Fleisher/Ollman’s current exhibition, on view until January 7, brings together six artists and more than one hundred drawings but takes its name from a single work: Leigh Bowery & A Bottle of 7UP, a vivid colored pencil and graphite drawing by Anthony Coleman that faces the entrance to the gallery. Of the six artists on view, Coleman is the biggest name—his solo show at Marvin Gardens, which opened last month, was a critics’ pick at Artforum—but there are good reasons for building this exhibition around his eponymous drawing that have nothing to do with publicity.

Leigh Bowery & A Bottle of 7UP takes the colors, ideas and visual motifs on the surrounding walls and condenses them into one image. Two angular forms, rendered in graphite and colored pencil, stand out against a yellow background in an oddly magnetic pairing. On the left is the bottle of 7UP, which is immediately recognizable for its logo and green color, but not necessarily its shape, which is more like a pint glass sitting on a basketball. To the right of the bottle, and distinguished by a polka-dotted shirt and thick makeup, is Leigh Bowery, the performance artist and designer who posed for Lucien Freud and worked with Vivenne Westwood.

Like many of the figures in Coleman’s drawings, Bowery has a long, knobby nose—a distortion, but with none of the derisiveness of the amusement park caricatures. Instead of mocking his subjects, which are often cartoon characters or brand mascots, Coleman seems to love them, identifying and then riffing on closely observed details of their design.

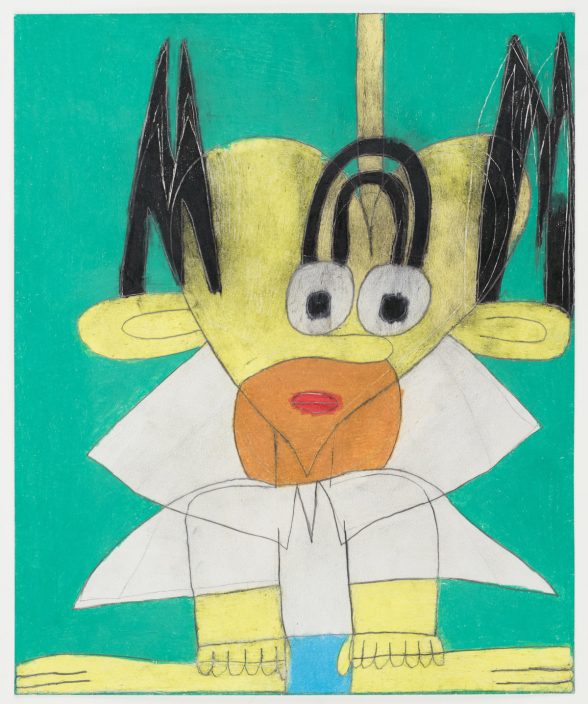

In one drawing, the M- and upside-down U-shapes of Homer Simpson’s hair become several times larger and jump from his yellow head. His distinctive five o’clock shadow spills across his shirt, and his collar unfolds into a pair of wings. In another, Coleman gives Spongebob massive lash extensions that somehow feel more true to the character than the original design. Nearby, Coleman reduces Garfield’s tabby coat to two black triangles on a blocky orange body, but a pair of sleepy eyes make the character immediately identifiable.

Coleman’s drawings approximate the kind of image that forms when you try to recall something—a logo, a mascot—that you’ve seen thousands of times in magazines and in social media feeds but don’t have in front of you. It is the strange aesthetic experience of a world saturated with mass-produced media: certain shapes and colors are imprinted vividly, but other things, like the proportions between design elements, are lost entirely.

Every artist in the show engages in some way with this idea of representation in the age of digital media. Most of Chantal Bobo Peden’s drawings, on display next to Coleman’s, are of unnamed figures and geometric abstractions, and all are composed of stained glass-like panels that are meticulously shaded with brightly colored markers. Two have specific pop cultural subjects: Rihanna and Girlfriends, which depicts three characters from the sitcom of the same name. Another, Untitled (fashion), superimposes a line drawing of a face along with the word FASHION on a colorful paneled background.

For Jennifer Williams, whose work is on display in the next room, fashion is an obsession. Her ballpoint pen drawings, which have titles like Supermodels on the Red Carpet for Ralph Lauren and Models from London, are variations on a theme. Like magnetic dress-up toys, Williams’ figures begin with the same base and are distinguished by their haircuts, their dresses, their accessories. In her beautiful portrait of Frida Kahlo, for example, thick braided hair and a unibrow identify the subject. Williams shares Coleman’s inclination for making loving caricatures, for isolating the essence of a character or, in fashion, a certain look. She also has an inclination for specifics. Some supermodels are walking for Ralph Lauren, some are from London. Other models are identified by name: Beverly Johnson, Theresa Randle.

Christian Hayes’ drawings, which are in the same room as Williams’, are similarly attuned to details, but his visual fixations are different. Instead of the red carpet, it’s the Philadelphia 76ers (Hayes is a fan) and Chuck E. Cheese (he works there part-time). Many of his drawings include portraits of Sixers players with their names underneath, the kinds of images that appear on TV broadcasts and megatrons at the start of every game. (The players’ jerseys notably include the logo of Crypto.com, a cryptocurrency exchange and team sponsor.) Interspersed with Sixers players and Sixers logos are other pop cultural artifacts—Elsa from Frozen, Spongebob flipping burgers, the Chuck E. Cheese mouse. Hayes doesn’t process hyper exposure through caricature; instead he reproduces fonts, logos, and characters with precision and collages them, simulating the kind of jumbled aesthetic experience that digital media produces.

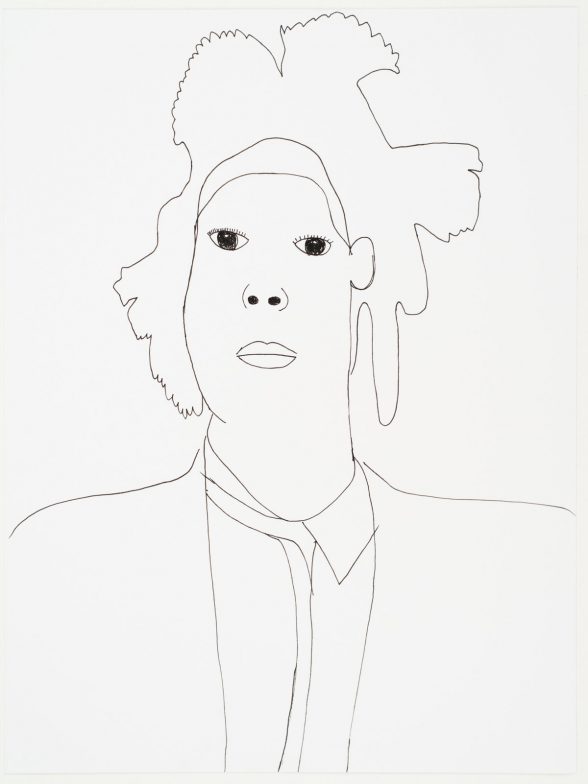

Across the room, Bayaht Ham’s beautiful, spare pen drawings also find their inspiration in popular media and advertising. One depicts the cast of Star Trek: Next Generation, and another is a mob of Nintendo characters. There are Gucci models and Tiffany lamps, too. In Ham’s drawings, though, the brands and pop culture iconographies are merely raw materials—means to an end. The goal, evident in pieces like Jean-Michel Basquiat and James Baldwin Dancing, is a graceful economy of line.

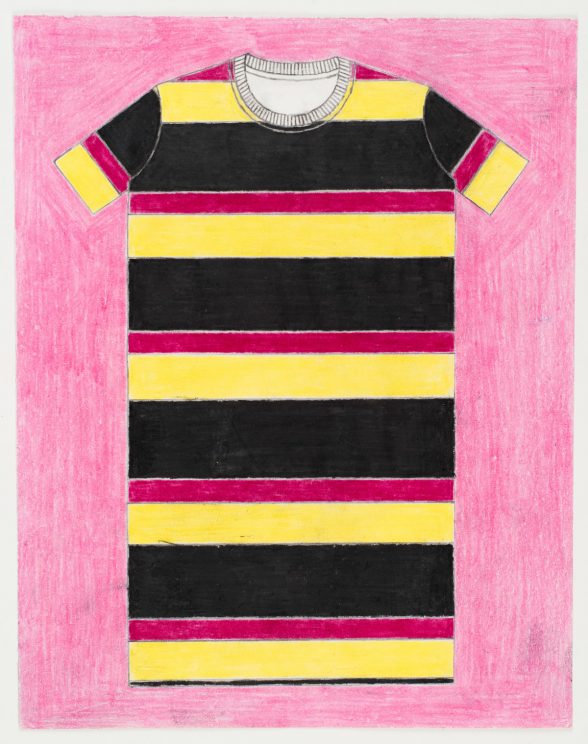

There are no logos or cartoon characters or fashion brands in Woodley White’s drawings. There are only objects, repeated again and again with variations in color, perspective and dimension. White is best known for his drawings of t-shirts; earlier this month he opened a solo show at Summertime Gallery in Brooklyn called Ode to the Tee. Where the other artists in Leigh Bowery & A Bottle of 7UP use repetition and reproduction to engage with mass media, White applies the same pop-art tools to mass-produced design objects, searching for, and coming perilously close to discovering, what makes a shirt a shirt or a subway seat a subway seat. The strong graphite lines and vivid colors are arresting; Untitled (black patterned shirt 1), striped with repeating sequences of diamonds and battlements, is very nearly hypnotic. White’s cryptic signature, a neat line of plus-signs, runs across the bottom of some of the drawings like printer’s marks, confusing the distinction between originals and copies.

The six artists in Leigh Bowery & A Bottle of 7UP, which is on view until January 7, are united by shared visual languages and thematic interests. They also happen to work with the same program, Artworks, a constellation of studios across the city staffed by a team of working artists and run by Community Integrated Services, an employment organization that supports people with disabilities. The artists receive assistance with things like materials and professional development, but they are creatively and financially independent.

Alex Baker, director at Fleisher/Ollman, has worked with similar organizations in the past, like Arts Project Australia, in Melbourne. He said that the art world “lacks an engagement with what self-taught art might mean in the 21st Century,” a gap that Fleisher/Ollman is trying to bridge by “exhibiting work by living artists from developmentally disabled studio programs,” according to the gallery’s website. Doing so involves a difficult negotiation between an ideal future, in which art is accessible and the various abilities and disabilities of artists are irrelevant, and an imperfect present where barriers to entry make the work of organizations like CIS essential.

“The danger implicit in all of it is the walling-off,” Baker said. “We didn’t want to showcase the fact that the artists have disabilities, but we also wanted to recognize the program.”

Eli VandenBerg, manager of employment services at CIS, prefers that his organization remain mostly behind the scenes. The attention should rightfully be on the artists and their artwork, which needs no qualification. “I don’t know how much we should be thanked for opening a door that shouldn’t have been locked in the first place,” VandenBerg told me in an email. “I believe we are most successful when no one knows we exist.”