Barbara Bullock: Fearless Vision at the Woodmere Art Museum through January 21 is a stunning and seductive exhibition, beautifully laid out on both floors of the circular-walled main gallery of the museum. Bullock has been an important figure among Philadelphia artists and crucial to the development of the African American cultural community here over the past fifty years. While the exhibition does not attempt to review her career systematically, it presents a clear view of her ongoing themes and expanding technical invention. Viewers will certainly be swept up by her visual intensity and exuberance.

Barbara Bullock (Woodmere Art Museum: Partial gift of the artist and museum purchase with funds generously provided by Robert Kohler, Osagie Imasogie, and Jim Nixon, 2020)

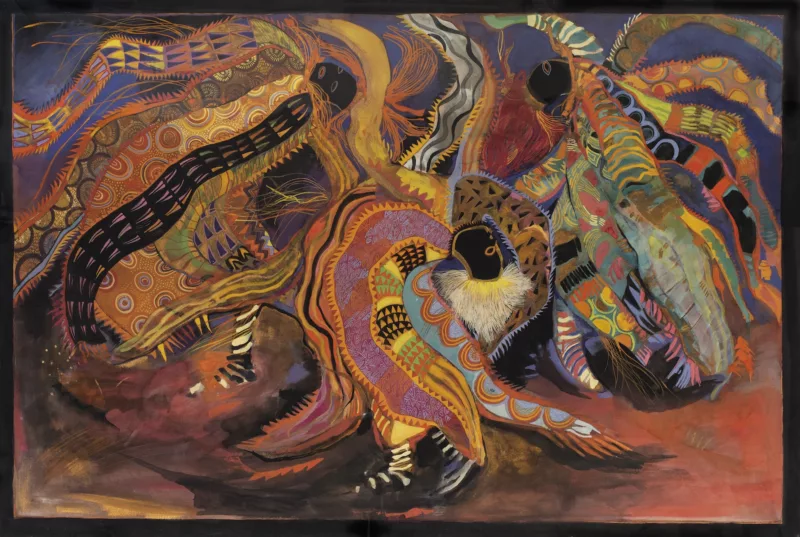

The artist has explored the experiences, spirituality, and embodied presence of African Americans, including individual and collective histories and cultural heritage. All of her work reflects her many travels in Africa and Mexico and her extensive study of the artistic and cultural practices she observed. Bullock has explored art as a means of reconstructing individual memory and telling communal stories, of building self-worth and healing pain, and connecting the living with the spirits of their ancestors. Her work is filled with energy and motion, and her long association with dancers is reflected in paintings that swirl, shimmy, stomp, and always imply musical accompaniment. They often invoke our other senses, conjuring the smells of perfumes and bodies and the tastes of food and salty tears.

The exhibition opens with three large, stunning paintings from 1985 that employ conventional formats which Bullock later abandons. “Remembrance” (74 x 40 in) is acrylic on canvas; it centers on a towering image of an African goddess surrounded by smaller figures in motion that represent aspects of spiritual imagery and practice. The painting is enlivened by rhythmic patterns of cowrie-shell ornamentation, extravagant headdresses, patterns of body paint and snakeskin. “Spirit Rain” (60 x 40 in), whose monumental, nude dancer fixes you with her intense gaze, and “The Whirling Dance” (49 x 68.5 in), which draws viewers into the vortex of its absolutely-convincing motion, are both painted in gouache on heavy watercolor paper. All three demonstrate visual devices that Bullock uses throughout her career: dramatic changes in scale, layering of forms, a broad range of intense color, use of repeat patterning at small scale to enliven the figures and to create an atmosphere of life and motion, and real or depicted effects of reflective surfaces and mirrors.

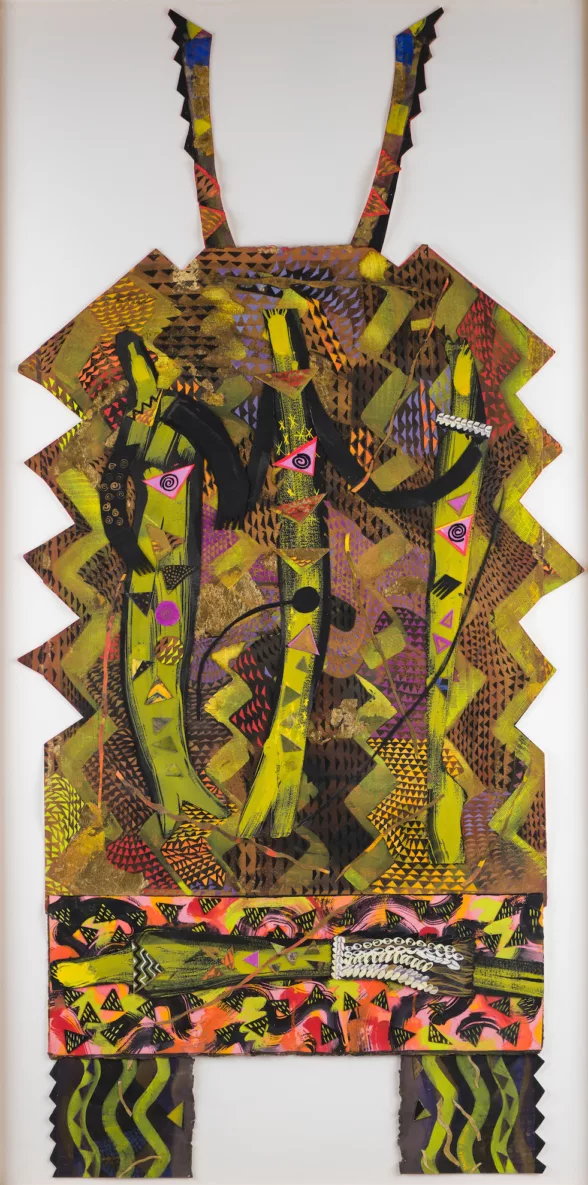

“Healing Altar” (1994, gouache on paper, 72 x 36 in) and “Healing Feeling” (1998, acrylic paint, matte medium and gold leaf on paper, 50 x 41 in) show Bullock’s next step in her expansive technique. Instead of using paint to depict forms, she used it to create intensely-colored, densely-patterned papers which she then cut and collaged to form her imagery. Cut-paper forms as a means of painting was a technique that Matisse used in his final decade, when his health prevented him from painting, but the effect of cut and collaged forms was anticipated by Matisse’s murals for Dr. Barnes, and Bullock credits the influence of the Barnes murals. With the collaged technique, she abandoned the previous, rectilinear format; the silhouette of this body of work is no longer that of the support but that of the subject, which sits directly on the wall, as a figure grounded in life.

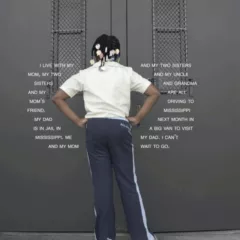

In 2007 Bullock made an actual altar (“Altar” mixed media, 80 x 68 x 39.5 in). It is a functional fixture in her home, influenced by those she saw in Mexico, and the only truly-sculptural work in the exhibition, although it has echos in a number of smaller pieces on view that grew out of her teaching: African-inspired dolls, pop-up books, memory boxes, time capsules, game boards, fans and masks. Some of the teaching projects are accompanied by the artist’s explanatory instructions, and are clearly intended to be used by others. The exhibition makes the convincing case that Bullock’s decades of teaching in public schools, community centers, and workshops for art teachers were more than day jobs performed to put food on the table, but were inseparable from Bullock’s own art. Her teaching and artwork fed each other. This unification also demonstrates her extensive research and preparation as well as her sensitivity, ingenuity, and generosity as a teacher and as a mentor to the art community.

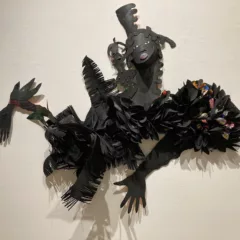

In 2007 Bullock took an enormous, imaginative leap with her technique. She began to use cut and painted paper in three dimensions to make what I still consider to be paintings, since they hang flat against the wall and derive from a painter’s concerns and primarily-illusionistic sense of space. They are most accurately termed “cut-paper reliefs.” She continued to collage patterned paper forms but then extended the imagery into space with multiple pieces of paper, usually painted intense black, that she cut, bent, curled, folded, serrated and otherwise fashioned to complete the images. They animate the paintings, so that viewers walking in front of them see changing colors and forms as they view them at different angles and interact with the shadows they cast. The reliefs intensify the sense of motion seen in much of Bullock’s earlier work.

The paper reliefs address subjects that challenge conventional representation: trauma, intense emotions, spirits and mythical creatures, and Bullock’s imagery merges into abstraction. She developed a unique language of expressive, one might say expressionist use of manipulated paper, which seems at times to explode from the central, colored core of the works. They began with the series, “Katrina,” in response to the disastrous effect of the hurricane on a neglected community. “Trayvon Martin; Most Precious Blood” (2013-14, 62 x 41 x 14 in), “Straight Water Blues” (2014-22, 35 X 21 X 7 in), “Bitches Brew” (2014, 48 x 72 in), all in acrylic paint and matte medium on paper, tell stories from newspaper headlines, contemporary literature, music, and African folklore.

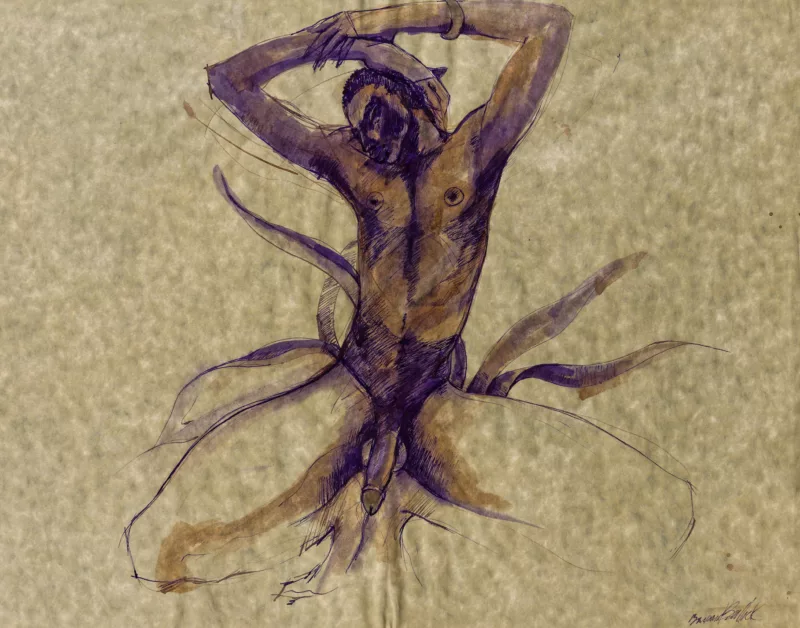

The second-story mezzanine gallery is hung with framed drawings and watercolors, previously unseen, and smaller versions of the collaged-paper works downstairs. They include “Jasmine Gardens,” an erotic series from 1982, which was not well-received by many of her colleagues because it represented men loving other men. Another series are portrait heads, friends of the artist and people only known from the news, recently-lost to disease and violence. Bullock never created subject boundaries; her subject is life, in all its manifestations.

Barbara Bullock: Fearless Vision, at Woodmere Art Museum to Jan. 21, 2024. Programs related to the exhibit on Jan. 13 and 20. More information and to register here.

[For more Artblog coverage of Barbara Bullock’s work, we suggest the late A.M. Weaver’s piece on the artist’s 2014 exhibit at LaSalle University Museum.]