Art Disease

In my studio art class at Brown University in the late 1970s, Robert Motherwell came in one day to give a talk about art and life to about a dozen of us undergraduates. He sat down, promptly lit a cigarette, took a drag and began to regale us about his days in 1940s Paris with Picasso and other illustrious art gods. As he spoke, his cigarette slowly morphed into an ashen arc, of which he seemed oblivious. Suddenly, we were all on the edges of our chairs, studying this weird comic performance. It elicited enormous tension. Waiting for the ash to drop! Would Robert Motherwell, one of the key authors of Abstract Expressionism, toss his cigarette to the floor or take another drag, as the ashes drop into his crotch? He was a myth, Motherwell. Cool, successful, and present. I remember the cigarette ash arc, but not what Motherwell did. I do, however, remember the question and answer session that followed.

We peppered the great artist with questions about the check Picasso paid lunch with (that was never cashed), how he organized the plates and glasses and saucers on the table, and all about Motherwell’s own studio where he produced his Elegy series or his magical blue collages out of torn Gauloise cigarette packages. More pertinently, I asked him about his failures. What did he do with the work he felt didn’t quite measure up? Robert Motherwell’s bad paintings? His mistakes?

“Well,” he said, “I have a furnace in my studio. I typically … burn them.” Really? I found this hard believe. Even Motherwell’s mistakes were more valuable, I thought—actually, I knew—than my parents’ house on Long Island.

But: Too much art, good or bad—yes, it’s a problem. What to do with it all?

The question is both fascinating and devastating, a palette knife plunging into the frightened hearts of most artists, meaning me. After nearly four decades of producing thousands upon thousands of works on paper, canvas, wood, and hundreds of objects, the notion of “too much art” cuts open a massive fissure in my life project. It’s not a new question, however. For years, I’ve felt the outflow of the complex eddies of my art-life reality: failure, hope, subsistence, survival, joy, value, fear, loss, and the specter (the truth) of its pointlessness. And that’s not even touching on the art itself. Is it too yellow? Too dumb? Too effete? Too obvious? No… The question is really, and mostly, about doubt. The bottomless fountain of it. I’ve secretly doubted the enterprise of art itself for years, and most frighteningly of all, the enterprise of my own art. It’s terrifying. I’ve been drowning in doubt for at least 20 years. It drives me mad; sometimes I can’t breathe. I despair. I attempt to rationalize it; doubt, like pain, is life, is consciousness. Isn’t it?

Meanwhile, I’ve accumulated artifacts. A history. A library. Many libraries’ worth. A museum of my own stuff as pathetic as it is. It’s not becoming, I think. It’s an anchor around my neck. Or too much cologne, and I don’t have enough lifetimes to shower it off.

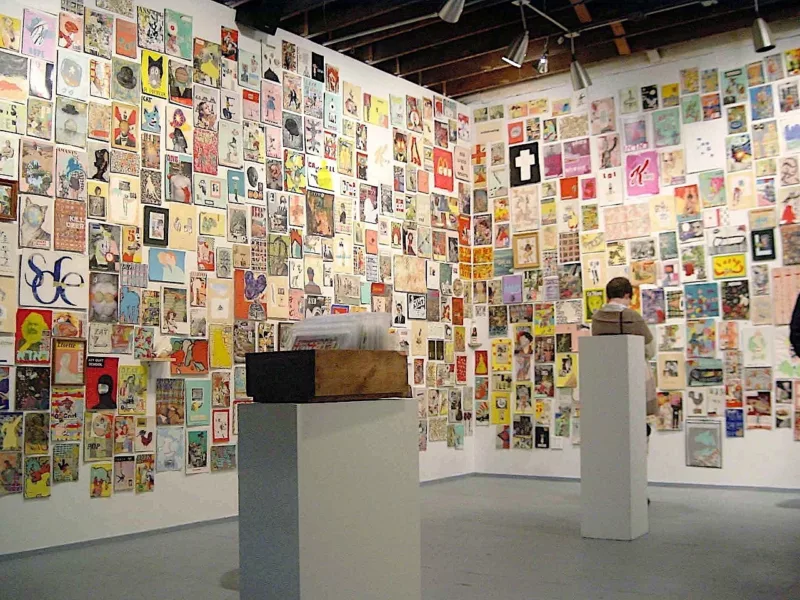

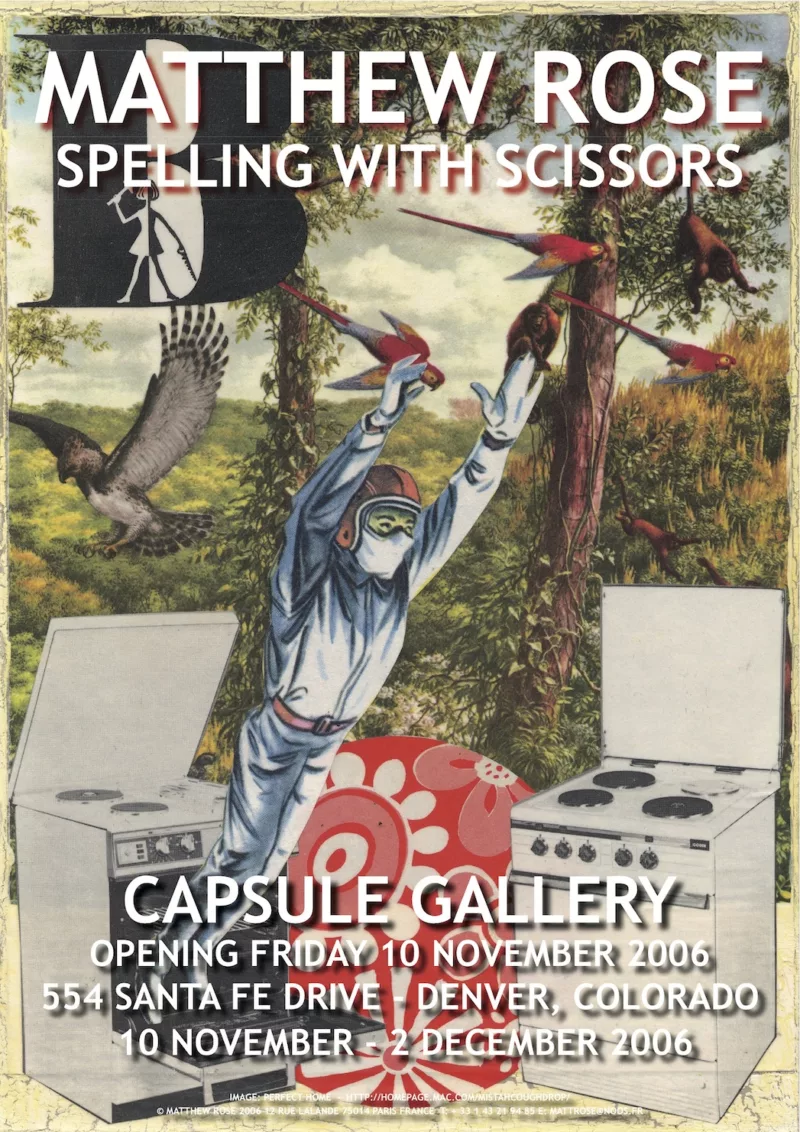

I have tried over the decades to “store” my works in massive installations. Five separate exhibitions over the course of years went up, each with a different name (Spelling with Scissors; Confessions; The End of the World, etc.), each show pulling together 1000 or more works all exhibited simultaneously: Sometimes spread out across several walls in a papering of the gallery space; other times in crates, offered up like used records (they were, in fact). Yes, some sold, helping me reduce the pile, checking the expanding tumor, and chipping away at my mountain of art. Sure, I exchanged the paper I toiled over for green paper; I earned a bit but never attracted the kinds of helpers (re: dealers) who could do what all artists want: move this stuff out of my house into someone else’s house.

Oh yes, it’s nice when everyone thinks you’re a genius and oohs and aahs at your “achievement” and shouts how “interesting” you are. A “real” artist! But again, I still return home, the prodigal son with the 1000-pound prizes and wonder what crime I committed in life that I would consciously harness my body and soul to an ever-accumulating mound of “achievement.”

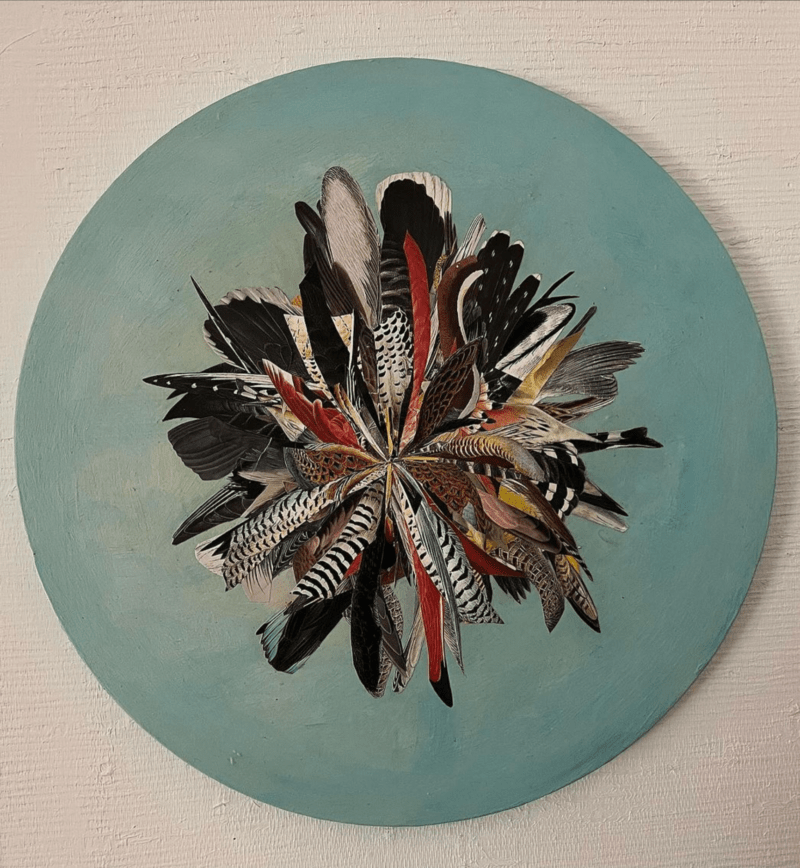

My obsessive construction of not just the surfaces plied upon canvases (or paper or torn book covers) but the real project: the manufacturing of my “self.” My fiction. My pollution, one might say. Who I was meant to be and who I am: My vanitas. My myth. All that crap I read in high school and college. Really, who am I (was I) kidding? Who cares for this folly? I’m no Rembrandt. Not even a drunk Jackson Pollock. I’m not even that digital fraud Wade Guyton. An artist whose scraps and garbage are sought after on ephemera web sites. Instagram is not my friend here. It’s exhausting, this paper chase. I collapse nightly in a sea of hundreds of picture books, torn papers, balled-up drawings, broken pencils, spilled paint cans, scissors, and X-actos strewn across the floor. My studio is a crime scene. I should be in a hospital, safe from my own refuse and my own “successes.”

[AS IS, Ricardo Bloch’s portrait of Matthew Rose’s Paris studio]

I am reminded of a verse from John Hartford’s anthem to the examined/unexamined life, “Tall Buildings”: “Now when I retire/And my life is my own/I made all the payments/It’s time to go home/And wonder what happened/Betwixt and between?/When I went to work in tall buildings.”

But it’s here (and there, and there, too). My stuff. Piled up, in boxes, in cartons, on tables, stacked along the hallway, on shelves. Everywhere. I sleep in a warehouse of it and close my eyes at night, asking, What’s the purpose of all this stuff? To help or to heal? Who? Me? Someone else? Or to generate income so I can pay my rent? Or “likes” and “hearts” from the black hole of the internet in order to feel some undoubtedly fake feeling about my endeavors? More likely some pathetic illustration of my own ouroboros (the self-consuming tail-eating snake). Live to eat, or eat to live? Drink to live, or live to drink? Or hoard material and finish “follies” in order to… hoard more of it? I can only think and worry about ending up like the Outsider Henry Darger, or the terribly celebrated Francis Bacon (ever see his studio, 7 Reece Mews, now ensconced in the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin?). A friend of mine, collage artist Robert Warner, passed away recently. Photos of Robert, who exhibited successfully for years at Pavel Zoubok in New York City, were shown to me privately a month ago. They show him floating as if on Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, but on a mattress surrounded by the detritus of a lifetime of living and working in his small, beaten-up studio on the Bowery in New York. Robert’s like a defeated castaway floating out to artworld heaven; he became the collage he was always making.

The fantasy that art, for its own sake, is the enterprise of culture creation to save the planet, awaken consciousness (my own or others), plot a course to salvation (religious or aesthetic), or simply alleviate the inevitable and minable edifice of boredom and pain amid the purposelessness and aimlessness of life, is perhaps just that: A fantasy, to be famous for a day or a week, to make a statement. To plant a flag and stand for something in this swamp of a cesspool we are living in and through, that’s worthwhile, no? Really, kids: Who wants a souvenir of my “work”?

You must see that it’s not just about stuff and “storage,” it’s about what we (I mean, I) just spent my life doing. The question isn’t too much art; it’s really about too much time, time spent on a project, each work an hour, a day, or a month. And the strange attachment (a psychological fault, no doubt) to some objects (but not others!).

Recently, a friend who has done me the serious favor of storing a sliver of my production (the early years!) in his house offered some of my works to a relative of his. He justified this gift by saying, “You told me you wanted me to leave your works in the woods.” Yes, I did say that, but not categorically. I didn’t say, Hey, have you given away my work lately? No, I suggested 25 years ago that he leave a piece or two in the woods near his house. As an art work. Lost and found. Give it away to the ether, to the tentacles of the forest, and to the earth.

When I found out about this gifting, I was told the relative was in the house alone, rooting through my work, which I had recently rearranged. It had been many years since I proposed spiriting off my art to folks I didn’t know. My friend thought he was doing me a favor by offering up the work and only told me about it weeks later as my art was winding its way in a Winnebago to Wyoming. I was stunned and told him so. I also told him I felt “violated.” It was a strong word I never associated with my work. There was no connection with this person, and hasn’t been one since. He never contacted me, never asked who I was or what I was about (as far as I know), but was obviously happy to take my artwork.

True, I am aware of the albatross of all this artwork around my neck, but it’s mine, for better or worse. For all its complications, I don’t hate it enough at this late stage in the game to hand it off to strangers; otherwise, I could have thrown it all away or pitched it into the Good Will heap of aesthetic bargains. Yes, quite a complex cocktail was stirred up. I did feel “violated.” And while the works were returned, I knew my attachment to them and how others regarded my attachment to them was uncomfortable; my friend hasn’t spoken to me in a month and I feel terrible about that. Possessions, value, and friendship. Bits and pieces of myself floating around out there in the wild. Quite a concoction of emotion.

So yes, I give artwork away almost as fast as I can make it. I’m like a character out of Beckett with pockets full of stones, moving them from one to the other or hiding beneath the house, waiting it out. Years ago, I left work in Paris telephone booths (when they existed) or on the Métro. Sometimes, I raced to collect them before anyone took them. Other times, I forced myself to walk away. Success!

These days, I’m more of an adult and often give an additional work or two when a big work is actually purchased. More often, however, I just rework existing pieces and end up archiving works in hidden layers beneath new ones. Yes. It’s an activity rife with contradictions and tomfoolery. I joke knowing this fool’s errand, kidding myself that I’m leaving it to the historians, curators, and art restorers of the future.

The truth is, I most often stash these prizes in my studio—under the bed, in closets, in cupboards, sometimes in the hallway, sometimes behind doors. Waiting for me to close that door for the last time or fall asleep for the last time, too. Matthew Rose time capsules for when I can no longer worry about their destiny or get upset by their disappearance.

Nota bene: In spite of my honest and good intentions, there are about 1000 works of mine still circulating in the US, most of them in boxes, stored somewhere unseen, collecting dust and decaying cardboard half-lives, each work speeding its way to an atomic bust.

Matthew Rose is an artist and writer living and working in Paris, France. His most recent books are HOME FROM INDIA (2023/Lulu) and Larry Gagosian And Me (2023/Lulu). He is also the editor of Trouble, a sometimes quarterly art review.

Instagram: Matthew Rose linktree @maybemistahcoughdrop

[Ed. Note: Matthew Rose wrote for Artblog starting in 2009. You can sample more of his lively commentary here.