One of the most talked about exhibitions of the year, the Museum of Modern Art’s Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925 has been equally acclaimed and disparaged. The show, curated by Leah Dickerman with Masha Chlenova, tackles a mammoth objective: to chart the advent of abstraction as an interdisciplinary phenomenon spurred forward by a vast network of creative individuals. A whirlwind exhibition of over 350 works by 84 artists, including composers, writers, filmmakers, painters and sculptors, it is an overwhelming spectacle that is difficult to take in all at once.

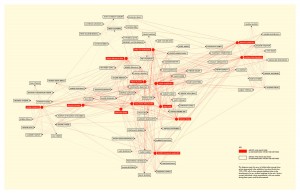

What is clear from the torrential response by art critics is that Inventing Abstraction takes on more than just an uncontroversial historical survey. Dickerman uses the exhibition to make an argument for a new way to view abstraction: not as a turn to ‘purist’ painting initiated by select genius, but as a cross-medium trend sustained by productive relationships. This is underscored by the show’s entrance diagram, which links pioneering intellectuals together in a web of interconnectivity— a social network before the advent of MySpace or Facebook. An interactive version of the chart is available here.

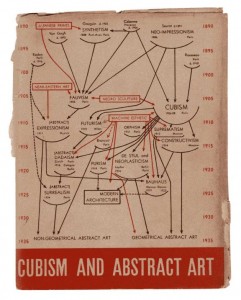

In addition to giving visible shape to fruitful social relations, the diagram assumes the role of connecting Inventing Abstraction to MoMA’s institutional history. It does this by deliberately evoking the aesthetic of Alfred H. Barr’s 1936 flowchart for the museum’s seminal Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition. However, unlike Barr’s creation, which presupposes a linear evolution of art movements (from Neo-Impressionism to Cubism, Constructivism, and then Geometric Abstract Art, in a seamless forward progression), Dickerman’s embraces the more complicated nature of an international exchange of ideas simultaneously driving towards increased abstraction.

In another nod to the museum’s history, Inventing Abstraction opens with a 1910 painting by MoMA darling, Pablo Picasso. Femme à la Mandoline bridges the connection between Cubism and abstraction, coming increasingly close to non-representational painting, but falling just short. Dickerman posits that abstraction was still not conceptually possible in 1910. Yet only two years later, in the “watershed” year of 1912, a myriad of artists showed abstract work in public exhibitions. Assembling a critical mass, they were Arthur Dove, Robert Delaunay, František Kupka, Francis Picabia and Fernand Leger, among numerous others. At the beginning of that year, Vasily Kandinsky exhibited Composition V and published his treatise on the spiritual in art. A new culture of interconnectivity, spurred by the arrival of trains, cars, print media and loan shows, allowed these concepts to disseminate swiftly.

The curator takes care to present a number of luminaries in a different light, while also highlighting lesser-known artists. A wall of Piet Mondrian works, for example, showcases the eminent artist’s move from scarcely recognizable forms to purely geometrical ones. A dramatic juxtaposition of Kazimir Malevich paintings with Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column similarly puts two well-known players into striking new perspective.

Other highlights include Morgan Russell’s spectacular 11-foot-high Synchromy in Orange (appropriately subtitled “A la Forme,” or “To Form”), Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, Fernand Leger’s Les Disques and Contrast of Forms series, and a number of chaotically colorful pieces by Kupka.

Dickerman makes sure to allocate wall space to women artists of the time, notably Vanessa Bell, Katarzyna Kobro, Sonia Delaunay-Terk and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (the latter two are often overshadowed by their husbands). Also included are a number of Hungarian, Swedish, Polish and Russian artists. Noticeably absent, however, are works by non-Europeans.

A number of multimedia experiences add depth to the exhibition, including a gallery playing a selection of atonal music by Igor Stravinsky and Edgard Varèse, as well as several conceptual films by László Moholy-Nagy and Hans Richter.

For all of these treasures, either newly re-contextualized or rarely before seen, Inventing Abstraction is well worth a visit. It is also interesting to note that there is another layer to the exhibition— comprised not of the arresting experience of viewing the work on display, but of the rhetoric surrounding the show.

Because MoMA is often characterized as the ‘old guard’ of modern art— an institution that from its inception ventured to classify and define preeminent art movements— reactions to its thematic shows are often mixed. Should one establishment, by virtue of its ability to produce blockbuster loan exhibitions, be given the power to identify the ‘inventors’ of abstraction? The use of the word ‘invent’ invites tension, as it points to the creative genius of seminal theorists at the expense of others. As a result, much work has been done to identify the key figures left out of Dickerman’s narrative. Paul Klee and Joan Miró, first and foremost, are cited as key omissions. Tyler Green of Art Info identifies Matisse as another oversight; a precursor to brightly-colored abstract art, Matisse’s work also flirted with non-figurative composition, as did Picasso’s.

In addition to important figures, G. Roger Denson points out that whole cultures have been skipped over in the show’s account. In his Huffington Post article, Denson mounts a searing assault on the exhibition, asserting that abstraction could be said “to have originated spontaneously as much in Africa as in Asia as in Australia as in America as in Europe.” The show’s partial narrative led Jerry Saltz to proclaim that its title should be “‘High Museum Abstraction: History Written by the Winners’ or ‘White Abstraction.’”

While the exhibition may offer only a selected view of abstraction, it nevertheless presents an amazing array of artwork from across Europe and North America. It challenges accepted understandings and has set off an enriching debate. Inventing Abstraction will live on in the novel thought that it has fostered, through both the catalogue and the art world’s critical response.

Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925, through April 15, 2013. Joan and Preston Robert Tisch Gallery (6th floor), Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, NYC. All images courtesy of MoMA Imaging and Visual Resources Department unless otherwise noted.