Four months ago, the art world lost commendable artist and art historian Dr. Samella Lewis. By demonstrating that art history scholars have the responsibility to emphasize the work of underrepresented communities, Dr. Lewis inspired my practice of redirecting the art history canon towards Black and women artists— most of whom are ghosts to unearth, analyze, and appreciate. Dr. Lewis was definitely on my mind during a past June exhibition of Vivian Browne’s “Africa Series 1971-1974” at Ryan Lee Gallery in New York City. I feel compelled to share Browne’s importance in painting and printmaking and express the value in supporting certain artists who are no longer living.

The late painter and printmaker Vivian Browne (1929-1993) was the third of four daughters, born in Laurel, FL, and raised in Jamaica, Long Island, by a father who moonlighted as a painter and a seamstress mother. At Hunter College in New York, Browne didn’t start painting until she was a college senior, receiving a Bachelor of Science and a Masters degree. Shortly after, she attended the Art Students League and later, the University of Ibadan, a research college in Ibadan, Nigeria. Throughout her career, she received various awards including a MacDowell fellowship. She also taught contemporary Black and Hispanic art, painting, and other courses at Rutgers University in Newark for twenty years; heading the art and design department from 1975-1978.

Vivian Browne’s artistic life and career is detailed in this surviving July 1, 1968 oral conversation between Browne and Henri Ghent (art critic/essayist and former director of the Brooklyn Museum’s Community Art Gallery) located in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art— home of the largest preserved collection of visual arts documentation. Oral histories shed insight into the past. The older the time period an artist existed in, the rarer it is to find audio of their voices, let alone a dialogue transcript. This brings to mind the traditional passing down of family histories from generation to generation; vocalized words and memory were heavy reliances meant to carry over without the aid of a recording device. It is a treasure listening to Browne, a startlingly gratifying woman who speaks candidly about her experiences at age thirty-nine with a sharp, clear remembrance. Nowadays it is much easier to access a contemporary artist through the prevalent immediacy of social media. During Browne’s time, however, positive word of mouth earned both an eager audience and the respect of a critic who wanted to talk with you about your life and practice. Browne is obviously considered a valued part of American art history, otherwise her legacy would not be saved.

In this particular passage, Browne describes her representational abstraction style to Ghent:

HG: Having seen a lot of your work, I wouldn’t say that you are a person who tries to escape reality, because it’s very realistic, almost everything I’ve seen that you’ve done. Do you feel completely compelled? What compels you to bring out this reality, to stop reality?

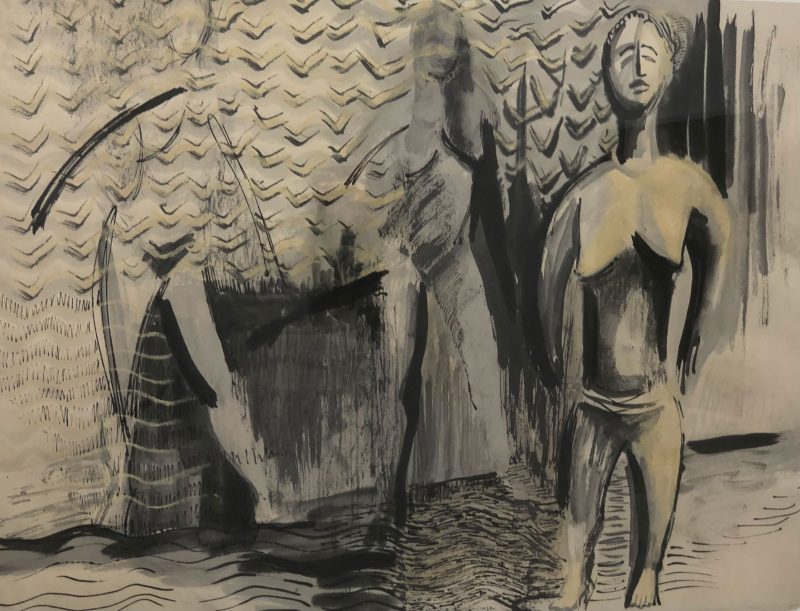

VB: I find that when I try to abstract an idea it’s merely an abstraction. But if I paint an idea in terms of a person of a sort or a person interacting then the idea is clearer and it’s more real somehow. I’ve always been strongly involved with form in painting, often to my regret. Because one can get hung up on form and just make a pretty form, and the idea’s gone. It’s always a battle. It’s not realism as we think of it. It’s more a flowing from an abstract expressionist idea with an actual person involved.

Browne’s “Africa Series 1971-1974”— inspired by her trips to Benin, Nigeria, and Ghana— showcases why she deserves a place reserved among the great abstract expressionists whether it be Harlem Renaissance artists Romare Beardon and Aaron Douglas or her female contemporaries Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell. In Browne’s painting “The Gathering,” the dreamy, mysterious composition is a complicated symmetry of repetitive interacting shapes and solid bodies with mask-like faces, the cool palette mainly in blues, oranges, and yellows. The title suggests the notion of collecting and contains eerie figures that may be conducting the act. Perhaps the deeper context lies in a more spiritual poignance— the African American traveler to the ancestral motherland harvesting concepts to fit into her painting style.

Although there is a substantial argument on the cons of investing in deceased artists, a case can be made for those who are not leveled with Picasso or Cezanne or any other white male breaking records at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and other art auctions. This argument is mostly addressed to publishers of updated versions of reprinted art history books and scholarly texts for not including Browne among her peers in the painting or printmaking movements of her time. Their contributions matter. Someone has to campaign for their work, let it be known that their practices are still valid, important, and influential. In art history texts such as Whitney Chadwick’s “Women, Art, and Society,” a book assigned during my undergraduate years, now in its sixth edition published in 2020, omits artists such as Browne from the abstract expressionist period dialogue. Even in books dedicated to Black art, the lack of women becomes a patriarchal issue. Dr. Samella Lewis’s “African American Art and Artists,” published in 1990 (and not featured in my many art history curriculums), includes biographies and images of over one hundred artists. “Image and Belief,” Dr. Lewis’s oral art history project published twenty-three years ago includes a few Black women artists from Margaret Rice Burroughs (1917-2010) to Carrie Mae Weems and Kara Walker. In fact, Lois Mailou Jones is the only Black woman painter mentioned. Richard J.Powell’s third edition of “Black Art” packs many artists, but Browne is not mentioned here either.

Art is incredibly vast and overflowing with centuries of creative talents, but the same names are always mentioned. Not everyone is going to exhibit at the MET or MoMa or the Louvre, but countless artists who made a significant impact will be ignored or otherwise forgotten. This endless exclusion of Black, women, and other minority artists has placed an almost uncertain future on art lovers, art scholars, and art writers as a whole. Most of us in the field have never received a full scope of the true art world during our expensive educational experiences. With this great lack jeopardizing our mindsets, blindsiding us into questioning what is good and bad art, what is worth our time and discussion, how can we ever move forward if the white male worshiping and gatekeeping continues onward?

Often, I reflect on the limited accessible information on Vivian Browne and hundreds of other past and present artists under the radar. It is my duty to give credit where credit is due. This Dr. Samella Lewis quote defines my role as a contemporary art writer invested in true inclusivity: “Black women are nurturers. We nurture our families by seriously listening to and seriously considering what they tell us. We also have an obligation to see that valuing and collecting contemporary art is a significant aspect of nurturing. We must familiarize ourselves with our historical and contemporary art in order to understand and know ourselves.”