Post by Andrea Kirsh

[This is part 1 of a two-part post.]

Philadelphia past and present

Mark di Suvero, Iroquois, recently installed on the Parkway in Philadelphia, photo by libby

I’ve had lots of occasion to think about public art (however you want to define it) since moving to Philadelphia in 2003. Full disclosure demands that I acknowledge my own history in the field: from 1988-1990 I was Assistant Director of Miami Dade County Art in Public Places (at the time one of the country’s oldest percent for art programs), where my responsibilities included administration, designing a care and maintenance plan and working with the county to see that the program was actually paid its 1.5% allocation. As everyone notes, Philadelphia has the oldest public art program in the country: the Fairmount Park Art Association, a private, nonprofit organization which dates to 1872, and the Mural Arts Program is happy to tell you that Philadelphia has more murals than any city in the world (currently more than 2,700, according to their website.

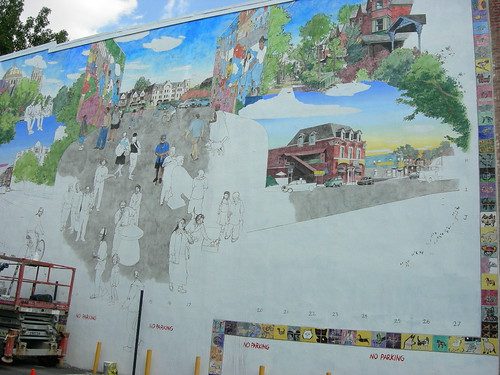

Mural Arts began as an anti-graffiti initiative and has continued to run educational programs for inner city youth. As a social program, it’s greatly to be commended. But as art? Mural Arts doesn’t even respect the artistic and visual integrity of the murals: a pair of murals is going up in my neighborhood and I attended the community discussions that lead up to them. After the artist’s design was finalized, and without consulting him or the neighborhood group, Mural Arts surrounded his walls with tiles painted by local students. It’s beginning to make me long for a blank wall or two.

I wouldn’t invite a single colleague to come to Philadelphia specifically to see the permanent artwork I know that’s been sited in public spaces during the past two or three decades. Permanent, of course, doesn’t apply to a few temporary projects, notably Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s installation at Eastern State Penitentiary or Mark Dion’s Urban Field Station at the American Philosophical Society–both installations now a thing of the past; nor does it apply to the Mummers’ Day Parade if you want to consider it as a performance piece. Claes Oldenburg’s “Clothespin” is great and much more integrated into the city fabric and consciousness than his “Batcolumn” in Chicago; but “Clothespin” dates to 1976. I admire Noguchi immensely, but his “Bolt of Lightening…a Tribute to Benjamin Franklin” is not a success.

And what’s happened since?

Looking North

Everybody, By Tibor Kalman and Scott Stowell, Part of the 42nd Street Art Project, 1993, Photo by Maggie Hopp

By comparison I think about my experience with recent public work in New York City. Every time I ride the subway to a new location I’m delighted to discover another artwork. The subway pieces may not push the envelope of contemporary art practice, but the range of artists commissioned since 1985 is varied and exciting, as are their responses to the sites; they contribute immeasurably to the experience of underground travel. The art ranges broadly in style and subject matter and the rigorous choice of materials, mostly easily cleaned glass or mosaic tiles, insures that they’ll remain looking good for a long time. MTA’s artwork strikes a difficult balance: it has ready appeal without pandering to the lowest common denominator of public taste.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles mirrored trash truck (at Art in the Armory art fair 2007) created for her Transfer Station Trans Formation, Sept. – Oct. 1984, 59th Street NYC Department of Sanitation Transfer Station. photo by libby

At the other end of New York public art are Creative Time’s various temporary projects which have most definitively pushed the envelope of public practice. Creative Time is a private non-profit, without the constraints of a public agency, although it collaborates with many city departments and with other arts organizations. I’m fortunate to have seen one of their earliest projects: Red Grooms’ “Ruckus Manhattan” (1975), the artist’s humorous and unconstrained interpretation of the city on Lilliputian scale, installed in the lobby of an empty downtown office building. Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ “Touch Sanitation” (Part One, 1984) is one of the definitive, if underappreciated, early feminist projects. “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference do” (1989) AIDS awareness posters mounted on city buses and Peggy Diggs’ Domestic Violence Milk Carton Project (1992) were significant models of socially-engaged work. My favorite memories of 42nd St. are the installations Creative Time sponsored (1993-94) in abandoned storefronts and on the marquees of former porn theaters, prior to the street’s redevelopment and Disney-ification.

GRAN FURY, Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do, 1989, Photo by Aldo Hernandez

I know Philadelphia isn’t New York. Not as large. Fewer artists. Not the art capital. But that’s not an excuse, and doesn’t explain the difference. Philadelphia has lots of artistic capital, and besides, all the art in New York wasn’t created by New York artists; some were imported. The success of those two New York programs (and that of several others I’m not discussing here, such as New York City’s Percent for Art program, Public Art for Public Schools, the Public Art Fund and Minetta Brook ) is due to the vision of their managers (staff and boards) who commissioned and fought for serious art, smoothed its way, and made certain the resources were there to produce it.

Ruckus Manhattan, by Red Grooms, Mimi Cross and The Ruckus Construction Company, December 16, 1981, Burlington House Lobby, Photo © 1981 Robert E. Mates

New books document both these programs and are available for inspiration and study.

[Part 2 reviews the two books and returns to the subject of the state of public art in Philadelphia].

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.