TEMPORARY MONUMENTS

Art, Land, and America’s Racial Enterprise

By Rebecca Zorach

University of Chicago Press

$30.00, paperbound

When I decided to read and write a review about this book, it was based on my on-going internal aesthetic debate about preserving my own artwork and questioning the permanence of all art work.

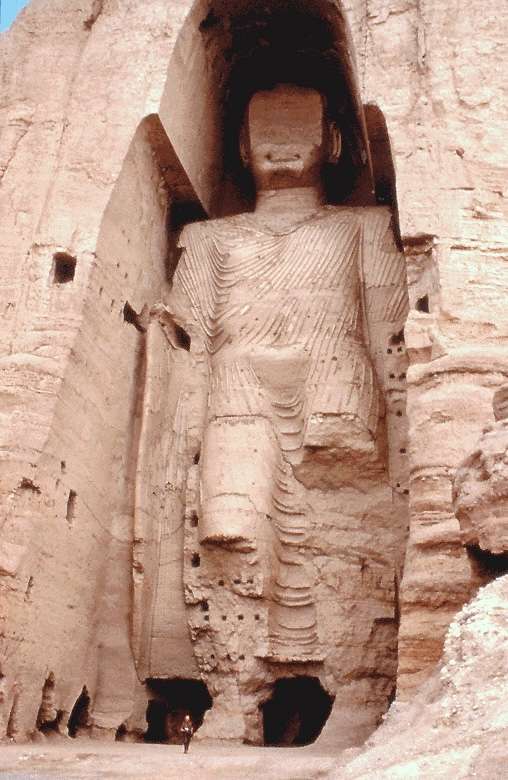

I continue to be saddened whenever I think about the Buddhas being blown up by the Taliban in 2001.

In her book, Temporary Monuments Rebecca Zorach writes about the power that monuments and their placement in the environment have in shaping the way a population perceives itself and the “others” in society. She writes about how those in power, those building the monuments, exploit, control and destroy. About the “others” living in a world of manipulation and victimization overshadowed by these exploitative monuments being touted as “art,” that is, beneficent.

Zorach details, in depth, the political use of monuments – statues, gardens, parks – to inculcate social boundaries, to enslave and to destroy.

It was a difficult and disturbing read, and I found her tone to be very condescending and judgmental.

She writes a lot about a system of judgments based on a White,*** European, Male HIS-story, that led to the nasty place the world is in today. Yet she uses these tenets to further her arguments.

I found myself asking – ‘Can we judge the actions of the past by today’s standards?’ Twice, Zorach poses the question or dilemma of historical context (on page 48 and again on page 133), twice not answered. Can it be answered!? Should it be answered!? Or, rather used as a reference to gauge just how far society has progressed and how much more work still needs to be done.

Zorach writes about the artist-activist being on the forefront of social reform. Again her tone is negative. On Earthworks – “Spiral Jetty”(Robert Smithson, 1970) is deemed overly aesthetic and a work of cultural appropriation, instead of acknowledging his concern for ecology and the reclamation of land damaged by an oil drilling operation. Smithson’s piece is contrasted with a project by Amanda Williams “Color(ed) Theory Suite” 2014-16, that addresses home, neighborhood and placeholding.

While I enjoyed learning about Amanda Williams’s art work, smashing “Spiral Jetty” felt like the Taliban smashing the Buddhas.

I guess I’m just tired of all the name-calling, bullying and hate, and this book adds to that genre.

I found Zorach’s discussion of “place” to be interesting.

She talks about the wilderness, the ungoverned, and the untamed;

she quotes from Thoreau (chapter 2). Chapters 5 and 6 contain a long discussion defining home and place.

Chapter 5: Home – color, abstraction, estrangement and the grid

Chapter 6: Walls and Borders – holding place

Space – the painter’s picture plane – is considered a workspace or place, a piece of land rather than a view of the world.

Place is a specific physical location, a position on a map or grid.

Grids as maps designate the placement of neighborhoods, public spaces and monuments, and by extension who can enter or be excluded by the boundaries on these grids – redlining, gerrymandering, racial politics, community dynamics, activism.

How was “the wild” – Indigenous America – transformed into “the grid”, THE monument of the 21st Century?

Henry David Thoreau – “…and it (a nation) is compelled to make manure of the bones of its fathers.” (page 59)

Zorach also quotes from Rosalind Krauss – the grid is “what art looks like when it turns its back on nature.”

Thoreau, abstraction and earthworks are woven into a story of how monuments in the form of sculptures, parks and paintings developed into depictions of factual information about Western Civilization. Then, idealization, iconoclasm, and natural deterioration revise the meaning. Whether it is blowing up World Heritage Sites (the Buddhas), tearing down Confederate icons (Robert E. Lee), the sinking and reemergence of “Spiral Jetty,” or repurposing abstraction, what art and archaeology teach us is that each civilization is built on the backs of and by the bricks of the previous civilization.

Change is the only constant.

***Zorach, on page 7 – “I’ve made a decision in this book to capitalize the word “white” when using it as a racial identity.”