[Irena tours a show of artist Horace Pippin’s work, which set the African-American artist apart during a time when racism threatened to overshadow his talent. — the Artblog editors]

West Chester, Pennsylvania, about an hour outside of the bustling grime of center-city Philadelphia, is a small slice of leftover nostalgic Americana. At 327 Gay St., a private residence, stands a historical marker. It is the only clue within the immediate area to suggest that in 1888, West Chester produced this country’s first nationally recognized African-American artist.

About Horace Pippin

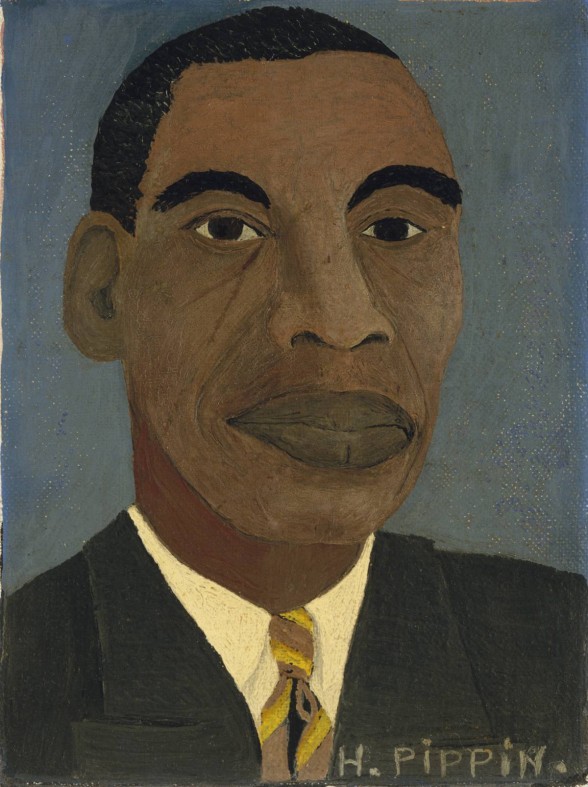

Horace Pippin (1888-1946) is considered to be one of the most important black artists coming out of the generation immediately following slavery. In his youth, Pippin lived through segregation and other accompanying hardships. As a young man during World War I, he served in the famous 369th Infantry, the Harlem Hellfighters, made up of black and Puerto Rican soldiers fighting in Europe. His time in the Army affected him deeply, as evidenced in a personal journal filled with war-related sketches and monochromatic paintings of life as a soldier. He was wounded in battle, and developed his artistic talent as he nursed his injured right arm.

Pippin’s unlikely artistic legacy is made up of vibrant, carefully detailed oil paintings that maintain both a folk mentality and a sophisticated artistic competence. They can be discovered in the Brandywine River Museum‘s major summer retrospective, Horace Pippin: The Way I See It.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A blend of comfort and strife

The show, organized by Brandywine associate curator Audrey Lewis, is arranged according to the differing periods of Pippin’s subject matter. Lewis, who kindly gave me a tour of the exhibition space, offered her insight on the development of his autonomy as an artist and his awareness of the evolving world around him. She pointed out that Pippin leaps from early representations of landscapes, interiors, and portraits to blunt themes of race, war, and social injustice. His connectivity with the viewer transforms, as his earlier pieces are primarily aesthetically driven, while his later works blend narrative and complex symbolism.

Pippin found his eventual voice through visual conversations on racism in America and the black experience. The Way I See It exhibits over 60 pieces on loan from various collections and museums, and the exhibition’s breadth demonstrates his artistic complexity and sensitivity.

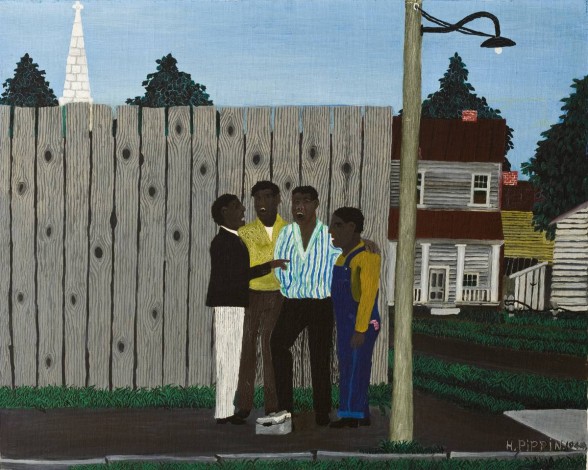

Luckily for West Chester, Pippin paid some homage to his hometown (although he did spend a good portion of his youth in Goshen, New York) with images of daily life as he once knew it. Simple scenes of small-town life, like that in the painting “Harmonizing,” are peaceful glimpses into Pippin’s adolescence and are also very much representative of the African-American experience in the first half of the 20th century. Pippin’s life under segregation and the isolation of black communities at this point in history likely shaped some of his poignant imagery of dynamics between family and friends.

oil on fabric, 24 1/8″ x 30 3/16″, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Pippin’s interior scenes are also something to behold, such as the 1944 piece “Interior” (a.k.a. “Interior of a Cabin”). There is a nostalgic sadness in the representation of home and family and in the lack of interaction between the figures, but there is also a certain level of comfort and intimacy. According to Lewis, one of Pippin’s most consistent qualities was his ability to carefully harmonize joy and sadness and bring together the highly personal with the observational.

In an immensely different type of interior–the piece “Victorian Parlor”–some Impressionist influence can be noted in the portrayal of flowers and the skewed perspectives of the furniture. Around 1940, Pippin had briefly enrolled in art classes at the Barnes (though he discovered them to be less than stimulating) and while in the company of Albert Barnes, enjoyed the works of artists such as Cezanne and Renoir. Albert Barnes went on to collect many of Pippin’s works and to champion his career, and his collection today includes some captivating examples of Pippin’s domestic interiors and imaginative scenery.

Well-deserved legacy

Pippin’s success began when he was exhibited in the 1937 Chester County Art Association annual exhibit and gained the attention of influential local artist and illustrator N.C. Wyeth, who backed Pippin throughout his career. At 42 years old, Pippin became a national hit, earning solo exhibitions and other kinds of national attention. For a black artist at the conclusion of the 1930s, especially one who had received little to no formal training, his success was exceptional. Other African-American painters, such as Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000), were slowly chipping away at the segregating walls of the Western art world while Pippin was active, but progress was slow. Lawrence made specific reference to historical events affecting African-Americans, like in his Migration Series, and went on to cite Pippin as an influence.

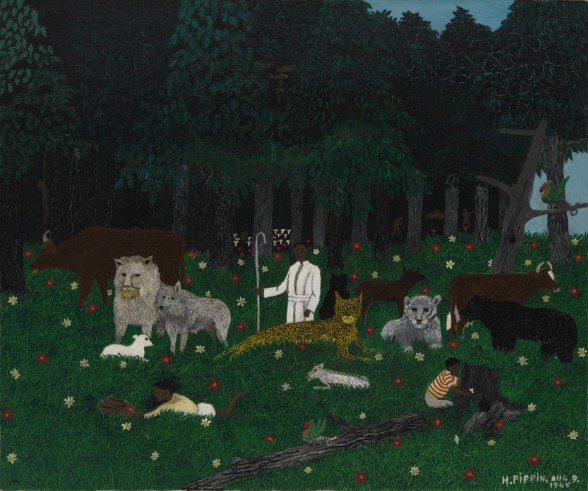

It isn’t easy to categorize Pippin, and giving him the all-too-vague label of “self-taught artist” can overshadow his immensely technical and innovative approach to his subject matter. “The Holy Mountain III,” one of a small series inspired by Edward Hicks’ “The Peaceable Kingdom,” is a good example. The scene depicts a utopia; however, in the corner, a shadowy silhouette of a body hanging from a noose can be made out, along with lurking soldiers between trees. The muted images of a foreboding evil that haunts the background of the otherwise peaceful scene are very telling of the complex manner in which Pippin approached his art. Despite the darkness of the imagery, which alludes to his time in the Army and his direct knowledge of violent racism in America, Pippin’s engagingly whimsical painting technique still allows the viewer to connect and interact with the piece. Pippin’s work is welcoming, even in the most uncomfortable of circumstances.

The current showcase of Horace Pippin’s work is not only opportune–at yet another pivotal time of American conversations on race and the importance of African-American history–but significantly well deserved. Sometimes, art visual culture is the best way to understand the past, and through Pippin’s firsthand recollections of American history, we find ourselves in the presence of not only a great artist and trailblazer, but a history teacher.

Horace Pippin passed in 1946 at the age of 58, so the success he found was unfortunately not lengthy. However, the legacy he left behind remains vibrant. His social commentary, his visual remarks on loneliness, joy, comfort, and nostalgia, and of course, his technical skills are rightfully remembered as some of the best in early American art.

Horace Pippin: The Way I See It is on view at the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadd’s Ford, PA through July 19, 2015.