Joe’s Junk Yard, Lisa Kereszi’s photo-chronicle of her family’s junkyard in the South Philly suburbs, begins with Lisa’s two essays, “Scrap with Joe” and “Down the Yard,” telling the history of the family business.

Kereszi’s grandfather Joe Kereszi founded Joe’s Junkyard in 1949. After his death in 1992, her grandmother Eloyse and her father Joe Jr. ran it until 2003, when they sold it to the sons of Joe’s brother Lou, who ran a more prosperous junkyard next door. The junkyard was a magnet for broken down cars and hard luck people, and its aura pulls me in. There’s a style about the place that only an insider could capture. Looking at the photographs, I feel how heavy things were both physically and emotionally, and how the weight created a center of gravity.

The Kereszi clan shared the wonderful habit of accumulating things. They seemed never to have cleaned up and started fresh; the disarray makes its own orderly chaos. For 50 years they shared the job, the seven-acre lot, the office, the garage bays. They shared the cars, the tools, and an arsonist burned the tires when there was no money to dispose of them properly. They shared the fines and bills and every last screw, nut and bolt through some good but mostly bad years. Because so many things are competing for space, the stuff almost seems more dramatic than the people.

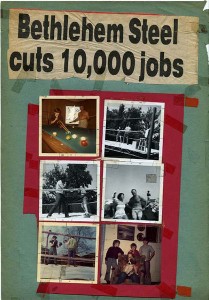

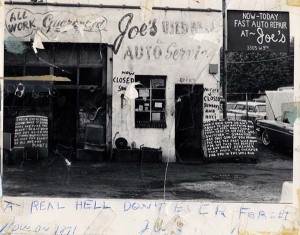

Lisa was influenced by two powerful patriarchs, Joe Sr., former boxer and midnight collagist, and Walker Evans, specifically Evans’s iconic 1935 photos of the steel stacks and cemeteries of Bethlehem, PA. In her book, Lisa reproduces pages from Joe Sr.’s personal, confessional scrapbooks. He started making scrapbooks in 1973 after his son Rocky was killed. He wrote self-deprecating, sad statements on snapshots raided from the family albums, Scotch-taping them together with disturbing newspaper clippings, official documents, and church oddments. Joe’s own sense of failure, his thwarted ambition, the death of sons Rocky and Mark, the destruction of his home in a fire and other demons have their say in his scrapbook. Joe was an outsider artist who wove the printed word and image in shocking ways. His disappointment reminds me of what Walker Evans said about finding photography only after failing as a writer: “I wanted so much to write, that I couldn’t write a word.” Evans achieved dramatic or comic effects by photographing the printed word, but Joe—much edgier–hand printed nasty signs on car hoods warning off “cheaters” who might want to exchange “switched” parts. Life may have knocked Joe Kereszi down, but he was not quiet about it.

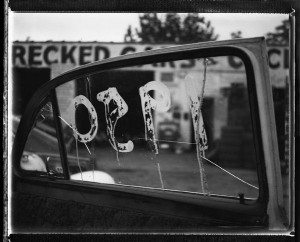

Relying on the printed word as well, Joe’s Junk Yard includes 45 photographs with words or signs and 21 without. Strategically cropped fragments like “Big Mac,” “Wrecked Cars and…,” “Out Wild Dogs,” “I Am Scared,” “Junk Yard Dog Ma…,” “Help,” “Guess,” and “Cadillac” speak as clearly as the bumper stickers: “My Other Car Is A Piece Of Shit Too!” and “I Need More Money And Power And Less Shit From You People.”

Kereszi uses color for punch. Her photos have a “deadpan or dumb quality,” to quote her. She knows “it’s the thing you aren’t supposed to do–plunk the thing down in the center of the frame.” A recent Smithsonian article on William Eggleston discusses banal composition and color in his iconic photograph “Tricycle and Memphis.” The article links Eggleston with Walker Evans, through his documentation of “homely” objects and tools, and with Stephen Shore, another master of color photography. (Lisa studied with Shore at Bard.) Eggleston’s tricycle dead center in the frame made art critic Hilton Kramer mad enough to call it “perfectly banal” and “perfectly boring” at the photographer’s 1976 New York MOMA show. Kereszi’s “dumb” compositions leave plenty of room around her subject: they are detached but not banal. She aims her camera straight at objects and scenes, just like people point fingers and stare in biker bars, livestock sales and trailer parks. Her vision is freed up by bad manners. Shooting from a safe distance, yet also risking insulting her subjects, Lisa’s a family member who doesn’t have to please. If you adopt her point of view as the insider/outsider, the junkyard is both a cultural desert and a gold mine: you can be like her, stuck there through the bitter end, as well as the one who made it out and came back with three diplomas and a camera.

Looking at Kereszi’s photos, I thought of Harmony Korine’s Gummo, Larry Clark’s Kids, and the Maysles Brothers’ Grey Gardens and Salesman, movies that showcase eccentrics. Like Toshiro Mifune to Akira Kurosawa, Lisa’s dad Joe Jr. is the star of Joe’s Junk Yard. He’s the guy who wears a leather belt with “Boss Hog” printed on it, who keeps baseball bats behind the office door. He sits splay-legged like a king on a pile of tires, he broods in his pink Cadillac, and he sits dead center in the office, nearly invisible amidst the clutter. Lisa’s by his side as he puts oil in the Cadillac, as he counts money in the truck cab, and as he prepares for swap meets. In one of the most emotional photographs in the book, we see him small, blurry and distant in the emptied-out office the last week it’s open. At the end of the book after the junkyard is sold, we see him heavy, stiff and bundled up and looking displaced outside his home in Media, PA. But he was a big man in many people’s minds. Lisa remembers, “We walked down the boardwalk [at the shore], two hours from Philly, and everyone would know him. Big Joe, big man on campus, so for there to be a book about him just makes sense.”

Joe’s Junk Yard is edited and designed by Michelle Dunn Marsh. The book includes a forward by photographer Larry Fink, Kereszi’s advisor at Bard College, and an essay by Ginger Strand, an eclectic New York City writer, traveler, and professor. Find updated details and events by clicking here.