Part 1

Barbara Bloemink, “Florine Stettheimer; a biography” (2022)

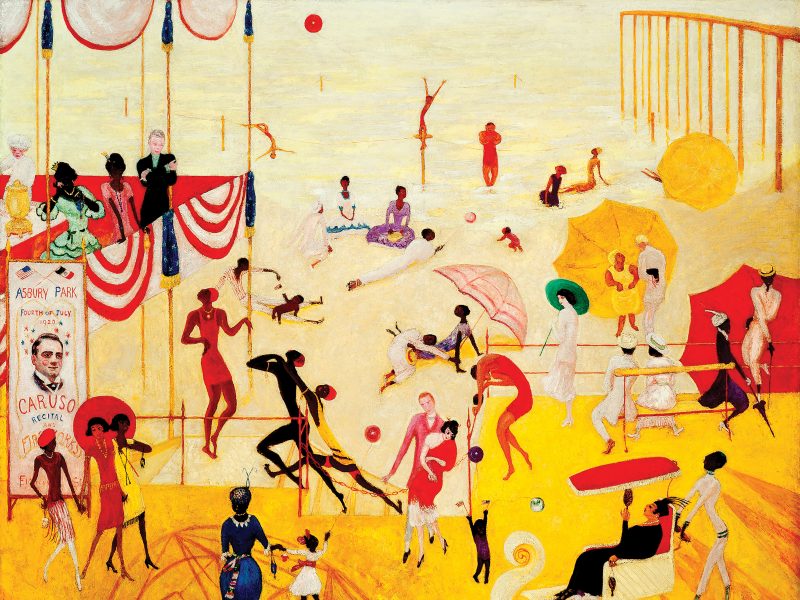

Florine Stettheimer has a largely underground reputation and her achievements have been generally misunderstood. Barbara Bloemink has published more than anyone on the artist, and her recent research has changed her own understanding. Stettheimer is regularly described as an amateur who was most significant as hostess to a group of avant garde artists in New York in the 1920s. She and her two sisters ran a salon for artists, critics and writers, whose most prominent member was Marcel Duchamp.

From Barbara Bloemink, “Florine Stettheimer; a biography.” Hirmer Verlag Gmb H (Munich: 2021) ISBN 978-3-7774-3834-4. Courtesy of Hirmer Publishing and Alexandra Fanning Communications.

If amateur status is defined solely by lack of sales, one could plausibly use it for Stettheimer. Bloemink demonstrates, however, that she had a proper, academic art training in Berlin, four years’ study at the Art Students League, and considerably more first-hand knowledge of European old master and contemporary art than any of her American, modernist colleagues. Illustrations of her early work, included here, make it clear that her later rejection of academic conventions of drawing, perspective, relative scale and traditional art world taste was a sophisticated and intentional choice. Stettheimer exhibited across the U.S. and in Paris, was invited to join more than one of New York’s most prestigious galleries, and generally received positive attention in the art press. Her preference not to sell her work was based on her hope that it might end up, in its entirety, in a museum.

This biography situates Stettheimer as an educated, independent woman who took efforts to create and maintain her artistic reputation. Bloemink will surprise readers when she describes Stettheimer as an early feminist whose paintings included sexual, racial and political subjects. The book is very beautifully designed and printed, with a wealth of color illustrations of artwork and photographs of the extravagantly-decorated living and working environment where Stettheimer exhibited her paintings to a select audience. It will be welcomed by anyone interested in American modernism, the art scene in New York in the 1920s and 30s, and American women’s history.

Barbara Bloemink, “Florine Stettheimer; a biography.” Hirmer Verlag Gmb H (Munich: 2021) ISBN 978-3-7774-3834-4. U Chicago Press | Barnes & Noble

Brian Alfred, “Why I Make Art; Contemporary artists’ stories about life and work” (2022)

In 2016, the artist Brian Alfred began podcasting conversations with artists, mostly his friends. After the pandemic he switched to interviews via Zoom, which considerably broadened the pool of artists. This book draws from from thirty podcasts and very much retains the sense of conversations among working artists. All have managed successful careers, although few are household names. The volume includes color reproductions of one or more works by each artist, which gives significant context for their discussions.

The conversations emphasize the artists’ early decisions to pursue art and what keeps them going. While James Sienna talks about an early day job cutting mats, this is not a book about the practicalities of artists’ lives. While it is not intended to offer models for younger artists, the book will certainly interest them, as well as anyone who has wondered what it means to be an artist today.

Painter Inka Essenhigh talks about the challenge of aging and producing work that may not fit easily into current discussions around art. She believes that her fantasy-inspired imagery can open people’s minds to a different future. She is interested in change, not escapism, and is clear about her ambitions to produce works that move her viewers emotionally, even if they don’t experience or understand them as the artist does. Multi-media artist Kahlil Robert Irving speaks of the significance of the art he has seen in museums, mentors, and his study and travel abroad, which gave him “…so much life and breath to see the length at which human existence is going, the fact that there is such a broad swath of life.” [Ed. Note: Kahlil Robert Irving was featured in the recently-closed exhibit, “New Typologies” at the Philadelphia Art Alliance. See Roberta’s review for more.]

vanessa german [intentionally lowercase], who works in performance and visual art in many media, talks about scale — not physical scale but the scale of ideas: “… the grandest scale that I can find to occupy the ideas was … my entire life and my relationships with other human beings and my relationship with the invisible worlds – the world of soul and spirit, and magic – and the world of everyday making….” She asked herself “What does it actually mean for me to believe in art in a way that comes unraveled from any sloganeering? … to live and be alive in that which you believe in?” She began to work with her neighborhood, first with anyone who joined her on her front porch, then setting up theARThouse as a community hub.

Brian Alfred “Why I Make Art; Contemporary artists’ stories about life and work.” Atelier Éditions (Los Angeles, 2022) ISBN 978-1-7336220-9-7. Atelier Editions | Artbook

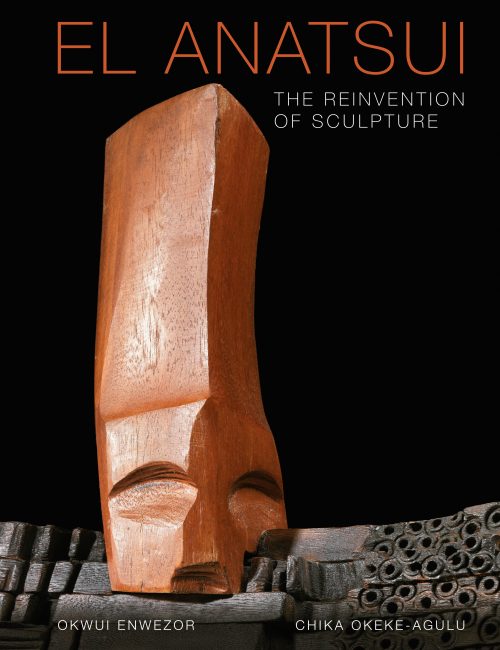

Okwui Enwezor and Chika Okeke-Agulu “El Anatsui; The reinvention of sculpture” (2022)

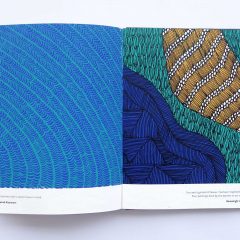

This splendidly-written and produced volume offers the most significant assessment of the work of a major and singular artist. El Anatsui’s artwork is clearly identifiable, powerful and visually seductive; he recycles the lowliest of industrial waste into art of startling beauty. Born and educated in Ghana, Anatsui taught at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka from 1975 until his retirement in 2015. Both authors are Nigerian and were committed to situating the artist’s work in an African context; this includes complex questions around post-colonial independence and earlier 20th century ideas of Négritude.

The authors address the politics of form for Africans who rejected or significantly altered European conventions as well as the use of materials that carry meaning. Chapters address three, key themes: “Aesthetic and Rhetoric of Fragmentation,” “Metamorphic Form,” and “Epic and Triumphant Scale.” They trace Anatsui’s use of fragmentation to his knowledge of African material history as fragments, social fragmentation of post-colonial Ghana, and series of muti-part works culminating in a technique that evokes its own construction and the possibility of decay.

Anatsui’s mesh, hanging works offer no installation instructions; it is entirely up to the owners, curators and art handlers to decide which side is the top, at what height and angle a work will be hung, where the mesh panels will be bunched, crumpled, and folded and whether the wall-based work will extend onto the floor. What any viewer knows of a work – in the original or in reproduction – depends entirely upon where it was installed – hence, what the authors term “metamorphic form.” This is an unprecedented concept modern sculpture. The work has never been stretched flat against the wall, as large textiles are displayed; while the artist was influenced by the modular designs of West African textiles, he always conceived his work as sculpture. The authors also situate Anatsui’s contingent forms that are based upon communal activity within philosophical traditions of West Africa and his experience of ritual objects which change with repeated use.

This book is extremely sensitively conceived, designed and produced, with a wealth of photographs, including multiple views of three-dimensional installations and multiple iterations of works that varied with installation site. It will be greatly appreciated by all readers interested in contemporary art as well as those who have been looking for discussions of contemporary art produced beyond the Euro-American context that address the implications of local history, ideas, materials, traditions, and post-colonial experience.

Okwui Enwezor and Chika Okeke-Agulu, “El Anatsui; The reinvention of sculpture” (2022). ISBN 978-88–6208–763–6. Artbook | New Museum Store