Becky Suss is a native Philadelphia artist known for her large perspectival paintings, reminiscent of playful architectural renderings, that capture intricate domestic territories. The resulting vignettes portray the idiosyncrasies of interior living, personifying her subjects through curated compositions of household objects. In her earlier work, shown in solo exhibits at the Institute of Contemporary Art and most recently the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York, Suss draws from memory to derive alluring scenes that psychoanalyze familiar settings, such as the interior of her grandparents’ suburban home.

Esherick’s personal effects and Suss’s dynamic paintings

Currently on view at the Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, her latest exhibit, Becky Suss/ Wharton Esherick, explores new territory inspired by an experiential residency at the Wharton Esherick Museum, the former home and studio of artist and pioneering craftsman Wharton Esherick. Hailed as the Dean of American Woodworking, Esherick is known for his sculptural and folksy interpretation of utilitarian objects such as utensils, tables, chairs, and built-ins. Accompanying Suss’ work in the exhibit are furniture, sculpture, and personal objects sourced from the museum, many of which are captured within her dynamic paintings.

Imagine falling down a rabbit hole and landing in a hallway. You curiously peep into a tiny door and discover an enchanted scene exploding with churns of color, shapes, patterns, and strangely familiar objects. Suss’s work evokes a similar sensation as she paints apertures into Esherick’s life through the whimsical self-built interiors of his home. A painted elevation of Esherick’s red oak drop leaf desk straddles the right gallery wall, opened to expose an intricate structure of files, books, and various stationary items. Suss’s exemplary use of detail, pattern, and color present a refreshing perspective on the mundane. It is like returning to a familiar place only to discover something you had never noticed. Reflecting on a recent visit to the Esherick Museum, I felt movement in the textures depicted in Suss’s paintings. She accounts for every single grain of wood in the desk, dimple in the stone wall, and plank in the wood floor, and I was tempted to run my hands across the surface to check for an unfinished patch or splintering relief carving.

The joys of trespassing

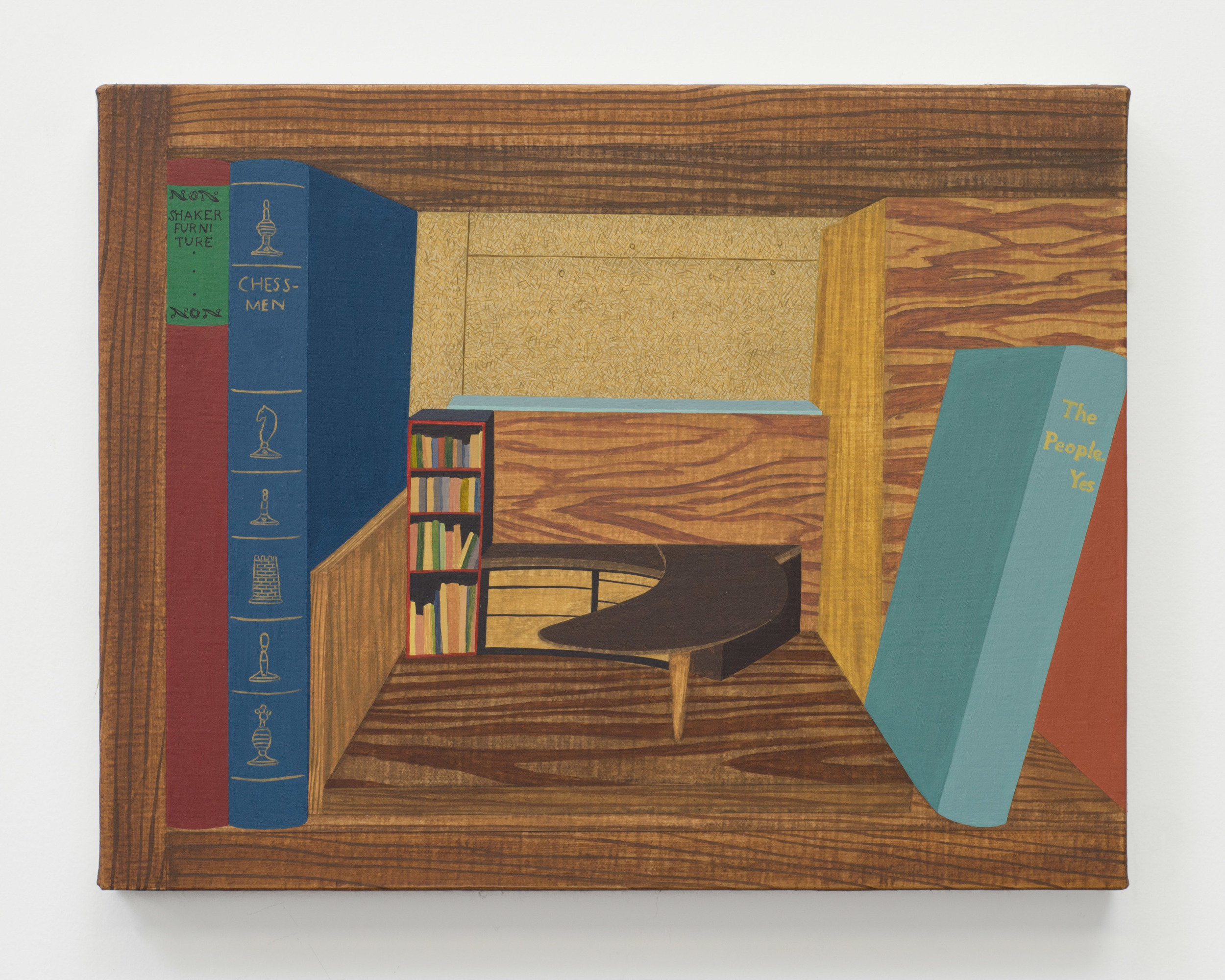

There are no inhabitants in Suss’s paintings, only empty spaces that evoke trespassing. Accompanying these larger works are still-life snippets of personal articles that elicit a sense of curiosity and devious pleasure — as if you stumbled upon these hidden marvels while sleuthing around. A magnified view of the patterns on a pillow belonging to Letty Esherick (Esherick’s former wife) and the front cover of a children’s book written by friend Mary Marcer and illustrated with his woodcuts can be found among the collection. One of the most captivating glimpses that Suss gives us is of the tiny wooden models, maquettes, that Esherick made to pitch his designs to clients. Now retired, these artifacts seek refuge in the voids of a wooden bookshelf between neighboring titles: Chess-men, The People Yes and Yachts Under Sail. Complementing the painting is Esherick’s actual maquette, a proposal for wall shelving and storage, depicting micro-scale knick-knacks, vases, books, and anticipated personal items collected on the shelves.

I pass by an object, one of Esherick’s many renowned built-ins, an upholstered rounded-crescent sofa made of cherry wood that chamfers* the gallery corner. Other objects hover. A collection of his books levitate on a nearby shelf, flanked by two bird-like cast-metal sculptures titled “Babbie” and “Colt.” It’s tempting to plop down and make myself at home in this improvised reading nook.

Peering into the painting of the Esherick room across the way, I feel as if I’m stuck inside a dollhouse. The space is composed as a stratum of contrasting horizontal elements. My eye is naturally drawn to the center, out a narrow ribbon window, and into a wooded abyss. A docile woven-rug is curled up on the floor. Above, a subtle checkered print blanket is draped over a tomb-like wooden storage compartment, where Esherick kept his yellowed-collars shirts — the exact ones exhibited on the nearby gallery shelf, as if picked from the drawer and neatly stowed aside.

A life in detail

Across the room, I glimpse the painting of Esherick’s kitchen/dining area. It appears to be a pleasant summer day. Hand painted ceramic plates created by Esherick’s daughter Ruth and son Pete hang from the wood-paneled walls. I can envision Esherick sitting at the empty table peering out the large framed window over Valley Forge. Suss renders the variety of wood species that compose the inclosing floor, ceiling, and walls using variations in tone and scale. The resulting patterns create a psychedelic vortex as your eye is drawn to the center of the composition. It feels as if the space is moving around you. Adjacent, Esherick’s own wooden bowls and cutting board adorn the gallery wall alongside a display of ceramic plates and bowls made by friends.

Suss’s work distills the vulnerability and character of domestic space, offering more than just a peek inside. Her painted portals transcend layers of time, amalgamating the forty-year masterwork that was Esherick’s home. The vacant yet exuberant interiors conjure both nostalgia for and curiosity about the life of the elusive craftsman. Imagine if work like Suss’s could replace the staged photos in real estate listings or home furnishing catalogs. Perhaps then we would better appreciate the craft involved in creating our own domestic refuges and discover the beauty in conventions of everyday living.

“Becky Suss/ Wharton Esherick” is on view November 16, 2018 – January 26, 2019 at the Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, 1216 Arch Street, 5A, Philadelphia, PA 19107; Gallery Hours: Tues–Fri: 10:30–5:30, Saturday: 12–5; phone: (215) 545-7562

*In carpentry and architecture, to chamfer is to cut away a right-angled edge or corner to make a symmetrical, sloping edge

More Photos