Live and Life Will Give You Pictures, the very first exhibition of photography at the Barnes Foundation, provides parallel and complementary views of many of the scenes portrayed in the foundation’s storied permanent collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. The sprawling collection of masterworks by iconic French and French-influenced photographers is an exciting historical exhibit and its relationship with the Barnes collection is almost uncanny.

The exhibition is distilled from the incredible personal collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg and includes works by such masters as Eugéne Atget, Brassaï, Ilse Bing, André Kertész, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Many of the photographs that made me fall in love with this medium in the first place are here, and to be surrounded by the vintage prints and engulfed by well-curated conversations between them is a privilege.

Organized into seven rooms, each with its own theme (Street Life, Commerce, Labor, Leisure, Celebrity, Paris and Environs, Reportage, and Art for Art’s Sake), the work is skillfully arranged to provide snapshots of this creative era and its larger societal context. There is deft curation, both within each theme and within the show as a whole.

The city of light

With Paris at its heart, France was a bastion of creative energy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Painters like Monet, Matisse, Renoir, and Van Gogh nurtured an entirely new avant-garde mentality and aesthetic in their paintings, reaching ever more unlikely artistic heights and breaking from traditional parameters of composition and subject matter. They found inspiration in the streets as well as the fields, no more shying away from the grit and grime of the city and its inhabitants for the comfort of the studio and imagined classical idyllic scenes.

Photography and its practitioners–working at the same time as the painters–followed this same trend, continuing a creative dialogue between photography and painting that had evolved from pictorialism. Seeing the Barnes’ permanent collection in juxtaposition with the works in Live and Life Will Give You Pictures offers a view of the rich exchange that took place between these artists, many of whom drank and consorted with one another at the same cafés and nightclubs in the city of light.

The exhibition begins with the room “Paris and Environs” and the work of the city’s most famous early documentarian, Eugène Atget (1857-1927)–a fitting way to get out of the gate. Atget found himself in Paris at a fascinating and pivotal time of modernization, where maze-like medieval streets gave way to wide boulevards and public parks. Taking note of the city both vanishing and being reborn all at once, his large-format images of storefronts and shadowy back alleys, details so often overlooked, birthed the genre of street photography. Also included here are the haunting and nuanced night photographs of Brassaï (1899- 1984), gorgeous visions of the dark and shrouded underbelly of Paris, each one as evocative and filled with narrative as a film noir movie. The rich tonal and textural quality of vintage chemical prints–one of the best features of the exhibition as whole–is especially visible here.

Life, leisure, and work through the camera’s lens

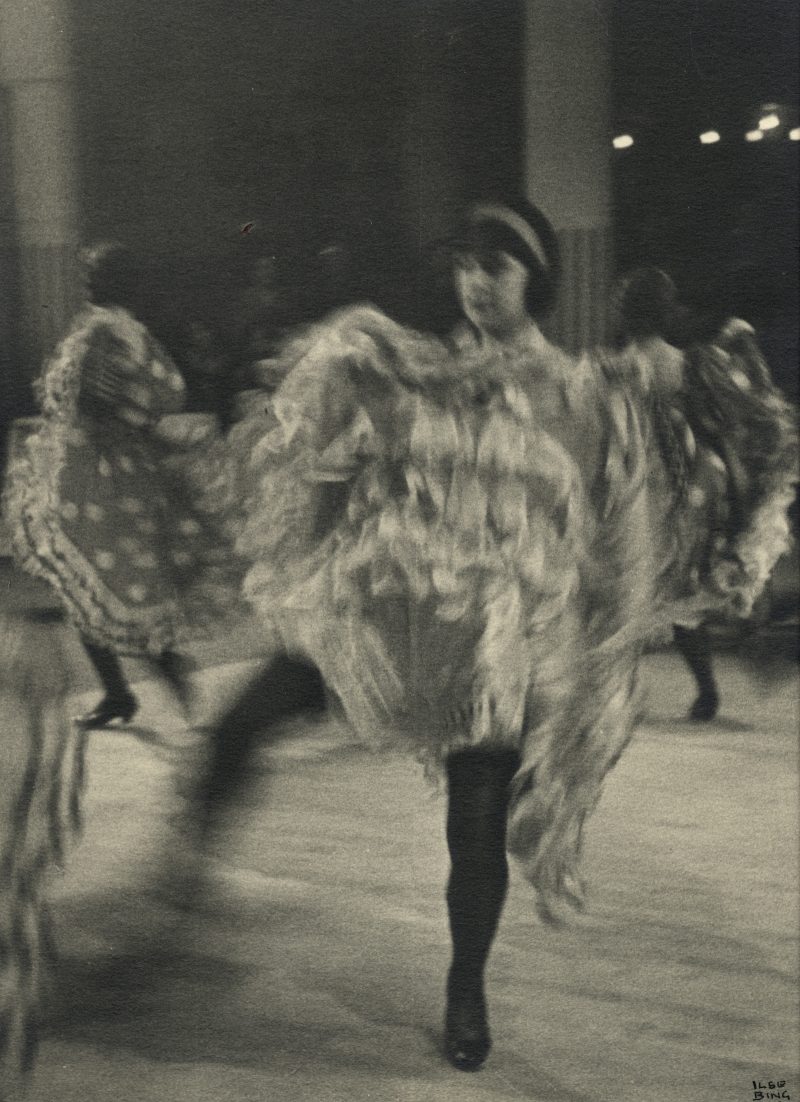

The following section, “Street Life,” is where we see full creative momentum of this era blossom, facilitated in part by the creation of new photographic technologies. The mammoth large-format cameras of Atget and Brassaï, while still occasionally used today for the quality of their negatives, were simply too heavy and imposing for the nimble work of the photographer on the street. As the speed of city life increased thanks to the subway, automobiles, and industrial revolution so, too, did the need for a camera that could keep up–and keep quiet. The handheld Leica camera, produced in Germany and championed by Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004), answered this call. The camera produced masterpieces by Cartier-Bresson and Ilse Bing (1899-1998) (a photographer brought back into the limelight largely thanks to collectors Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg, according to curator Thom Collins). Crowd scenes mixing the social classes were popular and Cartier-Bresson’s capture of dogs mid-coitus is wry and raucous, whereas Brassaï’s “Two Toughs in Big Albert’s Gang” is raw and tense with a charged sense of tension and dynamism that pumps palpable energy into the room.

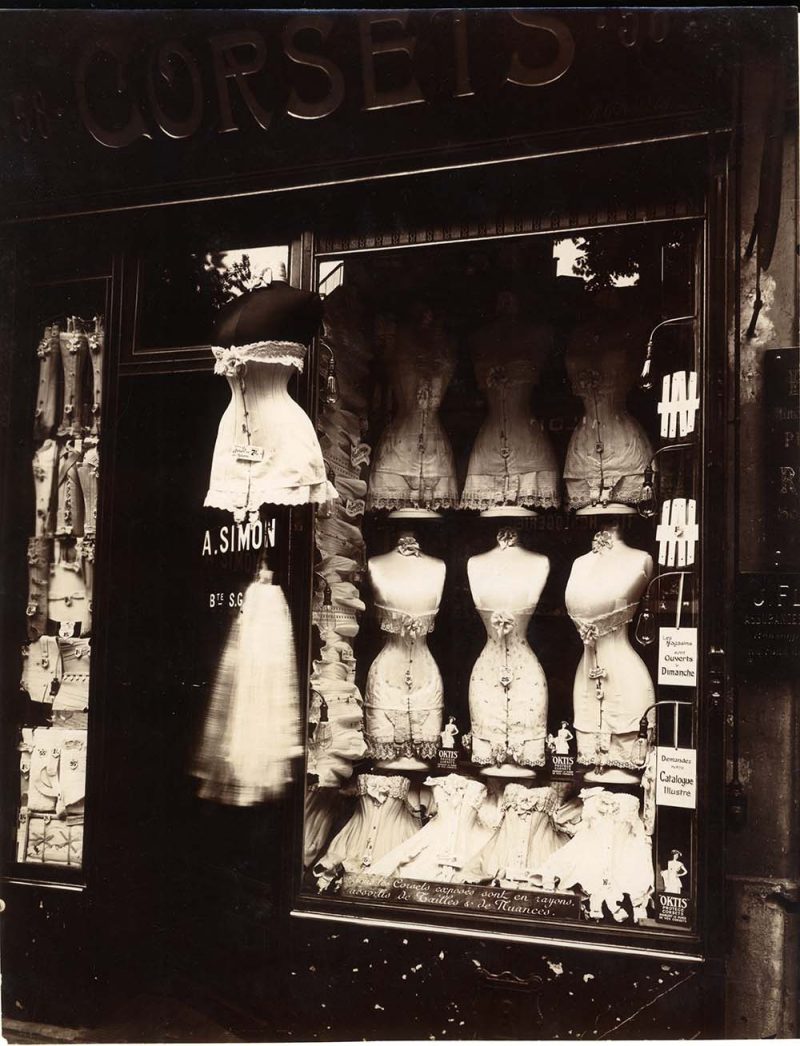

The following groupings–”Commerce” and “Labor”–highlight contrasting facets of modern life. The themes allow for an examination of the age of commodity and mass production from the front and back end, championing both the laborer and the consumer in an ever more aesthetically oriented age. Where Impressionist painters found merit in painting farm hands and postmen, so did photographers fix their lens on heroic labor and those whose hard work forged society forward. “Labor,” of course, does not entail just factory workers. Featuring heavily here are workers of the night–from prostitutes to sanitation workers active in the late hours of the city, so often neither seen nor heard and yet omnipresent behind shut doors and in subterranean sewers. Photographers had the ability to democratize workers of all kinds with the lens, seeing all work as equally deserving of both scrutiny and appreciation.

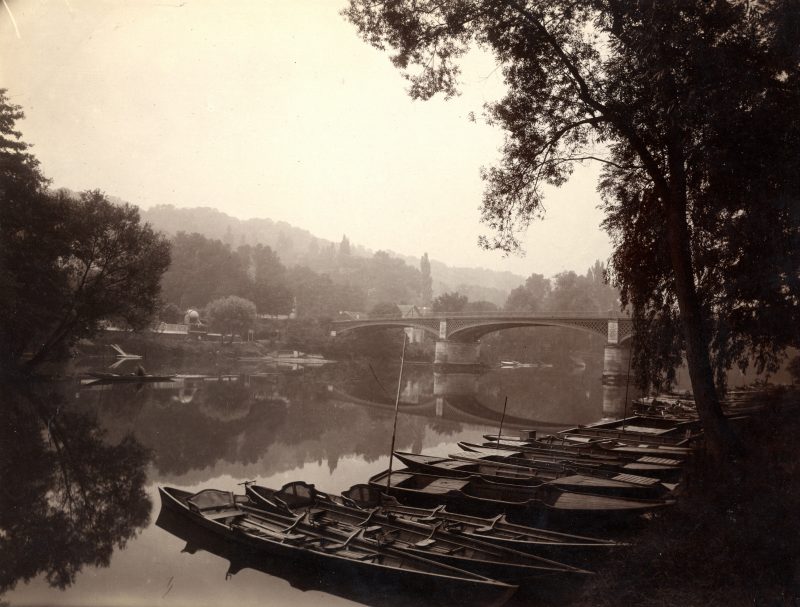

One of the more playful rooms is, naturally, the one addressing leisure in a culture with a blossoming middle class, eager for fresh pastimes and ways to spend newly awarded free time. It is no coincidence that the growth of café culture, dance and theatre, and working-class escape happened at the same time that France legally required employers to give employees paid time off. Photographers saw playful energy and unabashed relaxation all around them and captured small moments of tranquility or bliss amidst the squalor of the city and modern life–motifs mirrored especially by Renoir and Georges Seurat. One especially clear example is Seurat’s paintings and Cartier-Bresson’s photograph of residents relaxing on the banks of the river, watching boats float by in tranquil bliss. They are almost the exact same scenes, one on canvas and the other on film.

Photography and painting

The room “Reportage,” occupied by over a dozen original Cartier-Bresson prints depicting crowds, champions the colloquial and pedestrian over the stately and popular, another example of the democratizing effectiveness of the camera in the hands of an always curious and ceaselessly attentive master.

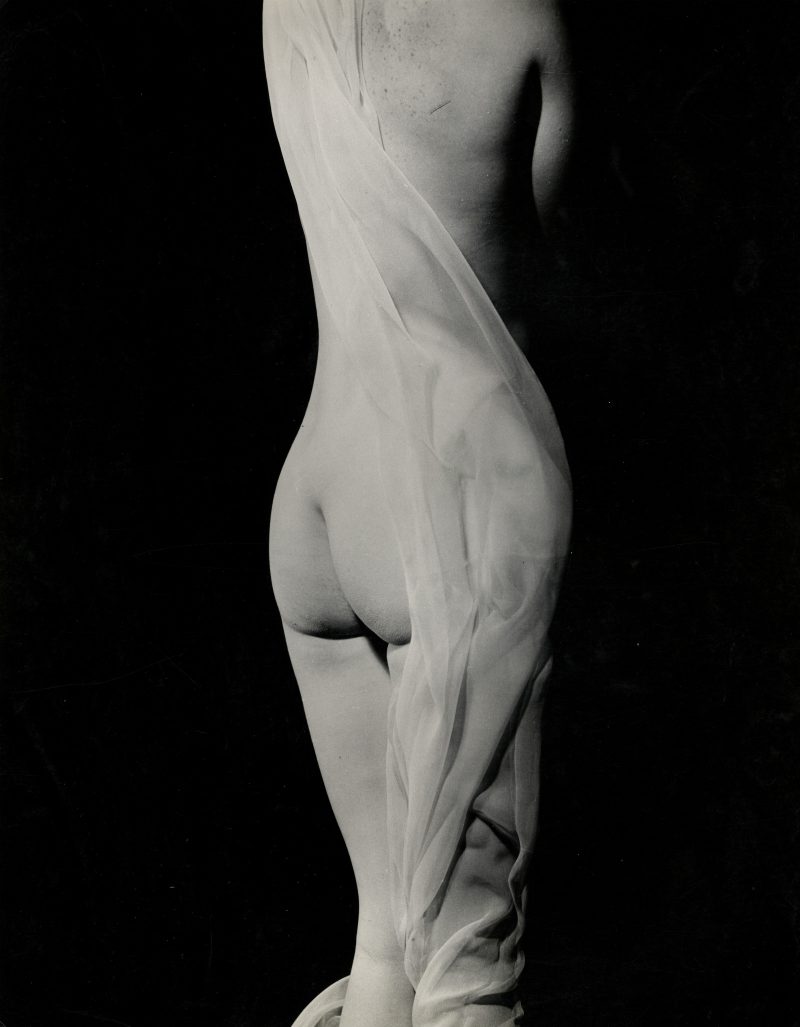

The “Celebrity” room adds a frisson of voyeurism as we see photographs of famous writers, poets, actors, and painters like Matisse and Picasso, many of whom are represented in the permanent collection. The room “Art for Art’s Sake” provides “painterly” photographs of nudes and still lifes as well as some abstract images and reminds you where you are–very close to the Barnes’ collection of Parisian paintings. The wide array of artists and styles here feels a bit scattered compared to the poised organization of the rest of the show, but the room acts quite effectively as a physical and ideological bridge between the visiting exhibition and permanent collection.

For anyone who has seen pictures by Atget, Brassai, Cartier-Bresson, and others of the era only in their history books or occasionally on a gallery wall and struggled to see their relevance today, this exhibition will reveal the photographs’ timelessness and clear historical relevance. The photographs and their makers matter because their influence is all around us–in the street photography that is so prevalent today, and even in today’s young photographers’ return to large format camera use and chemical processes in the darkroom. I learned about these masters when I was young and to see these works together and in the context of the Barnes collection was an exhilarating experience. For those who don’t know the photographs but who love the paintings of the era, the exhibition will be a revelation. The call and response between these photos and the paintings nearby is almost audible.