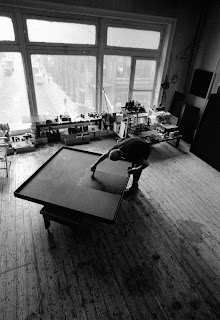

Ad Reinhardt in his studio, New York, July 1966.

Photograph by John Loengard/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

I attended the opening of an unusual exhibition at the Guggenheim last week: Imageless; the scientific study and experimental treatment of an Ad Reinhardt Black Painting (disclaimer: I wrote an essay for the catalog, but more on that later). It should interest anyone who is fascinated by Ad Reinhardt’s late, reductive works with their velvety qualities as well as painters, collectors and others with a serious interest in surface effects of paint.

AXA insured Reinhardt’s Black Painting, 1960-66 which was damaged during travel; they paid the full value and declared the work a total loss. AXA then donated it to the Guggenheim as a study piece and funded eight years of research on the painting by conservators and scientists at the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art under the direction of Carol Stringari. The exhibition and a catalog record the results.

Reinhardt went to great lengths to separate the oil out of his paints leaving them underbound and rich with pigment. He spread this customized paint onto the canvases with brushes so as to eliminate all record of their making. The black paintings in particular have even, uninflected surfaces; they were never varnished. The matte effect that Reinhardt labored to achieve is extremely fragile, betraying every fingerprint, minor scratch and other contact and the conservator’s usual methods of dealing with such damage is precluded by Reinhardt’s technique.

The study painting had been subject to more than one prior treatment, and a previous restorer had entirely repainted it to recreate the evenness Reinhardt sought. Not only is such treatment unacceptable to contemporary conservators who follow the standards of their professional association, but the repainting was done with entirely different paint and yielded an altered appearance. According to Stringari The surface had a plastic, reflective sprayed coating with a bluish-purple overall tonality. The subtleties and texture of the original painting had been obliterated…. Beyond the technical challenges are the ethical ones: there is no agreement about how to treat, exhibit or label monochrome paintings that have been damaged. To solicit broader opinions AXA funded an online discussion among conservators and a curator, art historian and dealer which I moderated and wrote up for the catalog.

Because the painting was deemed unexhibitable the conservators were able to try various experimental treatments involving lasers to remove the restorer’s paint, performed at facilities in Crete and the Netherlands. The exhibition includes the study painting (which records areas subject to differing treatments) and provides detailed documentation of paint analyses, treatment and historical background on Reinhardt’s technique and attitude to damage. Even more exciting for both general and specialist viewers, the museum has borrowed several other black paintings by Reinhardt for purposes of comparison. Reinhardts with repainted surfaces are regularly on exhibit elsewhere, but this may be the only chance to see one acknowledged and shown beside Reinhardt’s original surfaces.

This sort of research and discussion is rarely made available to the public and such subtleties of surface effect do not show up in printed reproductions. The Guggenheim is to be congratulated for allowing us to follow it. Reinhardt’s black paintings require significant time and concentrated viewing to appreciate; this exhibition provides a perfect background.