[Andrea visits a recent show focusing on the close friendship and artistic interchange between Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt, including some unexpected deviations from the work we’re all familiar with. Then, she stops off to view Titian’s “Danae”. — the Artblog editors]

Degas/Cassatt, which was on view at the National Gallery of Art through Oct. 5, was a triumph of an exhibition, tightly conceived around ideas and artworks exchanged by the two artists in the early years of their friendship. I must admit that I had no interest in the exhibition before I saw it, thinking I knew the work of both artists sufficiently and suspecting that Degas would overwhelm his American colleague. But Cassatt had never looked better, and I suspect she never will, than during this period when both artists learned from and inspired each other.

Explorations in media and approach

The exhibition is smartly limited to four modestly-sized galleries, each of them focusing on a single theme. This enables viewers to give sufficient attention to the many sequential developments of ideas across drawings, paintings, and prints done in a melange of intaglio processes: etching, aquatint, drypoint, roulette, and two show-stopping, color monotypes by Degas. If you don’t know his landscape monotypes, in which one of the consummate draughtsmen of all times renounces drawing completely, they alone are worth the trip to D.C.

Surprising methods and influences

The exhibition itself developed from research shared by Kimberly A. Jones, curator at the National Gallery of Art, and her colleague, Ann Hoenigswald, a conservator. Notably, the catalog includes their joint essay, rather than the more usual format of a curatorial writing at the beginning and technical information confined to an appendix or essay positioned at the back of the catalog. They were able to determine that one of Degas’ soft, smudgy ballet scenes (Sheldon Museum) was executed in egg tempera–although it resembles pastel, and during the period of their intense interaction, Cassatt occasionally painted with aqueous media: distemper, which is bound with glue, and gouache, an opaque watercolor.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the exhibition is the large (50″ tall) painting by Cassatt (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Ft. Worth) that is almost Symbolist in its generalized forms; it was lightly painted with distemper, with small areas of metallic paint. While Degas was known to be experimental in his technique in numerous media, it was previously thought that Cassatt used conventional painting technique.

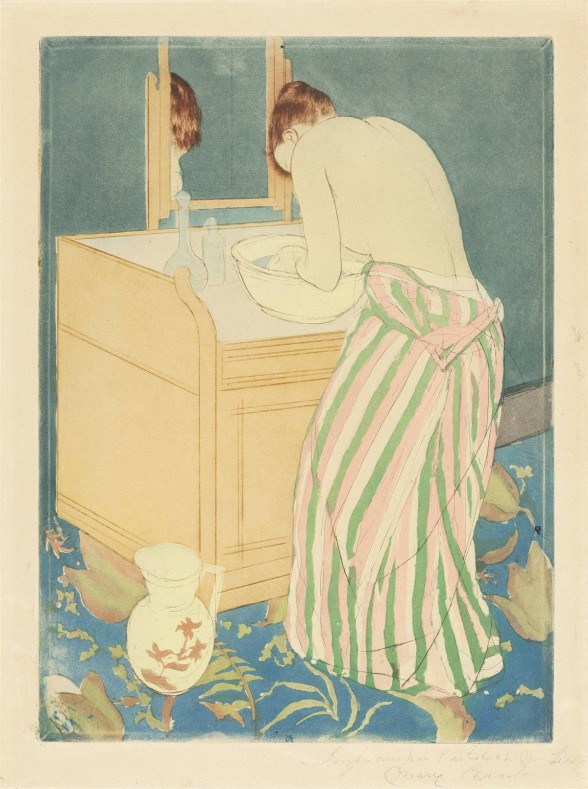

While Cassatt’s color aquatints are without precedent or heirs, until now, few realized that from the moment she took up printmaking, she achieved results from innovative methods that influenced Degas. The exhibition includes numerous examples where each artist owned the most unconventional, and at times unresolved, artworks done by the other, confirming their interest in each other’s most experimental work.

Degas’ many versions of Cassatt and her sister visiting the Louvre, which include paintings, drawings, and prints, constitute his most sustained exploration of a single subject. Cassatt is shown from behind in hat and nipped-waist jacket, leaning on her umbrella as she contemplates the art. Her sister, seated several feet away, reads a guidebook. Museums were among the few public places that upper-class women, such as Cassatt, could go without male escorts. Alas, the Louvre no longer provides benches in the galleries, but this was before mass tourism spoiled much of the art-viewing.

Titian’s “Danae” and the start of a tradition

Titian is my favorite painter, and the one who invented grand paintings of erotic subjects in Renaissance Italy. If he created a sexier image than the “Danae” (from the Capodimonte Museum, Naples, on loan to the National Gallery of Art through Nov. 2, 2014), I can’t think of it. Danae’s face is shadowed and the spotlight is fully on her naked torso and legs. The young woman, bejeweled and looking more accepting than aroused, spreads her thighs to receive the king of the gods. Cupid, seeing his presence is neither needed nor welcome, rushes off at stage right as Jupiter appears in the guise of the ultimate, male fantasy of sexual conquest–pure ejaculate turned to gold. This certainly beats the disguise as a friendly bull that he used in seducing Europa.

Vasari reported that Michelangelo, who saw the painting in Titian’s studio, thought it showed weak draughtsmanship. It is true that the great Venetian painted some splendid works where the drawing is weak–the Fitzwilliam’s “Tarquin and Lucretia” comes to mind. But I don’t consider this one of them, and it never really matters. Michelangelo thought that understanding of anatomy was primary, but it was musculature and skeleton that he studied. Titian was all about the feel of skin and the seductive appearance of flesh, and his nudes, significantly, were almost entirely women. The painting invites the visual caress of Danae’s rounded, right underarm, erect nipples and softly yielding belly, buttocks, and thighs. As she draws back the bedclothes, the fingers of her right hand intertwine with the sheet, suggestive of the sexual act to come.

The painting was commissioned by a cardinal, Alfonso Farnese, a notorious womanizer and the grandson of a pope; celibacy was clearly not a stringent requirement for the 16th-century clergy. The National Gallery of Art owns a wonderful portrait of his younger brother, Ranuccio, painted when he was only 12. It is surely one of the most searching and sober depictions ever of an adolescent boy. I strongly recommend that any visitors who find the portrait of Ranuccio also look at the imposing portrait to its left, of Doge Andrea Gritti. Anyone who loves painting will marvel at Titian’s handling of the Doge’s golden cape, where at close range, the suggestion of the jacquard fabric dissolves into pure, creamy paint. This is the beginning of the Western tradition of luscious paintwork, taken up by Rubens and Velazquez, continued through the work of De Kooning and his colleagues, and maintained in the present by painters such as Amy Sillman and Cecily Brown.