Moving between Dawoud Bey’s Harlem, USA, and Shawn Theodore’s The Church of Broken Pieces, both currently on view at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, is like shifting between worlds. Bey’s photos depict the streets and people of Harlem in the 1970s, a place that to us in 2017 seems like a lost world, his use of traditional documentary black-and-white photography enhancing that sense of distance. Theodore’s larger-than-life, staged street portraits are less documentary than metaphysical or theatrical, evoking a mysterious future through the drama of the set-piece in the street.

Gods and heroes

Philadelphia native Shawn Theodore (better known as xST–check out Jennifer Zarro’s interview with him on Artblog Radio) fills the white cube of the gallery with large-scale (around 20” x 16”) giclée prints dominated by vivid, saturated colors and sharp contrasts. Through the use of dramatic poses set in empty, slightly decaying urban environments, Theodore has captured a surreal, almost supernatural world, inhabited not by ordinary people but gods and heroes taken from the pages of Greek myth or Octavia Butler’s experimental science fiction. His titles are almost as interesting as the photographs themselves–take “Capricornus Constellation, Black Hole Quasar,” for example, which depicts the close-shaved head of a young woman, as dark and mysterious as a celestial black hole, in sharp contrast to the pale lemon-yellow painted brick background. Her individuality is hinted at by her precisely defined, perfectly curled eyelashes and the elaborate pearl-studded collar that she wears, its shining spheres recalling the stars of the Milky Way. She seems not quite of this world, part of some grand celestial drama. Theodore has spoken about how narrative his photos are, and that he is not really portraying people as individuals as much as he is portraying people as archetypes.

Documenting daily life

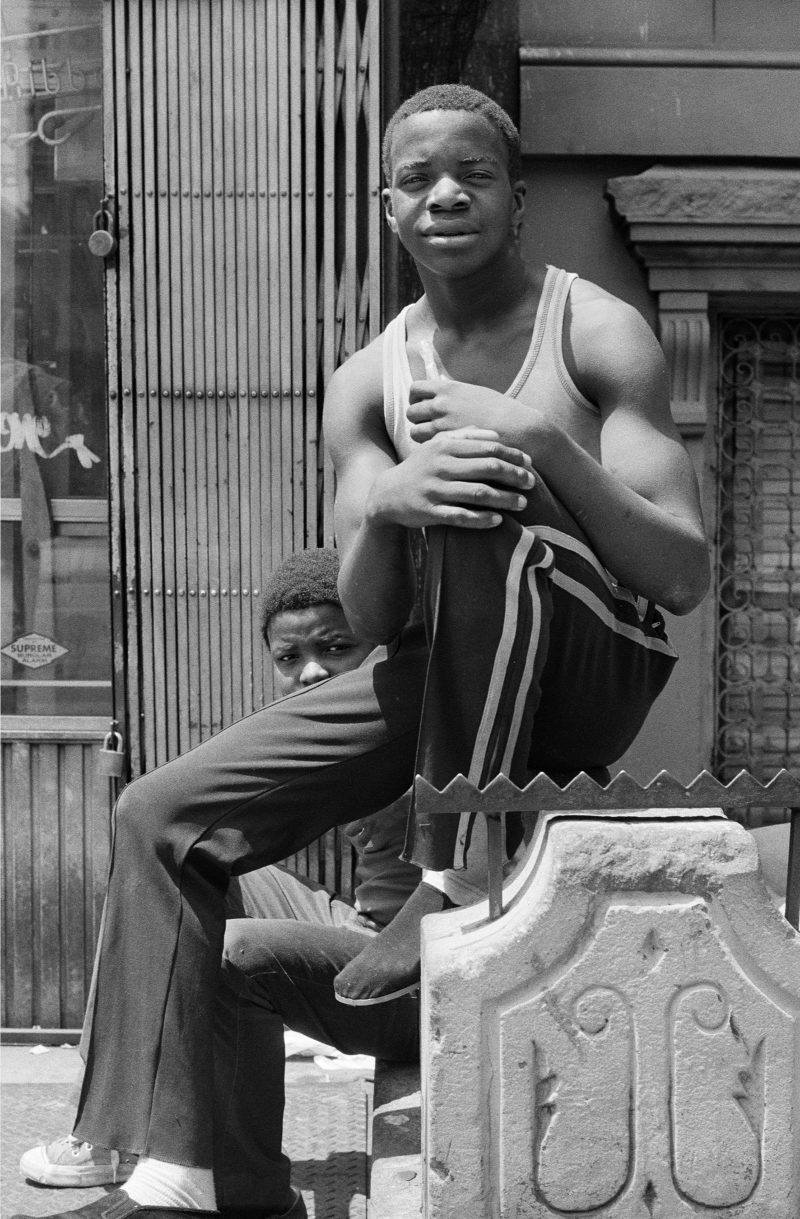

Bey spent years wandering the streets of Harlem with his small, 35 mm film single-lens reflex camera, becoming known to people in the neighborhood that his parents had abandoned in favor of Jamaica, Queens. His work shows a clear debt to photographers like James Van Der Zee, Roy DeCarava, and Gordon Parks, who documented the lives of ordinary black Americans, showing both the struggle and the beauty of life in Harlem. In interviews, Bey has said that he seeks to create a “momentary connection that would leave viewers feeling they knew this person.” But that connection is at best fleeting and partial. Looking at Bey’s Harlem residents as they stare forthrightly back at me, I feel as though I catch only a glimpse of their inner lives. With his folded arms and frontal gaze, the young man in the foreground of Bey’s 1976 “Two Young Men” seems full of confidence and bravado, but his companion who nearly hides behind him, his face caught in shadow, hints at a more complex story. This photo pulls me in, but reminds me that I am still an outsider.

Fleeting connections

Bey and Theodore both come from the tradition of street photography, and share the ability to capture the fleeting essence of their subjects–although Theodore seems to ask his viewers more explicitly, just how much can we know about any of the people in these photographs?

Let’s take two portraits of young women, for example. Bey’s 1976 “A Woman Waiting in a Doorway” shows a fashionably dressed young woman in a crisp white shirt, an exuberant bow tied at her neck beneath which runs a neat row of buttons on her tailored vest. There is a stillness to her, a poise, as she stands in a doorway, caught between shadow and light. Her face is slightly turned away from the camera, and her solemn expression seems to shut us out, emphasizing her interiority and subjectivity.

Similarly, Theodore’s diptych portrait entitled “I am what you see and what you cannot; African, American (1 & 2)” presents two views of a single woman’s face–the first in perfect profile, the sun illuminating her face and brilliant green head scarf, and the second a frontal view of her face half in shadow, her features obscured. Like the shadowed face of Bey’s waiting woman, Theodore’s “I am what you see and what you cannot” underscores the distance that separates subjects and viewers even in the most perfectly realistic or documentary photograph, and accords this woman a complex interiority that cannot be captured by the camera’s lens.

Dawoud Bey’s Harlem, USA, and Shawn Theodore’s The Church of Broken Pieces will be on view at the African American Museum of Philadelphia, 701 Arch St., through April 2.