[A.M. reviews a religion-based show that takes on major themes in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, offering hefty, personal pieces as well as lighter, wittier works. — the Artblog editors]

And the Word Is… exhibition has a second life at the Gershman Y in Philadelphia.

This project was first presented at the DCCA in Wilmington, Delaware in 2013, and its incarnation at the Broad Street venue is a breath of fresh air. Presented in the main gallery, a quaint space of 1,140 sq. ft., the exhibit is intimate and accessible, focusing on work that relates to religion and spiritual concepts from Christianity to Islam. The artists and artist teams are engaged in balancing acts between concrete or, at times, ironic inferences to religion and spirituality. These notions are integral to each entity’s conceptual blueprint. Words and text possessing religious connotations are amply explored in this exhibit, alluding to their power.

Sight struggles and signage

David Stephens conveys in Braille on wood plaques the last words of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane; however, the Braille is too large to be legible by those versed in the language. Therefore, the context of the work may rest in the artist’s own struggle with being blind and his encyclopedic knowledge of biblical subjects. Stephens builds his own archetypes, in plastic form, which bridge his philosophies about things spiritual and his lived experiences. However, of special note is a 2009 New York Times article about how Braille in this technological era is considered arcane. Stephens’ work could be viewed as a testament to this fact, while at the same time preserving its form.

These artists handle biblical and Qur’anic text, the subject of scribes through the ages, as fodder for consideration within and outside of their personal worldviews. The viewer is able to glimpse many of the artists’ regard for these spiritual concepts and texts, in spite of Stephanie Kirk’s photographs of public church signage, which seem created in parody or intended to elicit snickers.

Kirk’s recording of this type of text is compulsive, as is the work of Martin Brief, who extracts the word “God from titles listed on Amazon. The elegant results of his endeavor on large sheets of white paper are further enhanced by fastidious handwritten script.

Literal works

Influenced by her grandfather, Carole P. Kunstadt takes the book of Kings and the five books of Moses and meticulously constructs manuscripts that do not open. The words are carefully locked within precious containers of gold leaf and thread and Gampi tissue. Fragile and compelling, these books beg to be handled; yet their fragility precludes this possibility. Books that do not open may be frustrating for the viewer; however, it is the construction itself that serves as a visual clue to the power of the text and subject matter.

Additional word-focused art can be found in Johanna Bresnick’s and Michael Cloud Hirschfeld’s piece “Tigers of Long Island,” part of a larger work, Mamzer Loshen, which literally translates as “bastard tongue”. “Tigers of Long Island” is a standalone paper installation of words such as “gout,” “ulcer,” “Death of the First Born,” and “locust,” referencing plagues from antiquity to modern-day conditions that, if viewed through an ethnic lens, may pertain to assumptions about Jewish identity in how they are viewed or discussed. This white paper installation comprised of barely intelligible cutouts cascades and tumbles across the floor. The overall impact is playful; yet the weight of the work’s content is obfuscated. Maybe this is the intent of the artists, who describe themselves as “modern Jews of dubious faith”.

Another work by Bresnick and Hirschfeld, “Mouth to Mouth,” is a mound of gel capsules containing shredded text from Leviticus, which addresses the proper way to worship God and includes passages on homosexuality. “Mouth to Mouth” alludes to the ingestion of meaning. Tongue in cheek, it is quite witty.

Stories and sins

In an era of irreverence, these artists, perhaps suspicious of the religious practices that may have marked their childhoods or early adult lives, bring to the display an renewed appreciation of the power of words from antiquity–whether challenging or embracing religious text. What is missing is text that references other world religions. However, Sandow Birk’s “American Qur’an” is based on passages from the Qur’an.

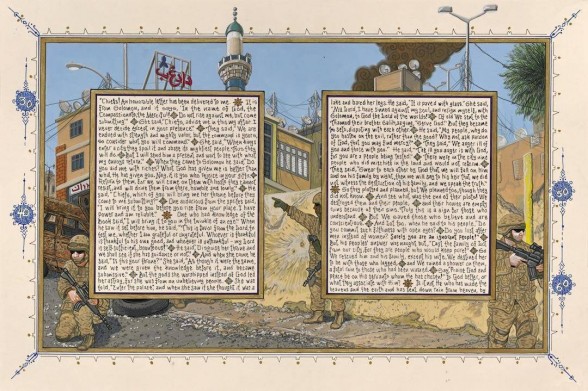

Panel B: We see American soldiers in Baghdad. (The neon sign in the background reads “Baghdad”.) In the parable of the Ants, the ants, who are numerous, go into their homes to hide from the army of Solomon, though Solomon claims he is benevolent. Birk’s image is a metaphor of the Americans in Baghdad and the Iraqi civilians, who are hiding from them and their more powerful army.

Birk’s American Qur’an pairs text and imagery to illustrate scenes from contemporary American life that coincide with holy Arabic text. In some instances, these illuminated pages straddle the realm of reverence and impertinence.

Also in the show is Nicholas Kripal’s word-based floor piece. In researching the etymology of the words “epiphany” and “lust,” both words found in the book of Matthew, Kripal decided to construct the words in low-relief metal boxes, filling one with salt and lining the other with copper. Installed in this show are the boxed letters for “lust”. Denoting intense desire and considered one of the Seven Deadly Sins, Kripal’s copper-lined, boxed letters reference copper’s association in Ancient Rome with cash, coin, or wages.

Viewers are bound to enjoy the wit, intimacy, and conceptual interpretations of religious passages in this exhibit. It gives one something to contemplate well after the visual experience is over.

And the Word Is is on view at Gershman Y from January 22 – May 14, 2015.