One-time graffiti writer Roger Gastman’s new documentary “Wall Writers” is an emotional and opinionated immersion in the facts, fictions and legends of the street art phenomenon the movie calls “the largest art movement in the Twentieth Century.” Whether you consider graffiti to be vandalism (the movie doesn’t) or a heroic gesture by poor and unempowered youth to make a mark on the world (the movie does), you will find the well-paced, colorful interviews and archival footage compelling, and the earnest, now middle-aged-or-older writers and their stories highly sympathetic.

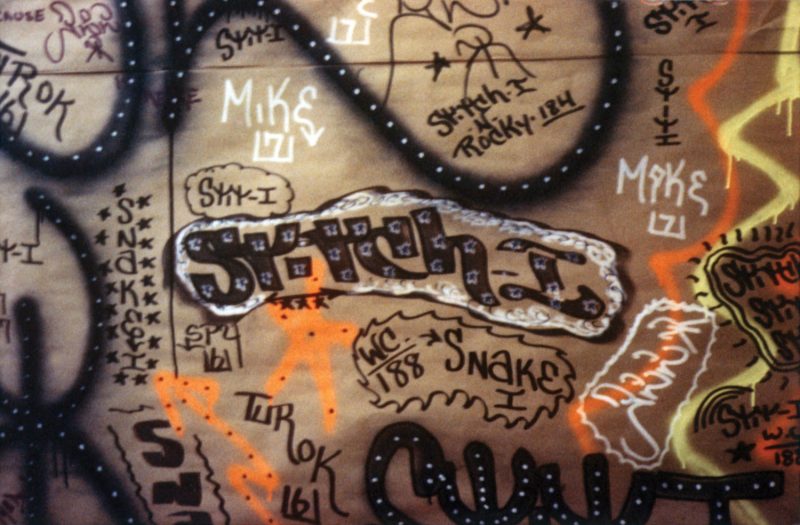

“Wall Writers,” whose 350-page companion book Gastman also produced, concentrates on the period between 1967-1972 when graffiti first came on the scene in urban centers like New York and Philadelphia, the two disputed birthplace(s) of graffiti. In 79 minutes, the film creates a story that is honest and makes the early writers — Taki 183, Rocky 184, Snake 1, Chewy Kid, Cool Earl, Cornbread, Cool Klepto Kid, Mike 171 and more – seem like innocents rather than vandals and criminals.

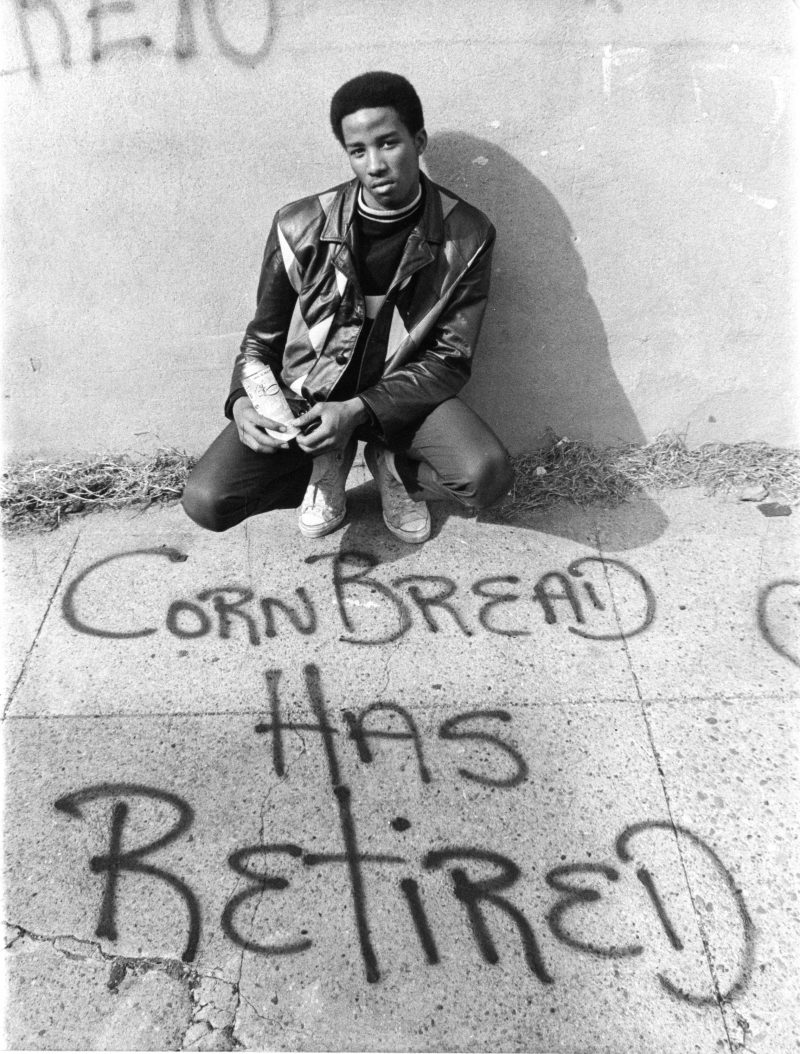

CAPTION: Portrait of ROCKY 184. Photo by Pete Duvall

Motives

“I did it because I could,” says Rocky 184, the one woman graffiti writer who gets a deep look in the movie. The self-proclaimed tomboy from Washington Heights is not alone in her unfocused motivation. “I was bored,” says Snake 1. It was not political, say a number of the others. The best, nuanced comment is from Cool Earl, who says “It was a sign of the times, a sign of our youth, our lack of funds and perhaps our lack of paternal guidance.”

Nobody knows who was the first writer but the name “Julio 204” began appearing in New York in 1967 and was an inspiration to many, who began imitating him, putting their names and street numbers all over their neighborhood. Their tools were bought (or stolen) markers and spray paint from Pearl Paint. “They called themselves writers, nobody called themselves artists,” says John Naar, British born photographer who is known for photographing graffiti and who appears in the film.

Taki 183

Taki 183, whose story features prominently, was a prolific writer, and unlike many of the others, he made his mark outside his home neighborhood and thus got on the mainstream media’s radar. Taki worked as a messenger in Midtown Manhattan and as he walked from dropoff to dropoff he spread his mark on the light poles and other objects in his path. “You could walk 40 blocks and see my name on every pole,” he said. The New York Times took note and interviewed him. “They interviewed Kissinger and they’re interviewing me,” he said, seemingly still shocked and bemused at his notoriety back then. Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine also interviewed the now soul-patch-ed elder statesman of graffiti.

Cornbread

Cornbread, the Philadelphia’s legend, also gets his due, as perhaps the originator in this city. Cornbread explains his nickname. He was in detention and got sick of eating white bread with his meals. Remembering his grandmother’s delicious corn bread, he stormed into the kitchen and asked the cook why he didn’t make cornbread?! The nickname stuck. This writer’s motivation was similar to the others. He felt like Zorro when he made his mark, he says, like a kind of street hero.

The issue of gangs and graffiti comes up and while it’s stated that most of the writers were not in gangs, some got involved and were swallowed up by the violent gang fighting of the era.

184. Circa 1973. Courtesy ROCKY 184

Hugo Martinez

If there’s a villain in the movie, it’s Hugo Martinez, an art educator at City College in New York and admirer of graffiti who wanted to put all that energy and pizzaz on canvas, show it in galleries, and generally monetize it. He gave the writers paper, canvas, paint and markers and they worked. There was a show and a commission for a backdrop for the New York Ballet. But Hugo apparently didn’t share the money from sales and the writers turned on him, beat him up and trashed the workshop. Hugo refused to be a part of the movie, so we don’t get his side of things.

The movie ends on an elegiac note, with Rocky 184 declaring for the democracy of graffiti. “The people themselves developed it. We were family to each other,” she says. Taki 183, who is seen today working at his car repair shop, gets the final word, “I’m glad it spawned artists. I’m proud to say I was an originator. I made my mark. I’ve been called a legend in my time. It doesn’t get better than that.” Of his life post-graffiti, the quotable writer says, “I’m glad I don’t carry a marker around. I’m always tempted to write.”

Wall Writers has its Philadelphia debut next Saturday, June 25, 7:00 PM, at International House. The screening will be followed by a Q&A and book signing with director Roger Gastman and special guests from the film. Tickets and Additional Information here.