Wanderlife Gallery, located at 2231 South 13th St. has been in South Philadelphia since 2018. It is a small and professional space for the exhibition and presentation of analog photographic art. During the pandemic the gallery was on a pause like most of the arts organizations throughout Philadelphia. It reopened with the rest of the city and has had a string of exhibitions, artist talks, and spoken word events. It is currently featuring Ahmed Salvador and Scott McMahon in an engaging exhibition up through December 2nd. Entitled “Home and Other Stations” and “Sight (Unseen),” both artists use alternative photographic processes in their practices. Salvador is based in Philadelphia, has shown locally, and teaches traditional photography at Fleisher Art Memorial. McMahon received his BFA from University of the Arts in Philadelphia and is now based in Missouri.

The alternative photography scene is a vibrant, widespread community of practitioners. Within that community there are a variety of definitions as to what alternative photography encompasses, but it generally refers to a range of photographic processes that are not commonly used in modern photography. These processes include things like pinhole cameras, cyanotypes, tintypes, chemigrams, platinum prints and quite a few more. In 2015 the J. Paul Getty Museum sought to amplify this field with a major presentation, Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography. The exhibition, which I saw, included seven artists and their alternative approaches to analog and digital photography. They shared a desire to explore photography’s essential materials, focusing their investigations on light sensitivity and how light interacts with different chemical processes on a range of photographic papers. A few of the photographers built elaborate cameras that were unique. What the exhibition also underscored is how photography from its beginnings in the mid-19th century has been shaped by experimentation, the spirit of invention, and discovery. The artists in the Getty Museum exhibit clearly loved alternative processes and the visual possibilities it afforded them. They were seeking different approaches to understanding photography as a medium.

You can see this same love of invention and discovery in the photography at Wanderlife Gallery. Ahmed Salvador and Scott McMahon know each other and have been collaborating long distance. It is a productive and flourishing professional relationship. For example, in one project they mailed pieces of unexposed film or photographic paper back and forth, intentionally letting some light get into the packages. When they received the packages, they printed the unexpected results and then returned them. A version of this project was written about by Chip Schwartz in Artblog in 2012, when Salvador and McMahon presented their work at The Light Room Gallery.

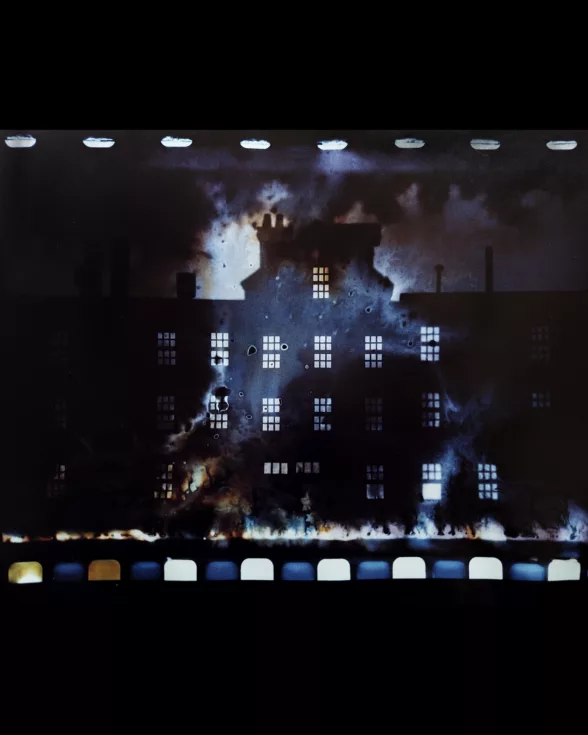

Salvador’s “Home and Other Stations” at Wanderlife is a series of small prints. The prints retain the appearance of a section of enlarged 35mm film, the film sprockets framing images of buildings and landscapes floating in overexposed and underexposed space. Salvador describes his printing methodology as a ‘RA-4 reversal wet process chromogenic print and the end result a unique photogram utilizing a miniature and two superimposed chemigrams done on 35mm film.’ RA4 reversal is a photographic technique that involves using color paper to produce positive images instead of negative ones. Color paper is normally used to print color negatives, but in RA4 reversal, the paper is either exposed directly in a camera or printed from slides. To then get to what Salvador produces involves numerous steps. It is complicated, and requires a chemist’s knowledge of the darkroom. And that is the fun and magic of his alternative photographic work, employing the alchemy to come up with unanticipated results. Some of Salvador’s images are reminiscent of Sally Mann’s 2008 landscapes from her Blackwater series. Other images depict disembodied buildings that suggest the photographers Hilla and Bernd Becher. These references are meant to put Salvador’s work in a lineage of sorts, and are a compliment. His work is delicate, colorful, and conveys a nostalgia about home, place, memory, and our tenuous grasp of it.

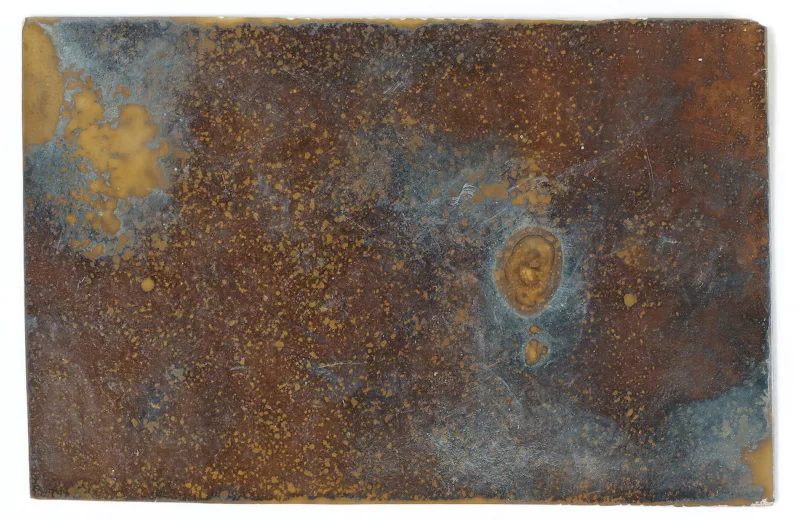

One of the early artists who experimented with chemigrams was the Swedish playwright August Strindberg. In 1893 he laid a series of light sensitive photographic plates on the ground and attempted to capture images of the night sky. He named the technique celestography, later known as chemigrams. At first, Strindberg thought his images were successful: galaxies took shape, clouds, astronomical and meteorological phenomena seemed to appear. Looking at them now, they could have had the appearance of early Hubble Telescope imagery. But in reality the images resulted from chemicals mixing with photosensitive emulsions and other particles, such as drops of dirt and dust. Instead, the work is some of the first abstract photography, as Strindberg heralded 20th century artmaking with his belief in “chance in artistic creation.”

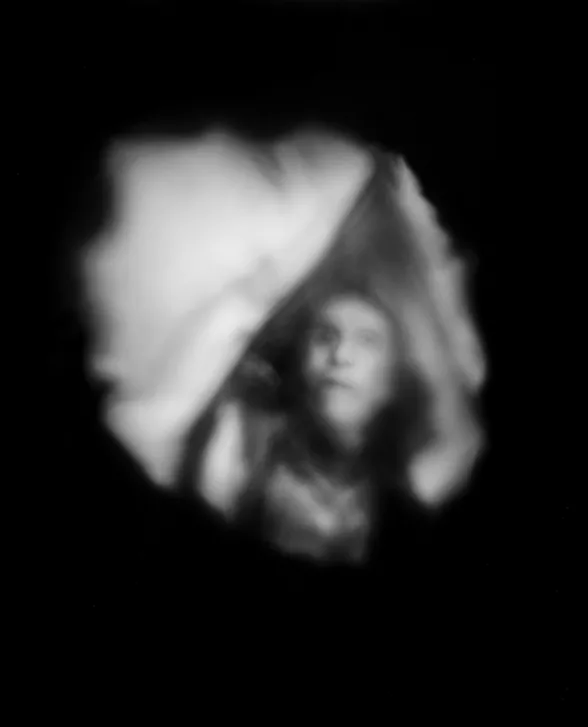

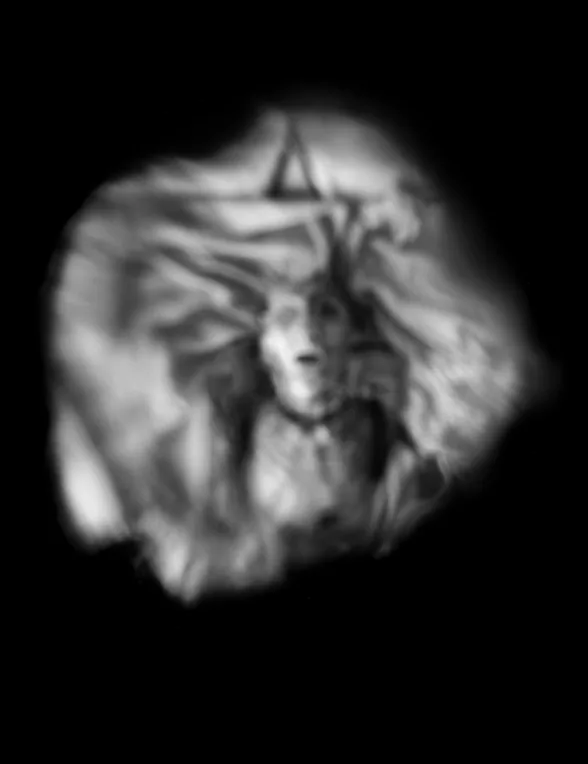

There is a tremendous amount of chance in what happens in alternative photography. Salvador’s photography, working with the dynamic of chance, is very much akin to what Strindberg spoke about when he may have inadvertently helped to invent alternative photography. Years ago, Scott McMahon saw one of Strindberg’s photographs in a magazine named Pinhole Journal. The image had been taken using the lens from the eye of a beetle to make a landscape photograph. Remembering this, McMahon approached his project “Sight (Un)Seen” experimenting with a homemade pinhole camera. Reasoning that since the camera lens is designed to resemble a human lens, for Sight (Un)Seen he would literally use human lenses that came from cadavers. He received permission from the families of the donor cadavers to take the lenses from the eyes of the deceased and placed them in a pinhole camera. Pinhole photography is simple; light-sensitive black and white photographic enlarging paper receives a projected image. Upon chemical development, a photographic negative is produced and then a positive print is made.

Gallery and the artist

McMahon’s photographs in “Sight (Un)Seen” are disorienting, as perhaps Strindberg’s were when first viewed. Many of the photographs on exhibition at Wanderlife are portraits of the cadavers, taken with their own lenses. The images are hazy, silvery, ghost-like images floating on deep black backgrounds. The uneasy idea arises that this is the last image the deceased was seeing as it leaves this worldly plane. Reality is inverted somehow, and it is unsettling. The images are vaguely familiar in appearance to Victorian spirit or ghost photography. McMahon also displays photographs of living persons, landscapes, and architecture, but it is the portraits of the cadavers that are captivating. For the artist, it is “true collaboration between art and science, the living and the deceased. The viewer, at times may be left with questions and some ambiguity, which I believe fuels art that is compelling and thought-provoking.”

This December Wanderlife Gallery is having their annual REMIX call for art. In collaboration with Gaby Heit Art+Design, they ask artists to submit work displayed in CD cases. It’s like a tribute to defunct media, and will include the Media Museum on display in the gallery, which is a collection of old cameras and tech. In addition, the gallery will fill the space with CD’s and tapes for sale for $1. Here’s the call for art for REMIX

Wanderlife Gallery’s first exhibition of 2024, Haunting Beauty, will feature photographers Dafna Sternberg and Elizabeth Kelly. The opening reception is February 2, from 6:00 to 9:00PM.

More about the gallery

Wanderlife founder, Beth Ann, says the mission of the for profit gallery is to ‘revive and popularize the use of historic photographic and print processes like cyanotype, gum bichromate, daguerreotype, photogravure, liquid emulsions and film/darkroom photography, which is the newest technique to join the alternative process lexicon; to exemplify the connection between visual art and the written word; and to convey the impact of place in the creative process.”