[Andrea visits David Novros’ recently restored site-specific work, and discusses the pros and cons of creating art destined for one space. — the Artblog editors]

In mid-June, I joined a small group to celebrate the recent restoration of David Novros’ untitled mural (1970) at Donald Judd’s Spring Street home and studio, which is under the auspices of the Judd Foundation. It was one of two works–the other a large, light work by Dan Flavin–that Judd commissioned for the five-story, cast-iron industrial building at 101 Spring St., which he purchased in 1968. Judd and Novros both felt strongly that the siting of artworks was crucial, and the opportunity to create a permanent work for a given situation and known lighting was ideal.

Perfect partnership

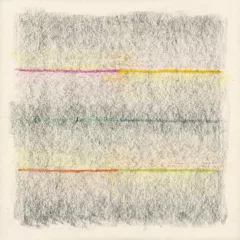

Novros is one of very few contemporary artists working in the traditional method of fresco, in which unbound pigments are painted on wet plaster, so they become bound with the structure of the supporting wall. Fresco produces particularly clear and slightly matte colors, and suits Novros, who is an extraordinarily sensitive colorist.

In the late-afternoon light from the huge windows adjacent to and opposite the mural, the colors were mesmerizing. Novros’ composition of abstract forms and intervals has both a sensuality and deeply personal quality that goes far beyond any associations one might have for hard-edged, geometric abstraction.

Novros’ prior site-specific work

I had met the artist in Miami, in1984, when he was working on a fresco commissioned by the General Services Administration (GSA) for the two-story loggia of the David W. Dyer Federal Building and United States Courthouse–a 1930s Mediterranean Revival structure. That mural, an extraordinary environment of saturated color and abstract forms, became the subject of a battle among some of the courthouse judges and staff, the GSA, local preservationists, and the greater art community. For years, it was damaged through inattention, hostility, and neglect.

The building was once one of the busiest and most dangerous of federal courthouses, housing the trials of Meyer Lansky, Manuel Noriega, and many drug kingpins. Since 2007, when the court moved to a modern building across the street, the historic structure has been unused. The GSA has issued a Request For Information (RFI) for suggested reuse, and Miami-Dade Community College has indicated that it would like to purchase the building.

The downside of site-specific artwork; 101 Spring St. restoration

At the Novros reception, copies of the catalog for the artist’s recent exhibition, held at both the Museum Wiesbaden and the Museum Kurhaus Kleve, were available for guests. One of the essays discusses the artist’s aversion to creating work that becomes a market commodity, and the fact that permanent installations address this, as well as satisfying his concerns about siting.

There is no question that the extremely sensitive placement of artwork, which Novros favors and Judd championed in his properties in New York and Marfa, provides the ideal viewing. But the museum catalog also highlighted the downside of this position, which is that the survey of Novros’ work contained none of what he considered his most important production over the past 44 years.

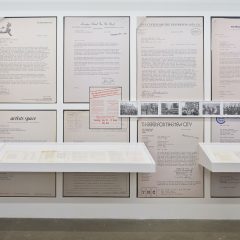

101 Spring St. is the only intact, single-use, cast-iron structure in Soho. Its conservation was intended to preserve the original structure and Judd’s interventions; to modify the atmospheric conditions in order to preserve the art collection; and to bring the building up to code, necessary for public visitation. It began with scaffolding, which covered the façade for a decade. 1300 pieces of cast iron were conserved; windows were repaired or replaced; interiors were modified, and all of the artworks were cleaned. The building is a part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (HAHS) program.

Guided visits for small groups at 101 Spring St. began in 2013. The building is a must-see for anyone interested in New York City industrial architecture; adaptive reuse of these buildings; artist’s work and living spaces; New York artists’ culture of the 1960s-70s; and Donald Judd’s oeuvre and collection, including one of the only modern frescos you are likely to see. 101 Spring St. is also surely one of the most beautiful interiors in New York–an oasis of calm, detailed control of light and space, and opportunity for contemplation about art, its siting, and its relationship to the world.