Unless you’ve visited the Musée Marmottan, Paris, or are old enough and fortunate to have seen the exhibition drawn from its collections many decades ago at the Met, get yourself to Gagosian Gallery by June 26 to see Claude Monet Late work. That is, go if you love painting. For you’ll see that rare thing – an artist who attempts something different in his old age, like Verdi taking on comedy. And in doing so, Monet made himself a twentieth-century painter and a great one.

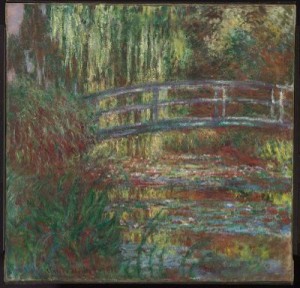

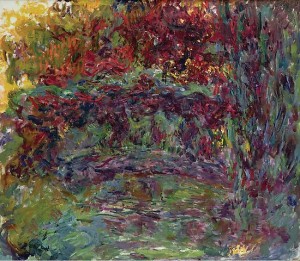

On a personal note, I spent serious time during college studying his painting of the Japanese bridge in his garden (below), of 1900, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. And I did see that exhibition of late paintings from the Marmottan at the Met; they made an unforgettable impression.

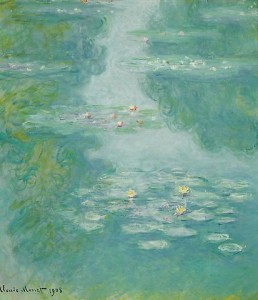

Monet’s last lifetime exhibition was in 1912. He was well aware of the new art currents of the Post-Impressionists and then the generation of Picasso, Matisse and others, and understood that Impressionism now belonged to the past. For his final fourteen years he refused to show work, although with the French victory in WWI he offered to donate paintings to the state. That offer turned into the twenty-two painting cycle that Clemenceau sited in the Orangerie, installed the year after the artist’s death. The Gagosian exhibition consists of eight water lily paintings from the first decade of the century, which Monet exhibited in 1909, and nineteen, nominally of various garden subjects, that remained in his studio until he died.

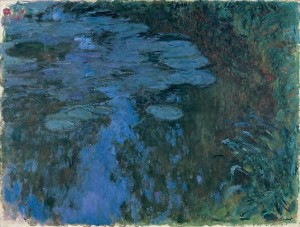

This later group is the eye-opener. With the earlier water lily paintings Monet was fascinated with the fact that the pond water is itself a flat plane which, at the same time, exposes what is below and reflects the sky above – a natural challenge, one might say, to the tension between figure and ground. In the later paintings the scale expands and all incident becomes one with the surrounding space. The brushwork takes on a life of its own, unconnected to the expression of forms

The paintings vary tremendously as to palette and also as to degree of finish; indeed I believe there’s serious discussion around the subject (ironic, perhaps, as the charge of unfinished was made against Impressionism from its beginning). They also vary as to presentation (some being shown without glass) and fortunately a few have survived unvarnished, so one can see both the variable sheen produced by working with some paints richer than others as well as the chalky mattness that the artist wanted for his later work (which sometimes disappeared before their initial sale, as his dealer, Durand-Ruel, didn’t think he could sell them in unvarnished state).

Monet’s late work anticipates so much painting from the 1940s to today that it’s almost impossible to wipe away our knowledge of the past ninety years and imagine how it appeared to fresh eyes in the 1920s. This exhibition is an extraordinary opportunity and not to be missed.

If you are intrigued enough by Impressionist technique to want to learn more , a wonderful book is available. Painting Light; the hidden techniques of the Impresssionists (2008, SKIRA, ISBN 8861306098) by Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George and Katja Lewerents was a collaboration among a curator, conservator and conservation scientist. Written as the catalog for an exhibition of seventy Impressionist paintings in the collection of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne, it is intended for a serious but general audience and is particularly readable. The fact that it addresses a single museum’s collection in no way limits its scope. The book will be just right for anyone who spends a lot of time in front of Impressionist canvases and is likely to be especially interesting to artists. While it doesn’t have the wealth of technical information or the theoretical framework of Anthea Callen’s 2000 book (which is now out of print), the bibliography will direct interested readers to further information.

The authors discuss the materials available through colormen, including the expanded palette that was the product of the nineteenth-century chemistry laboratory, as well as various color theories debated at the time A chapter looks at painting out of doors and the extent that it was common, the equipment involved, and various indications that works, indeed, were executed outdoors. Questions of spontaneity and finish are addressed as are changes to the paintings over time because of inherent vice (the term describing problems arising from the materials and their interactions and/or the way they were used), ageing of materials and deliberate intervention, as well as fakes.

The book is beautifully illustrated in full color with many enlarged details and a number of technical images. What I found most delightful were the wealth of period photographs which bring us so close to the subjects. There’s Nadar’s portrait of the color theorist, Chevreul, priming being applied to a canvas by a manufacturer, men using paint rolling mills, the interior of an art supply shop in 1900, Durand-Ruel in his gallery, a room in the Salon of 1857. Then pictures of the artists: Corot, Toulouse-Lautrec and Pissarro each at an out-doors easel, Cezanne with painting gear strapped to his back and Monet in his studio.

This book would make a wonderful gift, but you may not want to let it go.