You might not expect an intergenerational group exhibition of bluechip abstract artists representing solid work in a wide range of media to be found in Harrisburg, PA. But you would be wrong. Any such assumption is instantly dispelled upon entering the Susquehanna Art Museum in downtown Harrisburg, where you’ll find Shifting Forms: 5 Decades of Abstraction, a fresh perspective on the enduring tradition of non-objective art—one more intimate and less bombastic than what you might associate with the genre.

Courtesy of the Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University

Two more different abstract pieces could not be found paired together than “Parrot Jungle” (1981) by Helen Frankenthaler and “Ten Blocks West” (2005) by Chakaia Booker, two works that demonstrate the breadth of abstract art both in terms of form and materials. Frankenthaler’s painting, which is familiar but not exactly typical of the late abstract expressionist, consists of thick daubs of colorful acrylic paint applied by the artist in select areas over washes of green and blue that suggest an oblique view of a landscape. “Parrot Jungle” hints at Frankenthaler’s earlier career, but this more mature composition feels fresher, more free, and somehow softer than her earlier work. In fact, the show as a whole feels softer, more understated than the usual brash machismo often associated with abstract art.

“Ten Blocks West” (2005), by contrast, is wall-hanging assemblage consisting of the remnants of different-sized rubber tires which twist and turn with snakelike contortions. As the wall text explains, Booker has been using the rubber from old tires as her primary medium since the 1990s, both because of its durability and because of its historical associations with colonialism and environmental concerns. The wear and tear upon the rubber further suggests the effects of aging on human skin, while the patterns on the tires’ treads recall those of African scarification and textile designs.

Sol Lewitt who, along with Frankenthaler, is one of the more prominent artists on view in Shifting Forms. As with Frankenthaler’s “Parrot Jungle,” his “Vertical Lines Not Touching (Black)” (1971) is more humble than what the postwar conceptual artist is known for, if not in form then in scale. The modestly-sized picture displays just what its title describes: thousands of discreet, pencil-thin, vertical white lines not touching and filling a black void, creating a soft fuzziness, like static on a TV screen, or heavy rain falling in the night sky.

Helen Frankenthaler (1928 – 2011), “Parrot Jungle,” 1981, acrylic on canvas

Collection of Marty and Tom Philips

Chakaia Booker, “Ten Blocks West,” 2005, rubber tires and wood

Courtesy of the Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University

Sol LeWitt, “Vertical Lines Not Touching (Black),” 1971, lithograph on paper

Courtesy of Lehigh University Art Galleries

Helen Frankenthaler (1928 – 2011), “Aspens,” 1991, acrylic on canvas

Collection of Marty and Tom Philips. Photo: Bonnie Mae Carrow

Works by women artists abound in this eye-opening exhibition. Alice Trumbull Mason, for example, was an early leading figure of the American Abstract Artists in New York City, and an important pioneer of American abstraction. Her “Magnitude of Regions” (1962) is a “hard-edge” picture that weaves together bright colors with isosceles triangles defined by sharp diagonals that push and pull your focus across the picture plane. The overall effect of this work transcends its modest size.

Nearby, “Untitled (Lincoln Center Print)” (1980) by the late interdisciplinary artist Nancy Graves is informed by the data points and other mediation of natural phenomena such as the many moon and weather maps produced by NASA. The basic patterns in the lively screen print are culled from these documents by Graves who transforms them into playful, vibrant abstractions that complicate and eclipse her source material.

Other prints in the exhibit further point to the range of media used by artists practicing abstract art. For example, two offset lithographs by Bruce Conner, the late postwar abstract artist known for evading simple classification by continuously altering his materials and modes of art making over the course of his long career. The black and white, double-hung prints on view in Shifting Forms, “#113” and “#208” (both from 1970), consist of concentric circular forms that ripple outward, quietly floating in their respective frames. Both prints have an almost cellular quality to them, as if they were scientific renderings of osmosis.

But painting is what people generally think of when they think of abstract art. And painting is the most consistent medium on view in the exhibition, even when it’s combined with other media like screenprinting. Take “Open Screen (Dance Machine)” (2022) by Benjamin Lee Sperry. Two large, equally-sized pictures made of acrylic paint laid over a generic, commercial fabric hang side-by-side. The machine-made patterns of the purplish material commingle with the more gestural marks rendered in bright paint: repeatability and randomness share equal space in this diptych that almost appears to be the same composition twice. But there are enough differences between the two for the eye to alternate between them and discern their likenesses while delighting in their difference.

And don’t miss Philadelphia artist

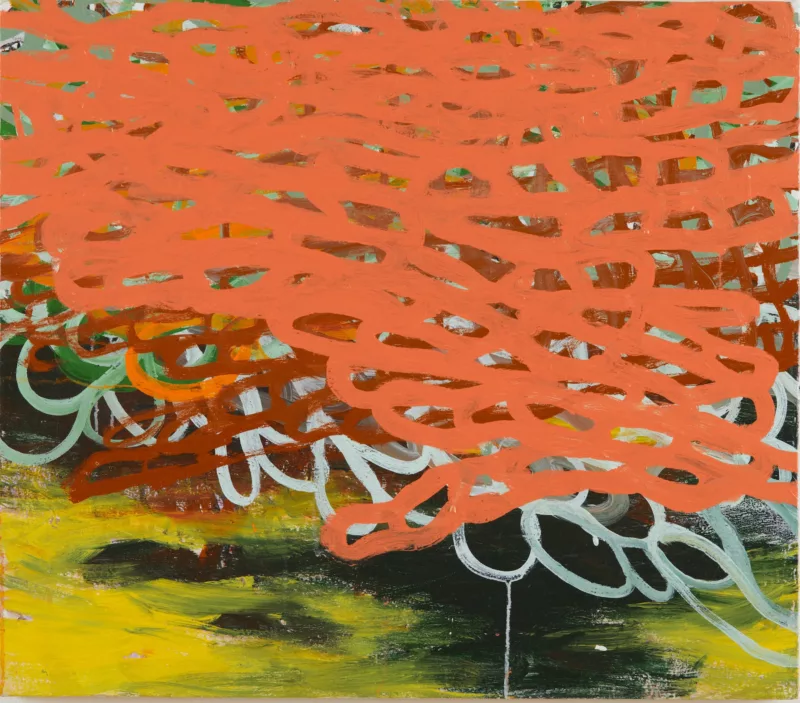

Tim McFarlane’s “Undercurrent” (2007). As the title suggests, there are several gradations of acrylic paint to this work. A yellowish-green underpainting is mostly obscured by progressive strata of curlicue brushstrokes in light blue, crimson, and bright orange. Each successive layer of paint applied by the artist intimates multiple modes of execution, as if McFarlane kept reconsidering the ultimate configuration “Undercurrent” would take. The final product provides you with a geology of thought and an accumulation of imagination.

The largest and perhaps most elaborate piece in the show is “The Greens” (2019) by Jonathan VanDyke, a New York City-based artist originally from Hershey, PA. A tall, metal structure serves as an armature for the painting part of the piece, a gridwork of hexagonal patterns made of water-based paints and dyes applied to sewn fragments of cotton T-shirts, denim, and trouser fabrics. You are allowed to walk behind the scaffolding of “The Greens” to take a closer look of its obverse. This behind-the-scenes vantage permits you to examine VanDyke’s process of meticulously sewing together each stained piece of fabric while literally standing inside his work.

Tim McFarlane, “Undercurrent, “2007, acrylic on canvas

Courtesy of the Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University

Bruce Conner, “#126,” 1971, offset lithograph on paper

Courtesy of the Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University

Bruce Conner, “#208,” 1970, offset lithograph on paper

Courtesy of the Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University

Bruce Conner, “#113,” 1970, offset lithograph on paper

Courtesy of the Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University

Jonathan VanDyke, “The Greens,” 2019, ink and water-based paints and dye on cotton t-shirt, denim, and trouser fabric, backed with dyed linen. Photo: Bonnie Mae Carrow

Equally large, and also engaging with fabric — quilts the artist helped to produce during her years as a textile designer in New York City after fleeing Nazi Germany in the 1940 s— is “Schoolmaster, Echo, and Hen” (1983) by Beatrice Riese. This tall oil on linen abstraction is a geometric work of art similar to Alice Trumbull Mason in its hard-edged approach. The variations within each square unit of the grid—from playful zig-zags to rectilinear bands of muted colors—invite you to move in close to the piece for careful inspection while also inspiring you to step back now and then to take in the complete painting. Indeed, the show as a whole invites you to move in close to appreciate the details of each work, while also stepping back to take in the bigger picture that is the long, robust history of abstract art.

Cities too have long and storied histories. Going to view Shifting Forms: 5 Decades of Abstraction introduced me to both the Susquehanna Art Museum and the City of Harrisburg. I am based in Baltimore, which, like Harrisburg, is an aging post-industrial, “Rust Belt” city which has seen better days. The decaying infrastructure of Harrisburg reminded me of my homebase. Yet, like Baltimore, Harrisburg is full of beautiful art and architecture, and rich in culture and history. Pennsylvania’s radiant Beaux-Arts-style statehouse is only a few blocks away from the Museum. As with similar experiences I’ve had in Baltimore, it was edifying to find an excellent art exhibition representing a wide range of talented artists in such a place, a diamond in the rough as it were.

Whether you live in the Harrisburg-Carlisle metro area or are further afield in the Susquehanna River Valley (or even out-of-state), and would like to experience a new take on the ever-evolving history of non-representational art, then check out Shifting Forms: 5 Decades of Abstraction at the Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg, PA. You will not be disappointed.

Shifting Forms: 5 Decades of Abstraction will be on view through Sunday, January 21. There will be an exhibition tour and artist talk open to the public on Friday, December 1, from 5:30-7:00 PM.

The Susquehanna Art Museum, 1401 North 3rd Street, Harrisburg, PA, 17102