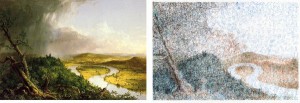

In lieu of brush strokes by the thousands, organisms by the thousands form the contours of the natural world in Mia Rosenthal’s American Landscapes, her first solo outing with Gallery Joe. In the show, which consists primarily of reinterpreted 19th-century paintings from the Hudson River School, Rosenthal converts the pastoral landscapes into images built on whimsical line drawings of units of individual species of flora and fauna.

Divided by phylum and kingdom into taxonomic constellations, the organisms are drawn alongside their colloquial names — southern flying squirrel, river otter, duckweed, red fox, southern bog, box turtle – and depicted in densely spaced combinations of one to four colors, which either remain isolated or melt together to form something else, be it a mountain, field, or river. The individual organism-units are precise, but Rosenthal is willing to let her drawings become a conglomeration of lines. At some points, all the information is obscured in the cross-hatching of lines crashing into each other and collapsing the spaces between them.

“Hudson Valley Landscape,” the first piece that greets visitors to the gallery, is a densely-packed mesh of plant and animal life. Row by row, the piece is divided into families of plants or animals, each section made up of a multitude of individual units representing the genera or species within that family. The result is electrifying, partly from the awe of perceiving the immense variety of natural creatures around us, or as a reminder of the terrifying breadth of damage that can be wrought on an ecosystem by human encroachment.

Rosenthal used internet databases to gather information about the organisms represented in these works, and viewing a drawing from the series provokes the daunting impression of staring at a digital information overload condensed onto a 20 x 30 inch piece of paper. The animating intent presents a simultaneous commitment to complete documentation and complete chaos.

Every specimen in these drawings is about the same size, and it seems like no two are ever repeated. The groupings of organisms by their biological traits gives an air of scientific rigor that playfully contrasts with the whimsical drawing of the animals and organisms. Invasive forms of plant-life are included, like the sensitive joint vetch, which reinforces the idea of the landscape as under attack. Rosenthal’s unique method also allows for play, like in “After Kensett: Shrewsbury River, New Jersey, 2012,” where a landscape’s three-dimensional depth is also Rosenthal’s two-dimensional diagram of fish and riverbed vegetation.

This solo show by Rosenthal, who has previously exhibited work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art (her alma mater) and Tiger Strikes Asteroid, is a welcome addition to the American landscape tradition. But it is also touching as an homage to artists like Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church, who were closely linked to the ideology of the transcendentalists, Thoreau and Emerson. In that same spirit, Rosenthal’s drawings present the idea of nature teeming with life as a tautology, with nature’s creatures literally forming the lines of the composition.

As Emerson wrote in The Natural History of Intellect, “What strength belongs to every plant and animal in nature. The tree or the brook has no duplicity, no pretentiousness, no show. It is, with all its might and main, what it is, and makes one and the same impression and effect at all times. All the thoughts of a turtle are turtles, and of a rabbit, rabbits.”

The collection of magnifying glasses at Gallery Joe are indispensable to viewing and enjoying Rosenthal’s drawings, but ironically, the glasses weren’t intended for this show – they are for Sharka Hyland’s exhibition in the adjacent gallery. The magnifying glasses were just so well-suited to examining the miniscule detail of Rosenthal’s works on paper that visitors gradually carried them over and left them around the room.

American Landscapes, Gallery Joe, 302 Arch St., through April 14, 2012. For more information, visit miaonpaper.com or GalleryJoe.com.

Ben Meyer is a writer living in Philadelphia.