At the Painted Bride Art Center’s gallery space, in an InLiquid show curated by Scott Schultheis, three artists with notably distinct techniques converge on themes of inquiry and discovery, ultimately arriving at a crossroads where science and speculation coexist in a strange stylistic harmony. For the exhibit “As By Digging,” Jaime Alvarez, Olivia Jia, and Michelle Marcuse share similar archaeological and observational sensibilities, although the paths that lead them to their final products meander through very dissimilar practices.

Remembered shantytown architecture of Michelle Marcuse

Michelle Marcuse provides an unmistakably architectural foundation for her creative experiments as she affixes bits of cardboard together to form tiny huts and hovels splashed here and there with subtle streaks of white paint. While the corrugated forms inherent in the original cardboard material, paired with Marcuse’s construction techniques, allude to materials like vinyl siding or sheets of corrugated steel, almost everything used is a repurposed paper product with a wood pulp origin. It is no surprise, then, that these glued-together, reconstituted pulp sculptures mostly resemble treehouses or shanties also built primarily out of wood. Marcuse seems to draw parallels between consumer and industrial waste, much of which comes into and then swiftly leaves our lives, ushered between locations that are largely out of view of the average person.

The complicated tangles of fragments that Marcuse utilizes for her tiny structures indicate a pattern of organic, haphazard growth over time, sifted from some sort of convoluted, hidden past. However nothing about history or science is as cut and dry as it appears in its polished, publicized form. Indeed, building a historical narrative, or fitting together facts to see a bigger picture is often a messy and arduous journey with as many twists and turns as those built into this artist’s perplexing array of hallways, columns, and stairs.

Documentary photography of Jaime Alvarez

Documentation is central to the photography of Jaime Alvarez, but there is a curiosity behind the candidness. His photos can be divided into two categories for this show: interiors and objects. The former finds Alvarez in the ramshackle rooms of abandoned houses which, no matter the state of disarray, seem considerably more stable and put-together than Marcuse’s shaky structures. In these scenes, the remnants of ornate wallpaper and flakes of paint cling to and peel off of the walls which enclose empty corridors with dusty floorboards. In “Bathroom Skull (5th Street Victorian Series),” a gnarly looking bathroom with bright peach-colored walls lies unused for decades, it seems, with the exception of the sneering, red, cartoon skull spray painted opposite the bathtub. Our attention is split as we imagine who the house’s original tenants might have been, as well as the more contemporary artist who has drastically altered their decomposing powder room. On both counts, we are left with merely a snapshot of two vastly divergent histories, and no evidence beyond our impressions.

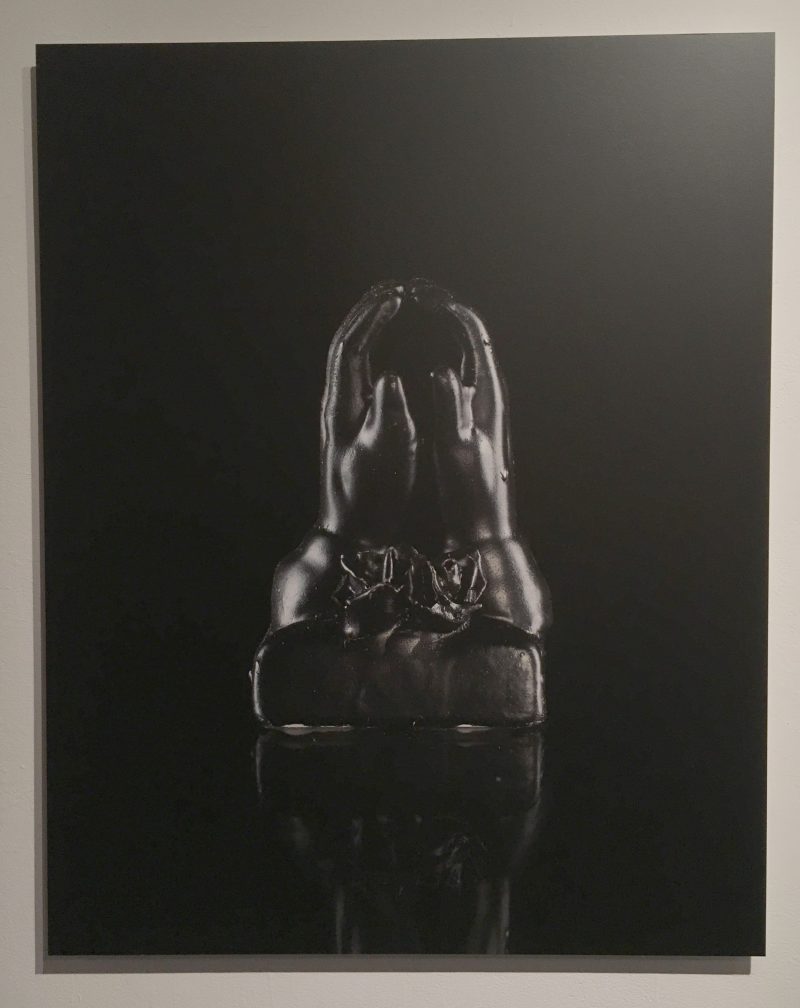

Alvarez also handles his object-based photos in a similar fashion. Utterly devoid of context, the photographer captures small, metal sculptures — presumably antiques — against black backgrounds so as to isolate them. It is also worth noting that the dark metallic exteriors of these tchotchkes tend to blend in with their empty settings, bestowing them with an intangible, spectral quality. The representations themselves are as enigmatic as they are untouchable: a pair of praying hands, a seagull, and an ice skater. Aside from a slight reflection from the surface on which they sit, these items are entirely isolated, and left to silently speak for themselves.

Archival materials lovingly depicted in Olivia Jia’s paintings

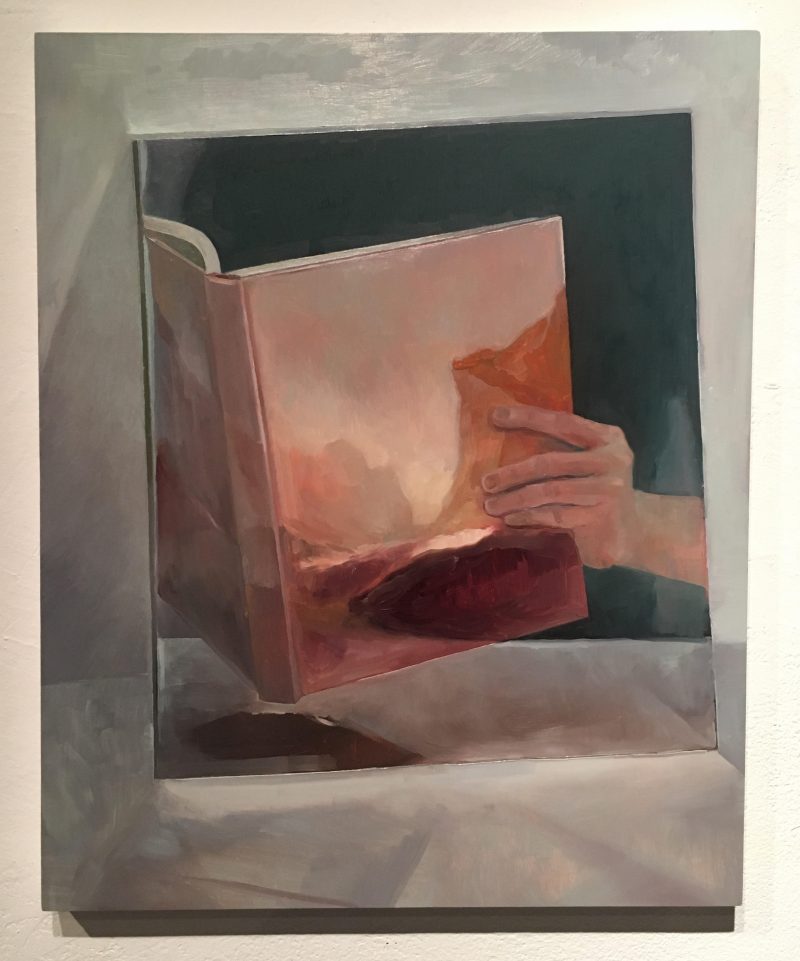

Wielding paintbrush and canvas, Olivia Jia recreates archival materials from museums, such as images of statues or slides. In the backdrop of a cathedral or museum collection, a well-weathered bust contains clear messages about its time, its purpose, and possibly its creator. Reformatted into a two-dimensional facsimile, no matter how faithful to the original, an ancient face becomes much more difficult to place. Jia does tend to abstract her subjects ever so slightly, making their specificity even harder to grasp. In “Untitled (Bierstadt Book),” without glancing at the title, and perhaps a quick clarifying search query, the origins of the orangey-pink tome remain quite obscure. How much does a Hudson River School painter really influence our understanding of this image? What does the anonymous hand reading a nameless book mean without any knowledge of Albert Bierstadt?

In Jia’s piece “Slide, (O),” a painted reproduction of a slide, which is itself a reproduction of a nephrite jade sculpture, the frame-within-a-frame resembles the screen of a tablet or mobile device. Nothing could be further from the truth, however, since although this piece straddles the preservation of ancient history, photographic documentation, and contemporary oil painting all at once, any digital associations are pure conjecture. Outside of a museum setting and factual chronology, though, speculation is far from an ahistorical sin, and even a false hypothesis can help us get closer to the truth.

Artists, much like scientists and historians, are diggers and storytellers. While art is distinctly more personal, and sometimes abstract, in comparison to hard science, it often utilizes many of the same mechanisms to explore the world around us: observation, assessment, and exposition, just to name a few. Any one method might tell us an awful lot about what we perceive, but without looking at something from every possible angle, there is also plenty to miss. This is, of course, why the role of the artist is indispensable. By interpreting cerebral issues through a humanist lens, artists like Alvarez, Jia, and Marcuse offer intuitive and emotional commentary to otherwise empirical considerations. These responses informed by experience and memory do not undermine facts and measurements, they merely carve out a niche for the individual within the vastness and complexity of the truth.

CORRECTION: This post originally omitted that “As By Digging” is an InLiquid exhibition curated by InLiquid’s emerging curator, Scott Schultheis. We regret the error.

“As By Digging” with Michelle Marcuse, Jaime Alvarez, and Olivia Jia, will be on display at the Painted Bride Art Center until January 7, 2018.