[Susan reports on her travels through several Irish museums, discovering the depth and variety of Irish contemporary art and the fascinating preservation of the country’s natural history. — the artblog editors]

Dear Philadelphia: great news! This spring it was my good luck to have an extended stay in Ireland–in beautiful and rustic Ballycastle, County Mayo–thanks to a generous fellowship from the Ballinglen Arts Foundation. I made a short visit to Dublin after one week and, later, when my residency was over, I decided to stay on in Ireland (eking out my limited studio wardrobe) to get to know the contemporary art scene in Dublin. Here are a few highlights.

Royal Hibernian Academy

I made my first visit to the Royal Hibernian Academy in April on the last day of The Untold Want, a show of diverse work addressing aspects of the sublime: nature, mortality, and freedom. RHA director and curator Patrick T. Murphy was the director at ICA right here in Philly from 1990-98, and has continued to produce interesting, ambitious shows in Dublin. Murphy wrote that the goal of this exhibition was to explore these extremes of human experience with “a poetic and spacious sensibility…” and the show included photographs by Nan Goldin and films by Ana Mendieta. Lovely color field paintings by William McKeown were juxtaposed with Dorothy Cross’s bronze sculpture of a digitalis plant with human fingers and a 1985 film by Vivienne Dick showing the harvesting of peat from a bog.

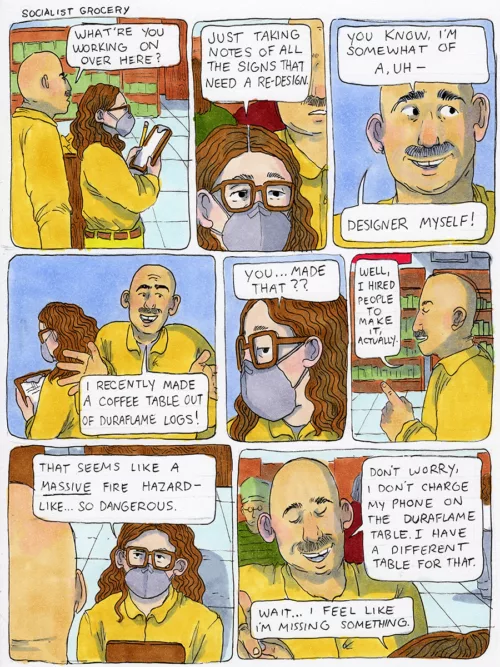

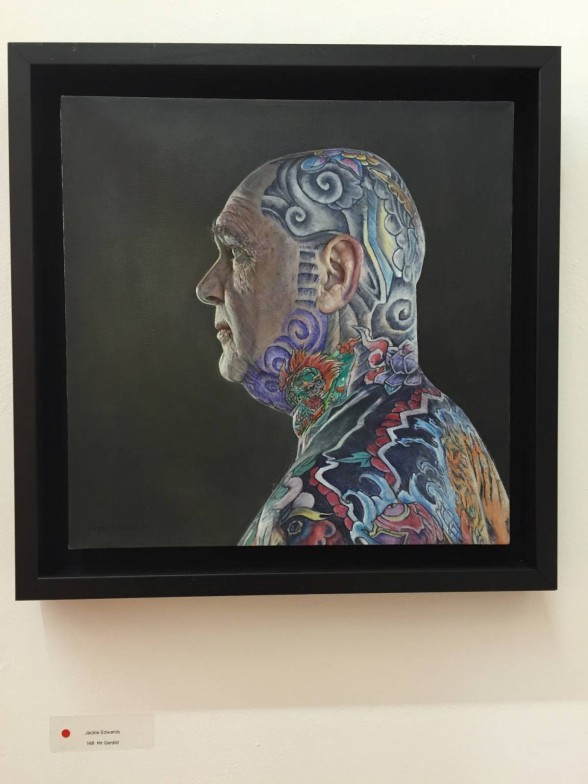

On my second visit, I got to see the RHA’s huge and amorphous annual exhibition, which presents a populist cross-section of recent artistic activity by Irish artists, from the most esteemed masters to students and hobbyists. With a little fortitude, the show rewards the viewer, and I particularly enjoyed seeing the sculptures of John Behan, smaller works by Holly Somervile and Jackie Edwards, and the compact expressive paintings of Donald Teskey, where land and weather are woven together with layers of understated emotion.

Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA)

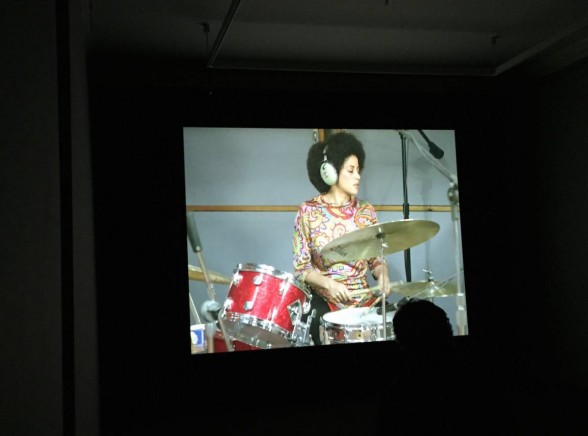

I was able to attend the opening of Mise en Scene, a massive exhibition of recent photographs and a major new film by the Canadian artist Stan Douglas. This impressive show is an unexpected pleasure; the huge, exquisitely detailed photographs of socially relevant reenactments are riveting, and I could have stayed in the dark room showing Douglas’ six-hour film loop “Luanda-Kinshasa” all night. This pseudo-documentary film shows a recording session, an extrapolated fiction based on Miles Davis’ sessions at the Columbia 30th Street Studio in the 1970s, and the camera weaves around the various performers, all of whom are real-life musicians passionately collaborating and improvising.

I poked around the rest of the museum as well, and found some beautiful hanging sculptures made of plastic sheets and other debris by Karla Black, a 2011 Turner Prize nominee who lives and works in Scotland. With work boots on and underdressed as usual, a few days later I visited IMMA for a second time for the Summer Rising IMMA Festival, a chic, artsy gathering with techno music, fancy cocktails, and an inspired slate of performances and readings. One of the best was an incisive and hilarious performance by Ella de Burca, which involved her interactions from the conductor’s podium with the characters of Rilke, Beuys, Mann, and Wagner (all without pants). I also thoroughly enjoyed a tensely introspective reading by Claire-Louise Bennett–I tracked down her excellent book Pond the next day and read it on the flight home.

National Museum of Ireland–Archeology

This museum is remarkable in the depth and richness of the objects it contains, which date from very early stone implements to hoards of delicate Bronze Age gold jewelry to Celtic, Viking, and medieval artifacts. I also had a firsthand introduction to bog bodies: the leathery, well-preserved remains of victims of sacrificial rites (from around 400-200 B.C.) associated with sovereignty, kingship, and boundary issues. Many of these bog bodies have only been discovered recently and have fired the imaginations of current artists and composers. One turned up as a theme in a musical performance I attended by the Concorde Contemporary Music Ensemble at the RHA (“Bog Bodies,” 2015, by Eoin Mulvaney) and another is the inspiration for “Four Fold,” a strangely personal installation about bog-body autopsies by Sam Keogh at the Douglas Hyde Gallery at Trinity College.

National Gallery of Ireland

The National Gallery is currently undergoing renovations but parts of the museum are still open. Beside the masterpieces from the permanent collection (Lippi! Titian! Vermeer! Caravaggio!), there is a small exhibition surveying two decades of work by the well-known Irish painter Sean Scully. Scully’s paintings surprised me with their solid and sculptural personae that gave me the strong impression of “well-balanced,” even “happy” people–this latter impression may have come from the many hints of brightness under their dark, neutral exterior surfaces. I enjoyed seeing two recent series of photographs by Scully shown along with the earth-colored, striped paintings he is known for. One series, Manhattan Shut, shows close-ups of closed security gates in New York; the other, Aran, documents expressively patterned dry-masonry stone walls. (Photography is not permitted in the NGA Scully exhibition, but I managed to get a few pics at the Hugh Lane Gallery.)

Other favorites

I could have spent all day (and I did) at The National Museum of Ireland–Natural History, aka the “Dead Zoo,” a wonderful, historic cabinet-style museum with an enormous collection of zoological specimens. Equally engrossing is the Chester Beatty Library, which contains rare and precious manuscripts, books, and prints, including beautiful, geometric illuminated Qur’ans, Mughal albums of miniatures, and thousands of Japanese Edo prints. The Dublin Writers Museum is an eye-opening–if somewhat low-key–experience. However, it was truly exciting to meet Robert Nicholson, the narrator (and star) of the film “James Joyce’s Dublin: The Ulysses Tour,” which recounts the chapters of Ulysses through a trip around modern Dublin, and to get his suggested reading list of contemporary Irish literature.

Francis Bacon’s studio at Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane is a marvel in the epic proportions of its chaos: it is an accurate and claustrophobic replica containing over 7,000 objects (among them 100 slashed canvases) which were catalogued and relocated exactly as they had been in Bacon’s studio in the South Kensington neighborhood of London. Bacon was born in Ireland, but lived in London for most of his life. This museum also contains a large number of Impressionist paintings, a Sean Scully room, and some small gems of Irish painting, including Sarah Cecelia Harrison’s “Portrait of the Artist”.

And in a side trip to the National Museum of Ireland–Country Life in Castlebar, I enjoyed seeing wonderful traditional baskets, textiles, and boats, as well as On Sight 2015: Welcome to the Stranger: Migrant People, Places, and Spaces, a selection of site-specific pieces on the grounds by Irish artists. Nuala Clarke’s lovely and evocative piece, “The Mariner’s Laundry,” is made from ephemeral garments and scraps of cloth washed up on the beaches of Mayo County. It is sited on the shore of the lake and brought to life by the wind.

Project Arts Centre

I was lucky enough to get a sneak peek into the installation of The Riddle of the Burial Grounds at the Project Arts Centre, which was not scheduled to open until the day after my return to Philly. This ambitious exhibition includes the work of 16 artists and fills the whole Centre, even the spaces normally reserved for performances. The theme of The Riddle of the Burial Grounds, curated by Tessa Giblin, is the ultra long-term impact of human activities on the planet, as well as how the signs and ruins of our time will be interpreted far, far in the future. Giblin refers to the challenge of designing a marking system for a New Mexico nuclear-waste containment site that would be understood hundreds of thousands of years in the future, in the context of the unknowable meaning of standing stones and megalithic monuments that have stood in the Irish landscape, by comparison for a mere five to seven thousand years.

“Containment” by Peter Galison and Robb Moss, a documentary film-in-progress about nuclear waste, will be shown, as well as “Mineral Rights, Ireland,” Lara Almarceui’s ongoing project to obtain rights to Irish iron deposits as an individual, a strangely complicated process she has attempted in many countries and has found success with so far only in Norway. Stéphane Béna Hanly’s underwater installation of unfired clay portraits of Thomas Midgely (inventor of CFCs), Alexandre Parkes (inventor of plastic), and Robert Oppenheimer (Manhattan Project) will–predictably–have unpredictable results. The three clay heads are made from different kinds of clay and situated inside three glass tanks of water. According to Béna Hanly, each on their own schedule, the heads will bubble, erode, and slowly settle on the bottom of the tanks.

My whole time in Ireland was extremely productive and rewarding, but in the end it was especially fabulous to see that, coexisting with a rich heritage of art, music and literature, the art scene in Ireland today is compelling, vibrant and a whole lot of fun. I’ll be back!

Susan Hagen received a fellowship from the Ballinglen Arts Foundation, Ballycastle, Co. Mayo, Ireland, and spent many happy weeks working on her sculptures and drawings this April and May in the Foundation’s studios in Ballycastle. Susan is a Philadelphia sculptor who has exhibited her work in museums and galleries across the U.S., and has written hundreds of articles about art for the artblog, Philadelphia City Paper, Woodwork Magazine, Hand Papermaking, and many other publications. Her work is represented by the Schmidt Dean Gallery in Philadelphia. For more information: missioncreep.com and susanhagen.net.