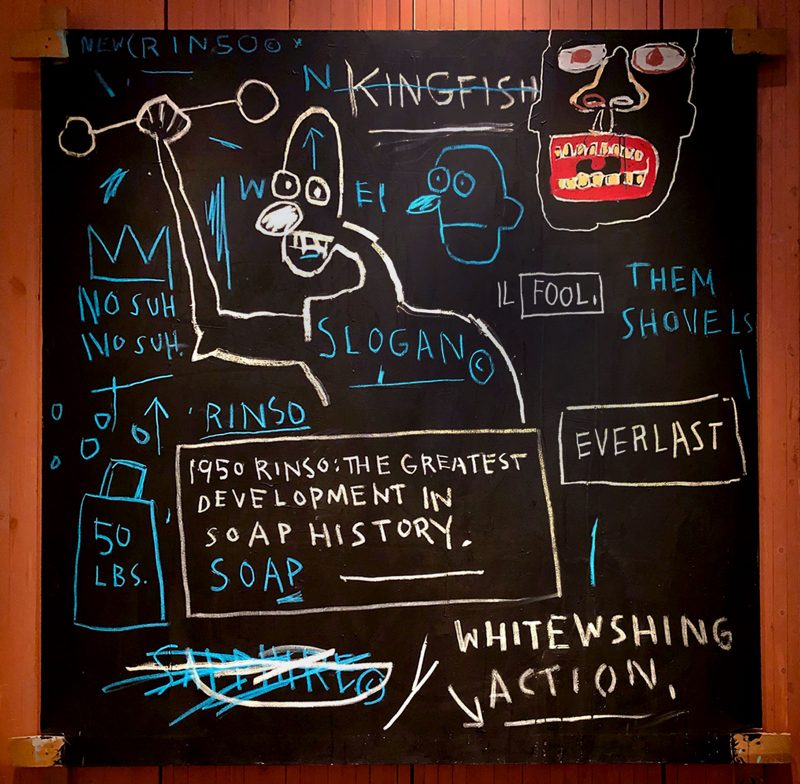

Basquiat does not censor his intentions. He is an artist keenly aware of his worth and uses that advantageous knowledge to advocate for himself and others. The anger-filled “Untitled (Rinso),” an acrylic and oil stick painting, on a stark black background, criticizes the industrial complex and capitalism by using the first mass marketed laundry soap in America—Rinso— “the greatest development in soap history.” Capitalized words take up most of this composition with the slave lingo “no suh” repeated under his trademark crown. A figure lifts up a weight and on the other side spells “Everlast”— a popular brand of boxing gloves. The words “sapphire” and “kingfish” are crossed out.

In a recreation of Basquiat’s IDEAL studio, his paints and oil pastels are neat next to a ceramic bowl filled with Marlboro cigarettes and a bottle of red wine. Stacked books include titles on “Egyptian Painting” and “Black Hollywood.” “Scarface,” “It’s A Wonderful Life”, “Amadeus,” and many other VHS tapes surround an old Sony television/VCR. His signature olive green jacket is hooked to the wall. A projection of him painting plays in the corner. For a moment, it certainly seems he would turn around, smile, and share the abstract poetry he spoke to you at the entrance to this exhibit.

The grand finale put me in more awe than I imagined possible. I was in the company of two monumental murals originally installed at the former Palladium nightclub’s Michael Todd Room, a VIP lounge. “Nu-Nile,” a forty-foot acrylic and oil stick work, consists of several panels with the dreamiest cinematic red tying them together. Once your eyes enter into this impressive composition, you’re actively engaged into deciphering meanings behind Basquiat’s inventiveness: exploding heads, earths, crowns, ebony black heads and ebony black figures, and copyrights/trademarks of words “petrol,” “oil,” and “notary.” In the mixed media collage, “Untitled (Palladium),” a yellow, red, and green dragon head charges forward over top Xeroxed drawings— all containing a fascinating head. In my many glorious minutes spent in its presence, my touched eyes performed the interactions my hands longed to. I found myself immersed in his intentionally struck out word lists, the bold contours and shapes (especially with teeth) in his profiled faces, and the wrinkled folds caused by adhered papers.

The strong, meaningful King Pleasure honors Jean-Michel Basquiat’s undeniable genius. Those who knew him best tell us that he was a brother, a son, a friend, forever missed. This is the chance to learn about the man put on the pedestal of Black art. Expect to be moved by his rarely seen art and writings, his travel to Africa, his DJ/ clubbing days with Grace Jones and the late Keith Haring, and the way the young nieces he never met vow to keep his legacy alive. Basquiat loved art in all forms and challenged the gatekeepers. To this day, he still inspires generations of artists to bravely take up the space they deserve.

‘King Pleasure,’ extended through September 3, 2022, is a timed exhibition located at the Starrett-Lehigh Building, 601 W. 26th Avenue, New York, New York 10001. Entrance is on W. 27th Street. Tickets can be purchased here. Hours are Monday and Tuesday 11am-6pm, Wednesday and Thursday 11am-7pm, and Friday through Sunday, 10am-8pm.