Art of Another Kind; International Abstraction and the Guggenheim 1949-1960 (through Sept. 12, 2012) is a collection of paintings and mostly modestly-sized sculpture by 70 artists from Europe, the U.S. and Japan; despite the title, Latin American artists are ignored. The works were acquired by James Johnson Sweeney, then director and curator of the Guggenheim Museum, in the decade preceding the opening of the Frank Lloyd Wright museum building. Sweeney stated that he was determined to acquire work by ‘tastebreakers,’ the people who break open and enlarge our artistic frontiers.

The period following WWII was rich in experimental art, encompassing Abstract Expressionism, Art Brut, Art Informel, COBRA, and work by artists such as Yves Klein and Piero Manzoni who stood apart from any of the formal or informal movements. The exhibition can certainly be enjoyed as one curator’s view of the period as well as a chance to see rarely-exhibited work from the Guggenheim’s splendid collection; so little of it is ever on view that I know mostly those works the museum has lent to exhibitions elsewhere.

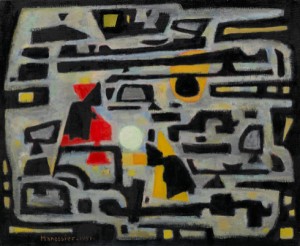

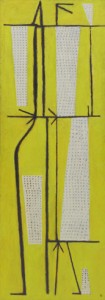

I’m usually more interested in seeing work I don’t know than a round-up of greatest hits, and this exhibition offers a fascinating selection. Some works are by artists whose names I know, yet I’ve seen so little of their work that I would be unable to identify them. But more interesting still is the number of good artists whose names didn’t even ring a faint bell: Antonio Saura (1930- 98, Spanish, whose monochrome grey painting with vestigial figuration looks remarkably current), Alfred Manessier (1911-93, French, represented by a small painting covered in a pattern whose intervals remind me of Adolph Gottlieb’s early pictograms), Jorge Oteiza (1908-2003, Spanish, two box-like, welded sculptures are exhibited that look at least ten years ahead of the period), Marc Mendelson (b. 1915, b. London, lives in Brussels, a fairly-large painting in a flat and graphic style), Étienne Hajdú (1907-96, b. Transylvania, d. France, an elegant, abstracted sculpture of a cock); and these are just a few.

Which made me think about about how artistic reputations are made, or lost. These are artists who gained enough attention in the 1950s that their works were purchased by a New York museum, admittedly at a time when “New York museum” didn’t have the significance it now has. Did the artists die young? Or stop making art? Did their reputations survive locally but not internationally in a period when air travel was not yet part of everyone’s life? Are there basements and store-rooms filled with their unknown work? Google searches and the Guggenheim’s excellent web catalog re-assured me that they all maintained respectable careers in their homelands. Of course, looking at the covers of art magazines of the past will reveal numerous other artists whose reputations have not survived. It’s sobering to think that museum acquisitions and cover-worthy art can have such short currency.

Jayson Musson, Halcion Days at Salon 94

Jayson Musson has given craft and commercial textiles a leg-up by reconfiguring a group of intricate machine-knitted sweaters as paintings (at Salon 94, July 11-August 17, 2012). His re-use not only accords with a more general re-cycling aesthetic, but also inverts the history of textile makers’ stealing patterns from artists, as Alexander McQueen did with Renaissance paintings; and who hasn’t seen versions of Warhols and Lichtensteins on someone’s back?

The textiles he used were made as sweaters by an Australian company, Coogi, which describes them as “wearable art.” To Musson, the patterns bear an obvious relationship to Pollock’s spontaneous paintwork. They consist of swirling patterns, characteristic of fluid paint applied to a horizontal surface; they also remind me of fair ground paintings, made by machines which squirt liquid paint onto a rotating surface. Musson is undoubtedly making a humorous attack on painting as a revered locus of cultural expression; but the joke is also that at a distance, Musson’s not-quite paintings look pretty damn good.