Post by Andrea Kirsh

Lower East Side

Minsuk Kim’s pavilion of hula hoops for Storefront’s anniversary

Walking East from Soho to Little Italy, I passed the intersection of Lafayette St. and Centre St. I didn’t realize that small triangle has a name: Petrosino Park. A group of people were constructing a large igloo out of hula hoops that towered over the playground equipment in the tiny park, and almost stretched from sidewalk to sidewalk. It was obviously an artwork. (I returned home to find the N. Y. Times had a photo of it that day).

When I asked what was going on, I learned it was designed by the architect, Minsuk Cho, as a pavilion for staging events in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the nearby Storefront for Art and Architecture, one of my favorite institutions. Storefront began 25 years ago with a series, “Performance A-Z”; for their anniversary they’ve arranged 26 days of “Performance Z-A.” All the participants have a history with the organization and include the likes of Vito Acconci (who, with Stephen Holl, designed Storefront’s current gallery), Dan Graham, and Marilyn Minter.

Mike Nelson, A Psychic Vacuum installation

I was headed East, to Mike Nelson’s project “A Psychic Vacuum” at 117 Delancey St., sponsored by Creative Time (Nelson’s work is open Fri. – Sun., noon – 6, through Oct. 28). Arriving a bit before noon, I saw a small group assembling on the sidewalk of the last block before the Williamsburg Bridge, and realized I was at the right place (no number was evident). Louise Barteau Chodoff, who was taking a break after the closing of her own installation,”Grove” (see post) met me there. At noon the metal door lifted, we were given disclaimers to sign, then directed to an inconspicuous door to our right.

Mike Nelson, A Psychic Vacuum installation

We entered what was appeared to be the abandoned interior of a small coffeeshop, more forelorn and litter-strewn than the garages of my messiest friends. We proceeded through a narrow passageway in which a bit of abandoned duct-work spilled its guts on the floor, and found ourselves in a small room containing only an old bus bench and a few illustrations tacked to the wall. On either side of the bench were two doors, both unmarked; like an O. Henry story, we were forced to choose. We took the right and found ourselves in another small room occupied only by a private shrine on the floor, of the sort I associate with syncretic practices such as Santeria.

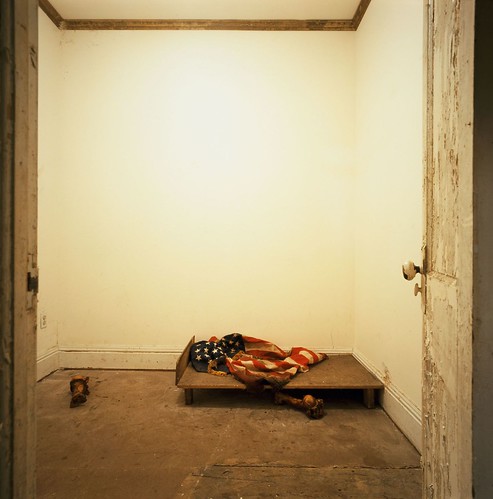

Mike Nelson, A Psychic Vacuum installation

It turned out that every room had multiple doors, so we proceeded through the second one and found ourselves in a passage adjacent to a small room with what appeared to be remnants of a violent event: a crumpled and bloodied American flag lay on the floor along with two cow’s (bull’s?) feet; two further bones were tucked behind the door. They had not been neatly cleaned. I haven’t yet mentioned that Nelson is a connoisseur of the effects of bad fluorescent lighting: the flickering and the ghostly pallor they induce. Throughout were battered fixtures of a piece with the variously grime-y walls, doors and ceilings.

Mike Nelson, A Psychic Vacuum installation

By this point the multiple doors and strange illumination had induced a sense of disorientation, exacerbated when we began to see one or another of our fellow visitors enter or exit in various directions. We would leave someone in one room only to find him appear in the next, but through a different door than we’d used; or someone from a group would exit one door as her friend entered via another. It resembled a Marx Brothers film, except the mood was not comic. We passed through a variety of passageways and rooms, a number of them filled with objects that implied the character and habits of their absent inhabitants (a bit like Ilya Kabakov’s “10 Characters,” but without Kabakov’s clearly-developed narrative). The progression of spaces was convincingly seamless–enough so that at one point a young woman asked how much of the interiors were extant (none), and how much were the artist’s interventions (everything but the peeling paint on a few, high ceilings).

I won’t detail the walk-in meat freezer, the room with prayer rugs, or the rest of Nelson’s fun house of urban detritus which is much subtler, and hence, creepier than Eastern State’s annual Halloween haunted house. You should discover it firsthand. I will say that in the last room, the only one with windows, we looked up and saw a bit of ribbon and the remnant of a foil balloon hanging in a tree. There was no way to know whether Mike Nelson had planned that, too.

I’ll have to skip all the art we saw at P.S. 1, as well as our minor detour to see Elizabeth Murray’s tile mural at the Courthouse Square MTA stop. I want to get on to the Asia Society.

Upper East Side

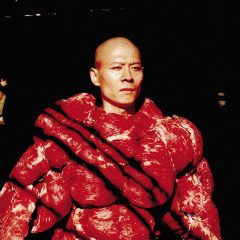

“Zhang Huan: Altered States” is the first retrospective of the Chinese artist who moved from Beijing’s East Village to New York in 1998, before returning to China in 2005 (the exhibition runs through Jan. 20, 2008). I had seen a number of his photographs in 1998, when they were included in “Inside Out: New Chinese Art,” also at the Asia Society). This time they were presented in the context of films of a number of performances which Zang did at more or less the same time. His art began with his body for many of the reasons that American women turned to performance in the 1970s: it was available and cheap; and also because in making his work coexistent with himself he had more control of it, and it inserted his entire being into the art arena.

Zhang Huan, “Family Tree” 2000

one of nine color photographs of performance, Amherst, New York

21 1/2 x 16 3/4 inches, collection of Larry Warsh, @ Zhang Huan, courtesy of the artist

But the photographs that arose from Zhang’s performances in no way resembled the crude documentary images that are artifacts of most artists’ performances (or Bruce Nauman’s various photographs of himself distorting his image or spitting water). Rather, they are large, lush and beautiful, and obviously composed. Some were single images, like the group of people standing in water up to their armpits in “To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond” (1997). Others charted the progression of a performance, such as “Family Tree” (2000): a series of head shots in which the features of the artist are sequentially obliterated as more and more of his face is covered with texts, written in black ink by three calligraphers.

Zhang Huan, “Ash Head No. 3” 2006 ash, iron and wood 18 x 17 x 17 inches

On moving to Shanghai in 2005, Zhang bravely turned his back on 12 successful years of performance and radically changed his art. His recent work involves a great deal of craftsmanship (wood-carving, welding, printmaking) and Zhang employs a large crew of assistants. His workshop is documented in an excellent film which is shown in an alcove beside the exhibition. Much of the recent work was inspired by a trip to Tibet, where the artist found fragments of large Buddhist sculpture, remnants of the destruction of the Cultural Revolution. He has recreated some of these fragments using the ashes of incense gathered from temples, transforming the residue of ritual into powerful testaments to faith.

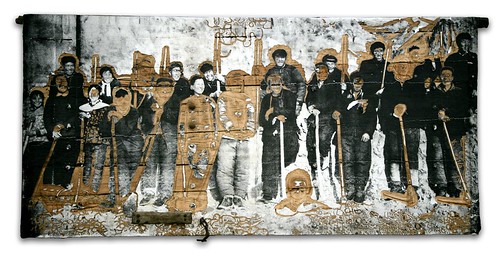

Zhang Huan, “Memory Door Series (Break)” 2006, woodcut with mixed media on wood

63″ x 135″, collection of Harold and Ruth Newman, @Zhang Huan courtesy of the artist

For the series, Memory Doors, Zhang affixed greatly enlarged historical group photographs to antique wooden doors. He then carved them, as if to create huge wood-blocks for prints. In the process some of the faces were completely gouged out, much as Stalin obliterated disfavored officials from photographs. This work traces the uncertainties of memory and historical records, and speaks easily to Zhang’s global audience.

(Libby: Some other posts on Zhang Huan on artblog–we’re fans:

- At the International Center of Photography “Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China” show

- Peace, a Creative Time-sponsored installation

- another comment on Peace)

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.