—Maeve’s trip to Newark, DE, unearths two interesting exhibits on the campus of the state’s big university.–the Artblog editors—————->

A treasure often enjoyed exclusively by University of Delaware staff and students, the UD Museums offer an enriching selection of diverse, well-curated exhibitions that is well worth the trek down to Newark. Of the three museums, the Mechanical Hall and Old College Galleries (including Old College West) focus primarily on the visual arts, while the Mineralogical Museum is dedicated to geological specimens. This review covers exhibits at two of the three museums.

Gertrude Käsebier’s Ground-Breaking Innovations in Photography

The Old College Gallery houses some of the most well-known pieces in UD’s permanent collection, including work by famous local artists Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth, as well as American 20th century, Native American and Pre-Columbian art.

Currently on view there is a whirlwind show of more than fifty prints by Gertrude Käsebier, an eminent 19th century photographer whose talent and resolve led other women to subsequently pursue photography as a full-time, income-generating career.

Käsebier’s work has not been thoroughly re-examined since the 1990s, when it was shown at the Delaware Art Museum. The UD Museums are uniquely suited to produce an exhibition critically analyzing her as a radical innovator, as they hold the largest collection of her prints next to the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY. A sizable archive also supplements and lends context to this work.

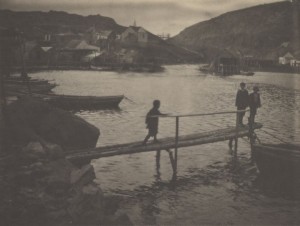

The Complexity of Light and Shade is a collaboration between Curator Stephen Peterson and the UD Conservation department, which worked on preserving and repairing the prints (a fascinating process that is well-documented in the catalogue). Of the prints selected for viewing from the 150 or so in the collection, there is a generous serving of portraiture, including mother and child scenes and intriguing images of well-known cultural figures. Also selected are a number of works demonstrating Käsebier’s experimentation with assorted printing processes, as well as her output from a sojourn in Canada.

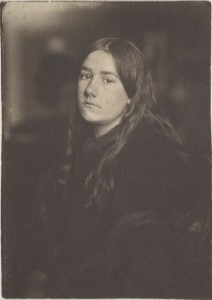

At the entrance is a group of the artist’s much-loved prints of women and children. Käsebier shied away from the customary artifice of studio portraits, instead preferring her subjects to appear at ease, without ostentatious props or backdrops. Her pensive photograph of her daughter Hermine embodies this natural, unprompted style, while also displaying the artist’s unique use of tonality and atmosphere. As Peterson points out, “although Käsebier’s prints are monochromatic, they are never merely black and white.” Her work is rife with resonance and emotion, echoing the emphasis placed on shadow by her contemporary, James McNeill Whistler.

Käsebier often played with a variety of printing processes and papers, resulting in different lighting, color and textural effects. Among the prints owned by UD, those produced from the same negative are often unrecognizable from one another. The photographer’s manipulation of negatives also made her an early critical examiner of the ‘real’ versus the representational. She was clearly quite aware of the complex relationship that a print has with the actual person or scene that it depicts.

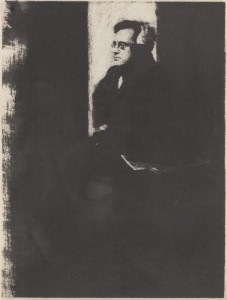

Peterson makes a point to pair prints together whenever possible to explore the different effects, notably of platinum as compared to gum bichromate. While platinum prints are smooth, without as much variation in light, gum bichromate has a rougher, more rugged feel (see “Untitled (Woman and Child with Horse)” — in the exhibit but not shown in this article — for a good example). Increased contrast highlights the subject in a less forgiving manner than the almost airbrushed look of more romantic platinum prints. In the case of “Mrs. J. Montgomery Sears,” gum bichromate lends a mysterious, beguiling element, augmented by the wild tornado-like effect that Käsebier added by manipulating her subject’s hat in the negative.

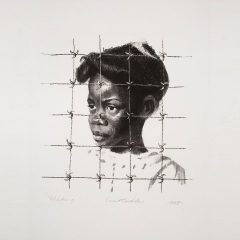

Among other luminaries of the time (Auguste Renoir, Baron de Meyer, Rose O’Neill for example), Käsebier especially favored photographing the painter John Sloan, who encouraged her many printing tests. Eight of these inventive works are on display, many of them scratched, swirled and printed on unorthodox materials— tissue paper in particular. One (reproduced above) is so pixilated-looking that it could be a chalk drawing or a rough woodcut.

At the very end of the show are a series of Käsebier’s Canada landscapes— less innovative than her portrait work, these scenes are interesting compositionally, but lack an experimental edge.

Gertrude Käsebier: The Complexity of Light and Shade, to June 28, 2013. Old College Gallery, 18 East Main St. Newark, DE 19716.

In/Visible Seams – Fatimah Tuggar’s Investigation into Socially-Constructed Representation

The Mechanical Hall Gallery hosts the university’s preeminent collection of African American art, drawn from a donation of approximately 500 works from Atlanta-based collector Paul Jones. This gallery is also a space for stand-alone shows related to the African diaspora, such as the current retrospective of Nigerian-born artist, Fatimah Tuggar.

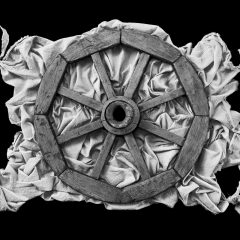

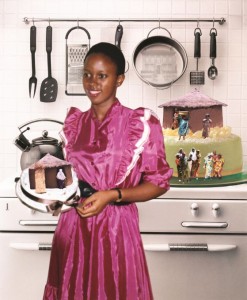

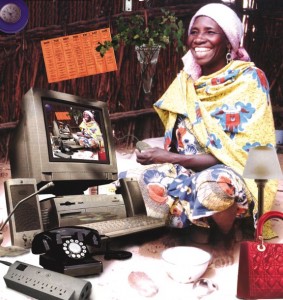

Tuggar is most well-known for her jarring digital manipulations, in which she pairs both real and artificial imagery in order to draw attention to sometimes distasteful societal truths. In/Visible Seams, organized by Curator of African American Art, Julie McGee, includes eighteen of Tuggar’s signature computer montages, as well as an assemblage, “Tum Tum and Tabarma” and a video collage, “Fusion Cuisine.” Taken as a whole, Tuggar’s body of work presents us with a startling, and quite clever, inquiry into the pervasive effect of technology and media on our daily lives, most notably in our perception of women of color.

A conspicuous feature of the exhibition is the deliberate lack of explanatory wall text— the artist does not wish to mediate visitors’ individual experience. Accordingly, McGee does an excellent job of drawing attention to Tuggar’s occasionally disturbing image pairings while still leaving final evaluation of the work open to diverse interpretations.

“Working Woman” is a prime example of Tuggar’s method. A depiction of a smiling African woman in an atypical office setting, this montage creates an incongruous coincidence of stereotypically ‘old’ or ‘backwards’ elements and indicators of modernity. Tuggar identifies her subject as a professional by providing us with a panoply of symbolic tropes, including a full calendar, a desktop computer, a telephone and a red ‘power purse.’ The artist then disrupts our unconscious consumption of this image by including several illogical signs. The woman’s haphazard hold on the mouse, for example, the miniature floating lamp, and the lack of wall outlets for her many electronics all point to the impossibility of the situation. Moreover, the outdoor setting, complete with woven walls and a mat rather than a desk hint at an awkward conflation of divergent cultural traits. As a result, our traditional signifiers of “African,” “Western,” “female” and “professional” identities are rendered humorous and ineffective, and viewers are pushed to reexamine their understandings of these social constructs.

“Voguish Vista,” the most recent computer montage in the show, integrates photographs taken by Tuggar in Harlem with imagery culled from magazines and the internet. What looks at first sight like a normal storefront is in fact a powerful commentary on the ethics of global consumerism. In the glass showcase of a local American Apparel store we see the echoes of the Occupy movement reflected back at us, the slogan “the 99% will not be silenced” interrupting our easy intake of the slim, stylish mannequins with the reality of our inequitable financial structure. Perhaps also a reference to American Apparel’s harassment of young female employees, pressuring them to pose for risqué photographs, this print hints at the deeply pernicious undertones of the fashion industry. Moreover, the latter’s flattening effect on local culture is evident in the two stale ‘African’ outfits on display, with one garment drawing upon President Obama’s likeness to better appeal to an American audience.

In/Visible Seams closes May 12. Mechanical Hall Gallery, 30 North College Ave. Newark, DE 19716.

Playing with Perception

Both Käsebier and Tuggar push against norms of image making in order to produce their own versions of reality. Just as Käsebier manipulated her negatives to explore the variety of ‘truths’ that a photograph could produce, Tuggar combines the synthetic with the real in order to bring to light artificial social constructs. UD has selected a good team of curators to bring a new critical eye to excellent, yet previously under-examined work.

All images courtesy of the University Museums, University of Delaware.