“Modigliani Up Close” at the Barnes Foundation through January 29, 2023 is a gem of an exhibition. Forty-two paintings and eight sculptures, borrowed from major international museums and private collections, build upon the Barnes’ significant collection of the artist’s work (twelve paintings, one sculpture, and three works on paper) and highlight Albert Barnes’ interest in demonstrating the influence of African sculpture on Western modernism. Modigliani’s work has been slighted by art historians, perhaps due to the conventionality of his subject matter, and possibly in reaction to the inexplicable attraction of his palette and brushwork and the timeless interiority and classicism of the sculpture. The exhibition is an opportunity to indulge in the seduction of his work.

The artist’s biography lends itself to a Hollywood treatment–indeed two films have been made and a third is in the works. Modigliani was a handsome, young artist from a well-established Jewish family in Livorno. To escape an academic education and his provincial background, he moved to Paris in 1906, where he met Brancusi and Picasso. After becoming part of this international circle of European expatriate artists, he cultivated a bohemian lifestyle which included the consumption of a great deal of alcohol and drugs. This may have been an attempt to self medicate, or to disguise the tuberculosis which plagued him since childhood and would eventually kill him at the age of thirty-five. A pregnant fiancée who flung herself from a fifth-floor window the day after his death only adds to the melodrama.

1963.2.16 / MAC USP Collection [Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP Collection, São Paulo, Brazil]

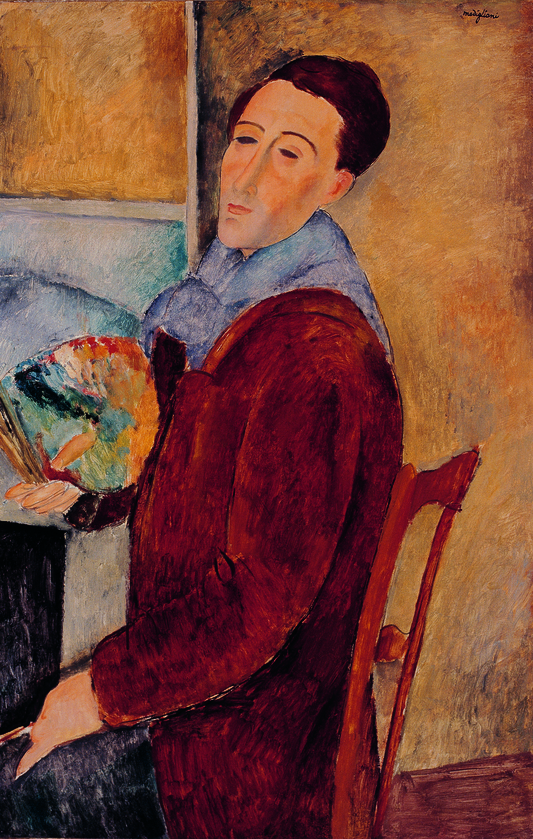

Modigliani developed a style that involved attenuation and abstraction of the human face and figure, yet was able to represent a wide range of highly individualized sitters. We can judge his ability to capture their likenesses from the many portraits of his artist friends which can be compared to photographs: he painted Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Diego Rivera, Chaim Soutine, Suzanne Valadon, and Jacques Lipschitz, among others. His least accurate depiction may be the self portrait that opens the exhibition showing the artist sitting at an easel, palette in hand, with a mild expression and the attenuated figure and face that he favored in his work. Yet in photographs the artist’s face is consistently broad and his expression intense.

Modigliani’s sculpture was made during a limited period and is well represented in the exhibition by eight works, all heads and, with one exception, all variations on an elongated, abstracted ideal. He was self-taught in sculpture, and like many artists who worked in the long shadow of Rodin, who was a modeler, he turned to direct carving. The heads are arranged in a circle here, which is likely a reference to the fact that the artist exhibited seven sculptures in the Salon d’Atonme in 1912 and arranged them as an ensemble, in a half-circle, implying that they were more than a number of individual works. Friends of the artist noted that he placed lighted candles on the heads when they were shown at his studio. This evokes the kind of work made for ritual use, where recognizable subject matter is more important than either uniqueness or individuality of the artist’s vision. While Albert Barnes clearly saw references to African sculpture in Modigliani’s sculpture, they also suggest Cycladic, Etruscan, Greek, and Cambodian art, as well as Indian temple sculpture, since many of the heads imply that they were integral to architecture, with unfinished backs and tops.

The exhibition emphasizes new research on Modigliani’s technique, for both the sculpture and paintings, and the labels discuss research methods and findings. They give viewers a good idea of the methodology of such studies in general, as well as providing information specific to the work on view. It turns out that the artist reworked canvases – both his own and those of others. It is not uncommon for struggling artists to reuse canvases, although when they wish to hide this fact they usually sand them down. Modigliani seemed to have found inspiration in both the colors as well as the textural effects of the previous paintings, both of which he incorporated into his work. His palette changed throughout his career, which in part reflected a change in the color of grounds (the painted priming covering the canvas). He employed a variable style of paintwork, even within a single work, and his use of textured paint rarely suggests the surfaces he represents. This is particularly clear in the nudes, where he uses both highly textured paint on part of the figure and smooth texture elsewhere.

“Modigliani Up Close” is the result of research collaboration by the conservators and curators who organized it: Barbara Buckley, Senior Director of Conservation and Chief Conservator of Paintings, and Nancy Ireson, Deputy Director for Collections and Exhibitions and Gund Family Chief Curator – both at the Barnes – as well as Simonetta Fraquelli, Independent Curator and Consulting Curator for the Barnes, and Annette King, Paintings conservator at Tate, London. Fifty colleagues from lending institutions also contributed research, making the catalog a significant resource on the artist.