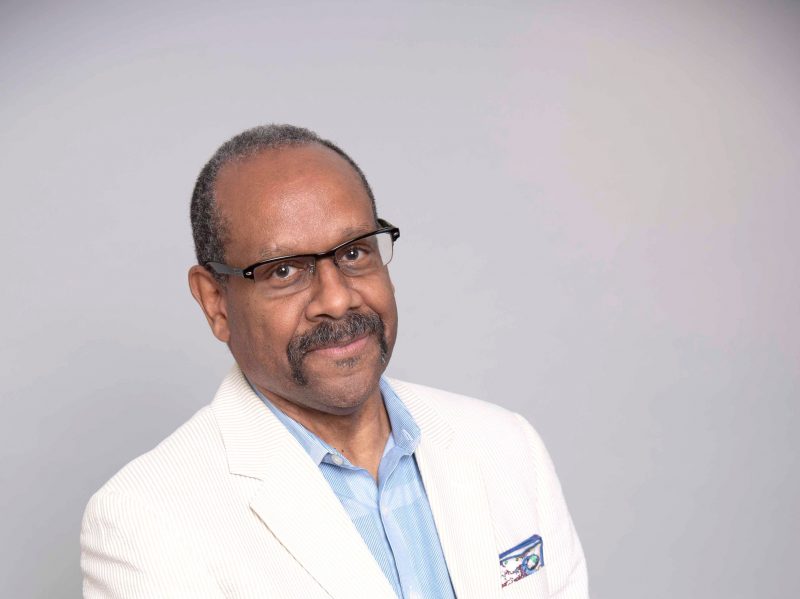

I met Allan Edmunds earlier this month at the Brandywine Workshop and Archives. Allan had invited me in for a conversation. He’s a great conversationalist and, as the founder of BWA who was on the verge of retiring, I wanted to get his view of the art world according to Allan. In a scant 39 minutes, the discussion covered a lot of ground, from World War II and the post-war GI bill and its influence on the African American community, to his blue sky, common sense ideas about building a better future. Captivating talk, I mainly listened.

Allan is a wise man, a doer and a maker with 50 years of experience founding and growing a wonderful arts organization that, since 1972, has hosted more than 450 artists-in-residence who have created over 1,100 prints at BWA; BWA has to-date established 18 Satellite Collections at museums, universities, and heritage centers in the US–joined by one in Cuba – and launched Artura.org, an online multicultural visual-arts and education resource that is dramatically expanding the global audience for BWA’s artists and the impact of their work.

He’s had trouble getting support in Philadelphia, whether financial backing from philanthropic sources or collegial and collaborative engagement from other arts and cultural organizations, and he’s frank about how he turned for support to those outside Philadelphia and found it in the national and global art worlds. His vision for the future includes helping Brandywine start an endowment for the Executive Director and being an advisor to its Board.

His wishlist for Philadelphia includes programs to encourage high school art majors to become arts educators; and a City insurance program to provide indemnification against liability claims for arts organizations who host visiting school groups. As he puts it, these are common-sense ideas that could really help the Philadelphia art world. Edmunds is a visionary and talks with missionary zeal about creating a better art world and a better world. And his advice for young people who want to start a non-profit in the arts is eye opening: Don’t start one but join an existing non-profit and work with them and learn what’s involved. Then decide if you want to start your own. By the way, he really wants to have more conversations with people. So reach out to Allan to share your ideas and to hear his. Also, Allan’s got a solo show at Woodmere Art Museum with an opening reception this Saturday, Nov.5, 5-7 pm. See you there!

[This interview took place on Oct. 11, 2022, at the Printed Image Gallery at Brandywine Workshop and Archives.]

The Warm Up

Roberta Fallon: Allan, I’m so happy to talk with you today.

Allan Edmunds: I’m so glad you came out to visit and hear what I have to say.

Roberta: You always are a good talker. You’ve got great genes for talking. I don’t know how you got em…

Allan: Practice over 50 some years.

Roberta: Oh it came before that. I think you were born a talker.

Allan: Nah, I was so quiet when I was in school.

Roberta: Well, I can’t believe it, but I’m glad you are this fountain of words now. Let’s talk about you. You’ve had this fantastic relationship with the Brandywine Workshop and Archives as its founder and Executive Director for 50 years. Congratulations! How old is Brandywine?

Allan: 50 years this fall. It’s starting to hit me. What is the equivalency of 50 years? Microsoft and Apple are not 50 years old. [Ed. Note: True, Apple is 46; Microsoft is 47.] Temple University (1884) and the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1876), PAFA (1805), so it’s equivalent to about a third of the histories of the PMA and Temple. It’s a different way of measuring 50 years.

World War II and its influence

Allan: I always look at World War II, the end of World War II. We’re, what, 70 years past that? And that probably created the greatest change in American society. People don’t want to talk about wars, but wars are responsible for the most major changes that are created in society. We experienced Covid, but in World War II women went into the workforce, because the men were away and for me, this was the start of the women’s equality movement..

It was so many things. The technology that came out of it; the auto industry, the home loans where people were buying homes who otherwise could not have afforded to do so.. So that created the need to build more homes. You had an option to live not in the core but to move out and build up the suburbs. And that created the need for mass transportation infrastructure projects. So a lot of growth and a lot of industries changed. Also the education changed with Brown .v Board of Education. In my mind all of that happened because World War II happened. And the whole world was at war. The most recent equivalent is Covid-19, where the whole world experienced it. Covid has caused major, lasting lasting changes in our society.

Roberta: Now, you’re retiring from your role of Director and Founder of Brandywine Workshop and Archives. That must make you feel a certain way?

Leaving Brandywine at a great time

Allan: I’m extremely happy that I can retire. Because my goal was not to retire and leave an organization in distress. I’ve seen it so many times, when people are just worn out, frustrated; they can’t do it anymore. In consequence, the organization is not in a strong position to survive that leadership transition. So, I’m excited. I didn’t want to wait 50 years to do it because life doesn’t always give you 50 years. So, I’ve been blessed with 50 years of life to do what I’ve always believed in, and I’m very excited about that because I’m going to leave Brandywine with no structured debt, an excellent staff–the best staff we ever had–the buildings are all totally renovated and updated, the technology, our computers, and everything that you would think that you need to be considered part of your foundational existence is there: location, ownership, facility’s in good shape, staff, great staff, great Board with great leadership and engagement. So, I’m leaving Brandywine at a great time, the best it’s ever been and that makes me excited.

Roberta: That’s a beautiful answer. I didn’t expect it. And it calls to mind that organizations don’t often change leadership and get better.

Building an institution

Allan: I mean, I’ve heard individuals say, “I’m gonna stay here til I die.” That’s about you; that’s not about the institution. The thing that I always hold up in my goal is, my original goal was to build an institution; it wasn’t to build a co-op, a relationship, or a community of people, but the institution would exist, and build the community around that. And people weren’t thinking that in the post-Vietnam War era. People were trying things. But I was never about trying things because I truly believe you need to build an institution, because people die, they come and go, they get frustrated and they leave. That’s normal, right? But what do you leave behind? And you need to leave behind something concrete so that the next generation can use it. So when you talk about change in society, you need institutional change. Without institutional change it’s only temporary. And we see that with Covid. We see a lot of change happening but it’s of the moment. What is the real structure? Do these institutions that now want to open up and become inclusive…To what extent is that going to continue?

Inclusion for 50 years, truth telling and documenting

Allan: I always have such great pride in the fact–and this is probably braggadocio–but I don’t believe there’s an institution in this country that for 50 years has been consistently inclusive, like Brandywine. And to continue to progress decade by decade and maintain that driver to your mission, which is not only that you do the best that you can but you do it with the most diverse group of people. You bring everybody along and you recognize their culture, their talent, regardless of age or where they came from. We’ve always been visionary at Brandywine.

This whole thing with Avenue of the Arts, which I told you before. [Listen to our 2019 podcast with Allan.] We were one of the main drivers, because it really was about the Kimmel Center. It really wasn’t about these other groups. So, I read the history and I know the story in detail. In a way, because I’ve been blessed with 50 years, I’ve become the truth teller. But that’s also a huge responsibility. And the responsibility lies in the fact that you’ve got to document. You can’t just say it. You’ve got to document it. And so we’ve been about documenting it for 50 years. Even when we didn’t have money we still tried to have catalogs; we still tried to do things to make sure that we had some source of documentation, so the history we were creating would not be erased.

Roberta: And you have to tell your own story. Otherwise someone else will tell it in a different way.

Letting the artist tell their own story

Allan: That’s right. Just like on our website. Matt Singer [BWA’s Editor-in-Chief and interim co-director with Marta Sanchez] will tell you, we emphasize authenticity on the website. Not what a curator or art historian says about somebody’s work, but somebody telling you what their intent was, the story, the image, whatever they were trying to convey. That’s so important because curators and historians can make you famous or hold you back. But when you have a chance to tell your own story and put it out there to a broad public, you’re really doing the artist a service, because they don’t generally have that kind of platform. And Brandywine is building that platform with Artura.org, where that can happen.

Sometimes I get pushback because people don’t believe the believable; they don’t want to believe you did what you did. Especially coming from communities of color. But if there’s any richness in this country, if there’s any definition of what American art is about, it is diversity. And you can’t define quality without being inclusive. There’s no such thing. Brandywine has been about exposing people here in Philadelphia, which seems to be historically parochial, to what’s going on in the wider world, particularly among communities of color. So we’re very happy about the legacy we created in our partnerships with other communities. We have our Satellite Collections. We are now in 19 university museums, art museums, and heritage centers around the country and in Cuba. And we’re hoping that by the end of our fiscal year, June 30, by that time we’ll have three more. And of course we just had a show, a three-month exhibit at Harvard, which was extremely well received. So, to put Philadelphia artists and organizations on the map with Harvard and places as far-flung as Nevada, California, Texas, Rhode Island, Maryland. We’ve done that so we should be proud.

I’m not one to boast but hopefully the documentation does it. If someone is willing to say, “Well, what Allan says is what he thinks.” But no. Look at the documentation. Go to Artura.org website. Go to our homepage. Come visit. It’s all there. If you want to learn what is there. But if you want to ignore it, fine. Can’t do anything about that.

Roberta: No. But you’ve done a lot to promote what you’ve done in a holistic community way. So you have roots in the community.

A global community but Philadelphia has not embraced us

Allan: Are you saying community is the art community broadly? Because I want to say Philadelphia has not embraced us. We’re not embraced here. It’s hard to get funding here. It’s hard to get artists to engage with us. But we get support nationally, and now we’re getting it internationally. Hopefully when I leave, we have a saying, “The brand goes to Brandywine 2.0.” And maybe we can make some progress with the level of support and acknowledgement that we get in our home community. But we get it globally now. When we say community, I’m talking about global community, I’m not talking about home.

Roberta: That’s interesting that you don’t get support here; and many organizations don’t get support in Philadelphia. I’m shocked to hear you say it but on the other hand it doesn’t surprise me.

Cultural Treasures should be supported and longevity respected

Allan: Certain institutions get support. That’s where our thinking’s so broke. There’s a recent program called Cultural Treasures, https://www.fordfoundation.org/news-and-stories/news-and-press/news/sixteen-major-donors-and-foundations-commit-unprecedented-156-million-to-support-black-latinx-asian-and-indigenous-arts-organizations/ where foundations outside Philadelphia have encouraged Philadelphia foundations to contribute to create a larger fund to support organizations that have been denied support. [Cultural Treasures is a collaboration between the Ford Foundation, which is national in its scope, and the regionally focused Barra Foundation, Neubauer Family Foundation, Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, William Penn Foundation, and Wyncote Foundation.]

And when I talk about support, it’s general operating support. Because it’s one thing if you say, “Oh, here’s a grant to go do a project, at 50% and you match it 50%.” What are you doing? And if that project doesn’t align with the mission and goals of that organization should they rethink it to come up with something that matches what they [the funders] want to fund?

There comes a point when there’s so many organizations that have their longevity and track record. They should be supported because they exist. Ok? Because they’ve proven they’re a treasure just by longevity and if you want to measure the extent of that then look at their record. How can you say we don’t get any support at the level I believe we should? Like I said though, I don’t want to sound like I’m complaining, because maybe there’s something I could have done better to get that support. But when you’re told [your organization] won’t be supported until you resign…

Roberta: Oh my

Finding partnerships and collaborations outside the local

Allan: That happened 15 years ago. Ok. And I resisted that because I felt like that was arbitrary. If I am still good for Brandywine, then I shouldn’t be pushed to resign. And so what do you do when you’re a small organization like Brandywine? You cultivate individual support. And if you’re going to cultivate individual support and you stay local, you compete with all these other groups locally. Why you want to do that? So you create a brand and you create partnerships. And you do things nationally, in other regions, and if you get the chance to do something globally then you’re expanding who your audience is.

And for printmaking organizations, that can translate into more print sales. So, we’re not even competing with the local galleries that sell art. We organized a website for print sales, brandywine.art. And anybody anywhere who knows about the website can access it, and they can look and they can order prints. So we’ve been doing that. Technology’s allowed us to build a platform for the website, but our history has been hosting national and international artists and there’s a market for that artwork, if you have enough diverse inventory across styles and everything. So we give people a lot to choose from. And it helps.

But you know, Philadelphia’s never been a city to really nurture something that…I don’t know how to say this, and I don’t mean to sound complaining. Look, if you don’t have challenges, how do you get a chance to grow and improve?” My mom always said, “Nothing beats a try but a failure.” And “You never fail if you don’t try.” So Philadelphia always gives us the opportunity where we can try to make progress. We can try. And that challenge is what hopefully creates some sense of innovation, too, in trying to meet that challenge.

Roberta: What would you say to a young person who wants to start an organization?

Young people who want to start nonprofits

Allan: Don’t. I haven’t found a young person, except my generation, Jerry Givnish [Painted Bride Art Center], Joan Myers Brown [Philadanco], everybody that started organizations that are organizations. They were the bedrock, the beginning of that situation. Because the NEA came into existence in 1965 and opened the doors to national and federal money. Then you had the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts and in 1991, 1992, the Philadelphia Cultural Fund came into existence. My wife, Anne Edmunds, having experience with the National Endowment for the Arts and the PA Council, deep, long-term experience, was recruited to set up the Philadelphia Cultural Fund.

But here, in this generation. Now here’s a complaint. This generation thinks you can start a nonprofit and get a salary. OK. I see it too much. They’re like mercenaries in the arts. They do it for as long as they feel like doing it but they don’t work to create an institution. You take a place like the Wilma Theater, which has transitioned from its original leadership. That’s a hard thing to do. It takes work, it takes commitment, it takes a lot of integrity on the part of people who are supposed to be the leadership. But if the leadership is only doing it for their favor, for their interests instead of for their [institution’s] interests, then what are they doing?

And so you have all these groups. You have the Cultural Fund, with some 300 groups applying. There’s one group I read, they turned their living room into a studio for the neighborhood kids and then want to start raising money; or buy a building and I’ll put a dance group (or art program) in it and I’ll raise some money and that’ll pay my rent. The scheming is not about creating an institution. And I’m not saying it’s 100% but I’ve seen it.

Teaching in the public schools and doing Brandywine

Allan: In 50 years you get to see a lot. It’s hard work. When I did Brandywine, for 25 years I taught for the School District of Philadelphia. I just didn’t do Brandywine. And I didn’t depend on Brandywine for a salary. That put me in a unique position, where I could think about Brandywine as Brandywine, and not something that’s taking care of my home. I also did other things, like real-estate development and stuff. So I worked hard at Brandywine but also worked hard at my own house to make sure that was in order and not dependent upon Brandywine. You don’t have people thinking that way now. Everybody’s looking for something different. “I’m tired of this job so I think I’ll start a nonprofit.” Oh come on, please. Don’t start a nonprofit. Go get some experience working in a nonprofit that exists so you’ll understand all the dimensions required of saying “I’m going to start a nonprofit.”

Arts Administration degrees, museums as closed circuits

Allan: And then you have Drexel, Penn and Temple, all these schools are teaching arts administration. We know there’s so few museum jobs that come up. And that’s like a legacy thing. Because people working there tell their friends and people they know are qualified and if an opening comes up, even before the public knows there’s an opening. We know the game, right?

So, we’re in this moment now where the museums are saying we’ve got to diversify our staff. It’s a window that is open but it’s going to close back, right? Are those people with that experience having worked for a major institution then going to look at the smaller institutions and say I can take the expertise I have here and apply it over there and make these institutions stronger? That’s what you want. You want people with experience. You don’t want to have people with no experience saying I want to start a nonprofit. That’s not even. It don’t make sense.

Roberta: Let’s talk about the city of Philadelphia, politics. What can the city do to help institutions like Brandywine? Is there anything?

CETA and the Visual Arts and Public Service program

Allan: Look, depending on who’s the mayor and what the budget situation is there’s always the opportunity to do more for the arts. When we started the Visual Arts and Public Service program with CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] money back in 1977, ‘76, the goal was to employ artists to work in communities so that the people living in the communities would experience a different level of value for art. It wasn’t being in a gallery or museum, but you come into a community and you paint murals, you clean lots, you build sculptures. Make art accessible in the community. I think that’s one of the things we need to do, because our schools are in such distress for lack of teachers, lack of teacher diversity, lack of financial support, lack of counselors and equipment and good facilities, you know. They wonder why kids act out. Well you can’t give them facilities that are 100 years old. If the city in cooperation with the unions and other stakeholders could develop a way where art organizations could be incentivized to go into the schools and provide a service….

Creating more teachers, teachers of color and fixing the schools

Allan: Brandywine has talked with the National Art Education Association, their leadership, and one of the things they said is, nationally, classroom art teachers have asked for access to practicing artists. If they can bring a practicing artist into the classroom it will make a tremendous difference. Addressing the issue, there’s a lack of diversity in the faculty. About 85% of American school teachers are female and white.

We’ve got over half a billion public school students in the U.S. And for whatever reason, Blacks, Latinos and Asians don’t even go to school and train to be educators let alone go as visitors into the classroom. You’ve got to qualify first. So, we’re working with Artura.org to, hopefully, at least infuse the curriculum with some diversity in learning, some multiculturalism to help inspire kids. I would like, for example, if the mayor said we’re entertaining proposals for art groups to work with the school district. One project I would like to get funded is to be able to take potential art majors–in 11th and 12th grade–pay them a fee, and they go to Fleisher Art Memorial, Taller Puertorriqueño, Brandywine and other similar organizations on weekends to prepare them for college when there’s no art teachers at their school. To develop a program to expose kids who already know they want to go to art school to think of going to art school to become a certified public school teacher.

Tell young artists about teaching careers

Allan: And how do you do that? Do young artists know that public school teachers make a good wage? They get health benefits; they’ve got a union; they get retirement benefits. Yes, the classroom is stressful, but I contend that if you can walk into that classroom and give them something that they can connect to, that they can relate to, something that comes out of their lived experience, something that connects to their culture, you have a chance fir a rewarding experience all around, then you want to bring artists-educators again into the classroom for diversity. This would also be reflected in improved academic achievement and standardize test scores. The research is there to support this connection.

Give them programs on the weekends, engage in their technology (cellphones)

Allan: My program would pay kids to come on the weekend to learn what professional art education is. They would meet studio-practice artists. They would meet art educators. They would meet current classroom teachers, and talk about the life of an art teacher. And I can tell you–see I taught for 25 years. If you can connect with the kids where they’re at, instead of saying “I’m going to take your cellphones,” it’s “Everybody take out your cell phones and we’re going to take photographs and analyze the photographs and I’m going to tell you how to take a better photograph.” It’s a lesson. You take a picture and, if you have the equipment in the classroom to print that and everybody sends their cellphone photos to a printer and then take that and make artwork out of it. Then you’re engaging in the technology they use, right? But you’ve gotta have a good printer, a good color printer. Because that’s what our kids are being denied all the time, the access to the tools to explore and become excited. Because if you can get a kid to be curious and then go explore you have a chance.

But when kids come in and just blow it off because you give them paint and pencils and colored crayons they’re not going to be turned on. They’ve got TikTok. They’ve got all those tools on their cellphone that one can use. You gotta compete with that. You’ve got to find a way to compete with that. Older youth know the software and tools their smartphone access and use them constantly, but their access and use is not supported by knowing the fundamentals of art What if we could disrupt this backward learning experience, by incorporating smartphones in classroom instruction to a high degree? We could also address the ongoing gap in internet and broad band access affecting home-based learning among poorer households, not to mention maximizing out-of-school instruction and learning.

I can tell you if the city said “Brandywine, we’ve got some money set aside, what do you want to do with it?”, I would say “The pathways to careers in art education.” I would want to work…they’re setting up Bartram and Overbrook and West Philly high schools to be specialized schools where they give employment readiness training. Put some money in that program so that Brandywine and Philadanco, Fleisher Art Memorial, Asian Arts Initiative and all the other serious cultural organization can find a school with a population that connects with what they do and their issues, and go in there and do something and help those teachers who are not as diverse. Get them energized and support them to try innovative approaches.

City-provided insurance coverage for field trips

Allan: Fewer schools are making field-trips to arts organizations and other community organizations. This is for a variety of reasons, often connected to a lack of financial and other available resources (school bus services). And one additional reason is insurance liability if a child gets hurt. Is it the school district’s liability? The organization that’s being visited? A blanket insurance policy funded from the city would solve this. It could cover ALL centers of learning, where this may be a barrier to public access for city schools.There’s so much that can be done, but it needs to be targeted, there have to be some strings attached. That’s what we did with our Visual Artists in Public Service program. We gave artists jobs but they had to go into community centers, into boys and girls clubs, into senior-citizen centers.. They had to use their experience to give a unique and special experience to whoever the constituents were. It’s common sense. Support artists while improving cultural and educational services in communities in need.,

Roberta: We need another program like CETA.

Allan: Brandywine ran a CETA program. We had 38 diverse artists working across the city. Nobody wants to talk about it. It was extremely effective. A new one committed to diversity and engaging with immigrant communities, could support language-diverse artists and populations that are underserved by arts and culture.

Common-sense solutions – Affordable housing for teachers

Allan: I saw a program on CBS this Sunday. It was about a fairly well-off school district in Southern California wanting to make sure they had enough teachers in the classroom. So, anticipating this issue (teachers shortage), which is national now, they built housing for about 140 some teachers. Two-bedroom apartments cost $3,500 on average in this community. So they built the apartments for the teachers to create a subsidized housing program in order to attract teachers. So now, with the salary the school district was paying them they could afford to live there. But if they’re living closer or actually in the community where they teach they take on ownership for the success of that school.

These are common-sense solutions, so it’s not about politics, but using your common sense. And then being able to have something measurable in the end when you ask the group to write what was the impact of what they did. And maybe those impact statements will be fuel for being able to increase the budget or at least keep that in the budget for the future as a tool to attract and maintain well-qualified, diverse faculty, particularly in low-achieving schools.

This crisis intervention is not going to happen, because there’s always going to be a crisis. You have to get at the root cause. It requires compromise, affected parent associations, unions, local leadership, and institutions sitting down with School District leadership and creating a shared plan. Sometimes the root cause solutions take more than four years to happen. It’s beyond your election cycle. You see the problem?

Roberta: Oh yes, it’s called punting it to the next guy. Speaking of next, what’s your next act after Brandywine?

Advising Brandywine, raising an endowment, talking, family and his art

Allan: I’m not going to leave Brandywine. I’m going to be an advisor to the Board. You can’t leave something after 50 years, particularly if you still live in the same city. Brandywine is part of who I am. It’s part of my wife, my daughters, it’s embedded in the Edmunds family. We will always be there to try to support it. One of my goals is to raise money to create an endowment for the Executive Director, cause you always need the leadership to be in a strong position, a stable position, and you can’t recruit on the promise of a salary. You have to have a salary. One of the things smaller groups have real trouble with is thinking about that. If you can raise money, you’d pay current bills. But to be able to raise money to establish something that affects the long-term sustainability, that’s one goal.

I’ll spend more time with my family. I’ve got a grandson now. I’ll spend more time doing my own work. Maybe I’ll do a little writing or something. But I want to be an advocate. I’m enjoying just sitting here telling you. And maybe somebody will read it and say, “Oh, I need to talk to Allan.” And I’ll have the time to talk. But I don’t have the time running Brandywine to just talk. So when I leave Brandywine, after running it on a day-to-day basis, I can have conversations with people so that hopefully I can get inspired to do some of the common-sense things that I just talked about.

Roberta: That’s brilliant.

Allan: That’s a big agenda, right? It’s a big picture agenda. Not worried about the salaries getting paid or the show getting hung or the artist being happy with the work produced. I look forward to that.

Roberta: You’re going to be the philosopher.

Allan: Not philosophy. Strategist. Get people to talk to one another and think strategically.

Roberta: A lot of what you said is like engineering. You’re an engineer in your brain. You’re a builder. You want to build the future for your people. Everybody’s people. And not everybody is doing that.

Allan: They haven’t been blessed to have 50 years like I have. 50 years–that longevity comes with a responsibility. At least I feel that. To share. My staff will tell you, I can’t stop talking.

Roberta: It’s a good thing. You have a lot to share.

Allan: It’s like passing it on.

Roberta: I think talking is a great second act for you. You’ve always been a talker, a really great talker, and philosopher and engineer and sociologist and strategist and all those things. And you should carry on doing more of that. I love that you’re going to have conversations with people.

Allan: I could say big picture items. I know it’s hard for people. It’s been hard for me. But if I were going to try to start Brandywine today it’d be impossible. Things happen in their time. And it’s the right time and there’s been some setbacks along the way but I talk to some of our friends and they say, “You talk like you never left the ‘60s.” The ‘60s is when people really started thinking that they could make a difference and change things. And every time I talk to someone who talks like they’re from the ‘60s we can’t stop talking, because we still believe. We still have hope and faith that things can change. Bad as it is now.

My Board chair, she jacks it up. She’ll say, “Art can change the world.” And I say, “That’s a bold, broad statement, what do you mean by that?” [Pauses] Art can save the world.

Roberta: Well you feel that in your heart. It’s a felt statement.

Allan: It’s the people within the sphere of Brandywine that’s encouraged it. To see what’s happened at Brandywine and know that they were part of it. Being a part of something bigger than yourself. My pastor told me one time–I told him I couldn’t give as much time as I wanted to the church. He said, “I understand, Edmunds, you have your ministries.” He let me off the hook [Laughs]. I never looked at it that way.

Roberta: Oh yeah, you’re a preacher.

Allan: No I’m not a preacher. I’m an average person who works way too hard.