Pepon Osorio, Mangual, 2007, video a short video loop of a dark-skinned man vigorously, but unsuccessfully rubbing off white-face makeup–referencing identity and culture and art history all at once.

There’s some terrific work included in the exhibit From Taboo to Icon: Africanist Turnabout, an exhibit currently at the Ice Box, a group show of about 70 works that grew out of a series of symposia at Temple University last year.

The symposia, African Impressions/Contemporary Art, explored African influences in modern and contemporary art. They pondered the meanings behind the experiences of artists of color, especially when they used Africanist imagery. And they waded into the thicket of who owns the voices that get heard in the art world.

Earl Fyffe, Shanty, 2004, 4’3″ x 5’3 1/2″ x 3’6 3/8″, transforms specific, impoverished housing into a veritable god of safe housing, an animist form warding off the dangers of sliding down the slippery slope.

The exhibit at the Ice Box, interestingly enough, is full of work that has gotten seen and heard because of its excellence, changing times, and changing exhibitions spaces. Included in the show are artists who have crossed into the mainstream, like Hank Willis Thomas, Pepon Osorio and Deborah Willis.

As far as changing times go, I recently had a conversation with a friend about how the younger generation of successful African American artists, including his son, seem to be thinking about their work and their position in the art world without much consideration of race.

Sonya Clark, Beaded Prayers, 1999-present, 120 inches wide, 24- x 24-inch panels. An ebullient display of tiny, mixed media talismans of fiber, beads, toys, etc. I’m thinking mini-Adeagbo here.

And exhibition spaces are indeed showing more African-aesthetic art than ever before, thanks in part to the Studio Museum in Harlem and a younger generation running museum spaces. Martin Puryear’s African-influenced work closed last week at MoMA; the Whitney has increasingly been stepping up to the plate, as has the Met; and locally so has the Fabric Workshop and Museum. Inroads are happening.

But the curators statements show they want to push the inroads further. Others whose work stood out in the exhibit who indeed should be shown more widely include Sonya Clark and Earl Fyffe, for example.

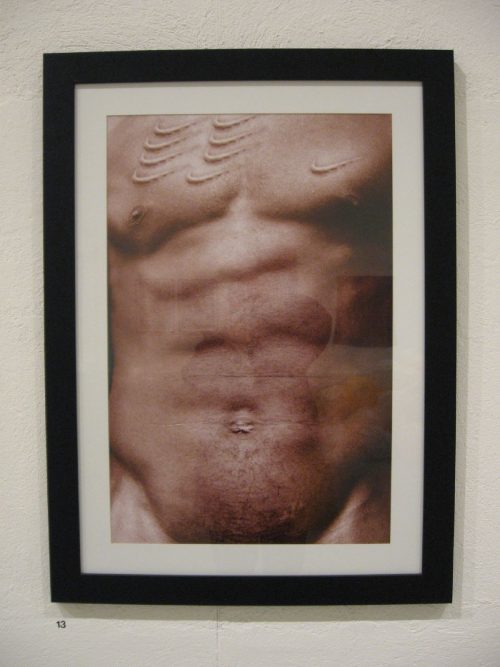

Hank Willis Thomas, Scarred Chest, 2002, 30 x 40 inches, photograph, places the commercial world of basketball and black athletes in the context of tribal scarification, bringing brand loyalty to a shocking level. We first saw work from this series in the Frequency show at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Here’s my short list of faves:

Pepon Osorio–Mangual

Earl Fyffe–Shanty

Sonya Clark–Beaded Prayers, a wall display of beaded pouches; and “Long Hair”, a 96-inch-long scrolled photograph of an equally long dreadlock

Betty Leacraft–Camouflage: A Means of Survival, an fiber-based altar

Ghariokwu Lemi–three gloriously colored Pop/graffiti anti-war drawings, including Lagos Sitty, by album cover graphic designer Lemi

Hank Willis Thomas–a couple of photos and a sculpture playing on basketball culture (I’ve seen all this work before, and I’m happy to see it again)

Betty Leacraft, Camouflage: A Means of Survival, 1992, 72 x 52 inches, mixed media fiber, a powerful piece about culture and identity that masquerades as anti-war. Leacraft incorporates materials as diverse as clothing, holy card reproductions, beads, photos, sticks, candles and written symbols and words.

All of these pieces are rich conceptually as well as quirky reflections of the times in which they are made. I can find something African about all of them, but mostly, what I see in them is contemporary art practice, which is gobbling up cultures from around the globe. I’m thinking here of the way that Georges Adeagbo’s Abraham—L’ami de Dieu installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art embodied the swirl of cultural objects and communications and ideas and threw it up on the wall and strewed it across the floor, representing a maelstrom of cultural migration and transformation.

Ghariokwu Lemi, Lagos Sitty, 2001, 22 x 15.75 inches, poster color, ink/pen. Things blow apart as people smile, love, live and die in close proximity in this small, compressed work–Basquiat on an acid trip

In addition to my favorites, other work also interested me for my usual reasons (i.e. making me think or just giving me something I want to look at). Among that group, I want to mention one of the videos (I saw only two of the four, but this one I loved) by Nadine Patterson–an amazing image of a dark-skinned dancer in a tropical red-and-white patterned shirt, moving in a penumbral space. The dark face and arms keep disappearing into the background, but the shirt floats and moves in a hypnotic, graceful way to a rhythmic, musical soundtrack. Very interesting and provocative.

The show, exhibiting work by more than 35 artists, includes a number by artists with local connections in addition to Osorio and Leacraft–Lonnie Graham (photo portraits), Deborah Willis (body builder portraits), Kimberly Camp (painting), Syd Carpenter (sculpture) and John Dowell (photographs). There may be more.

Andrea contributed a post on her encounter with one of the curators and one of the artists. Its got some great background information.