In Legends Never Die: A Collective Memory, Guadalupe Rosales makes a case for the role of the artist as curator and preserver of history when official accounts fail to tell the entire story. I grew up in the Los Angeles where everything is pronounced with the flat, afflectless, accentless casualness: “Lawss An-juh-less;” where Watts is the location of field trips to see Simon Rodia’s Towers and where Dodger Stadium is only a baseball field and not a monument to the violent displacement of inhabitants of the Chavez Ravine neighborhood that took place in 1959 before the Stadium was built.

So Rosales’ show, on display at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, presents (to me) an entirely new side of the city that certainly hasn’t gotten the Hollywood treatment afforded to the Beverly Hills world of Clueless.

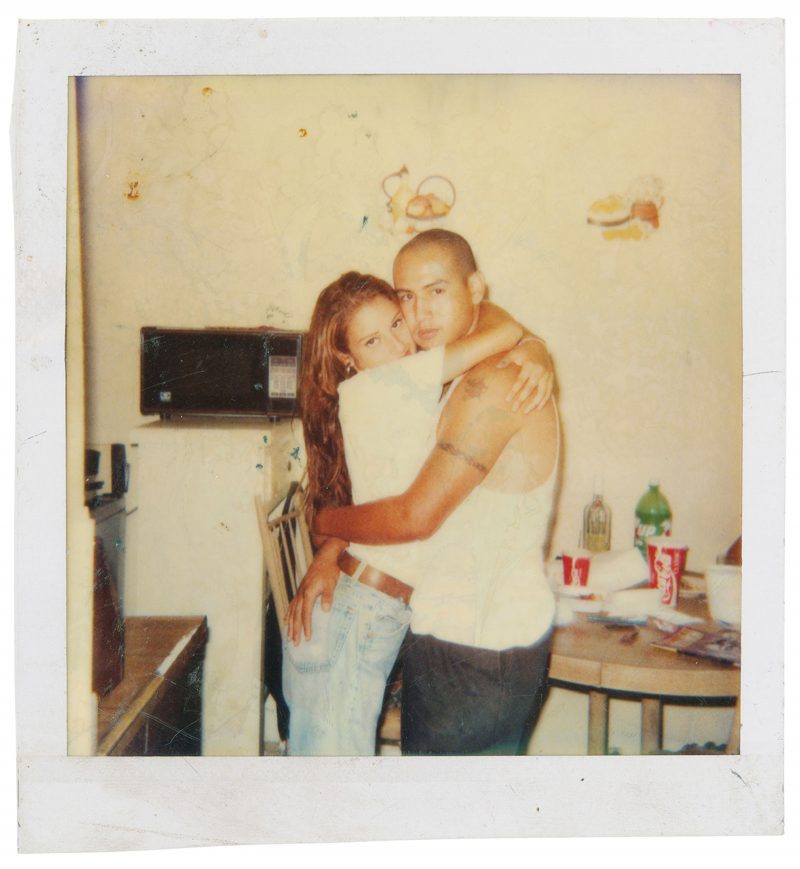

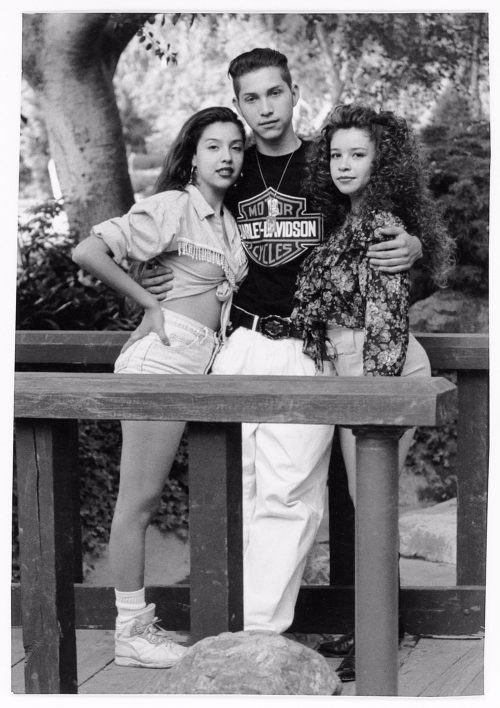

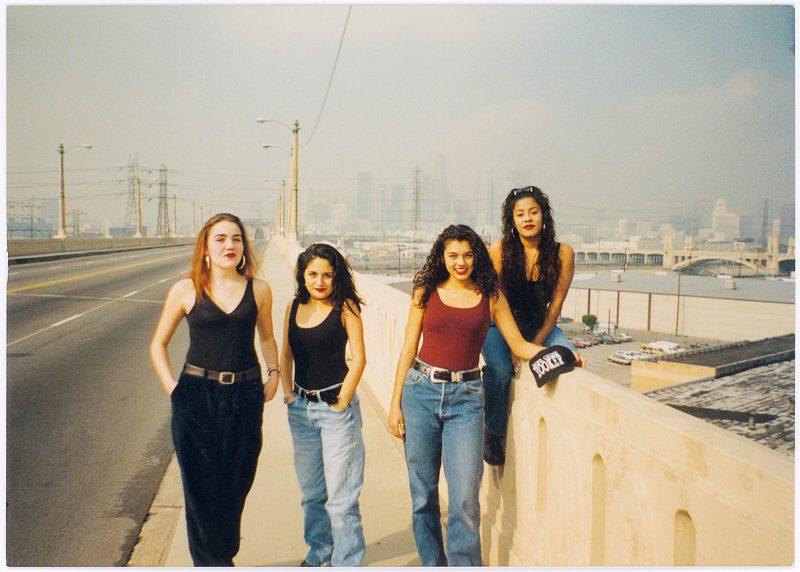

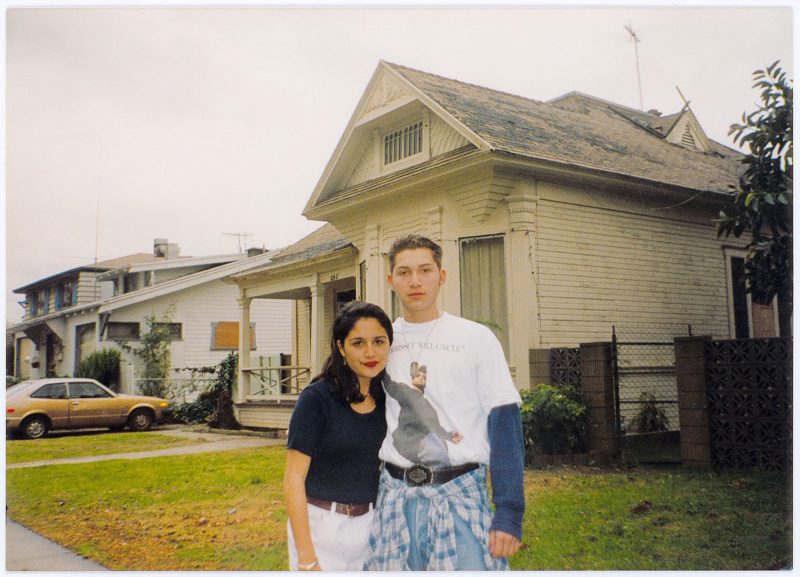

The exhibition of color and black and white archival photos is a physical presentation of the work Rosales has been doing for years seeking out, collecting, and sharing photographs, video clips, and other assorted objects that tell stories of 1990s Chicanx culture; accessible through her Instagram accounts Map Pointz and Veteranas and Rucas and featured in the fall 2018 issue of Aperture, Legends Never Die takes on a new level of intrigue when viewed in a dedicated setting.

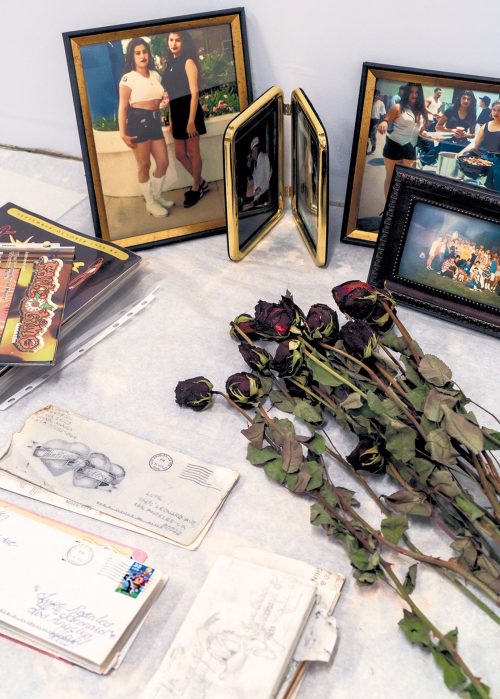

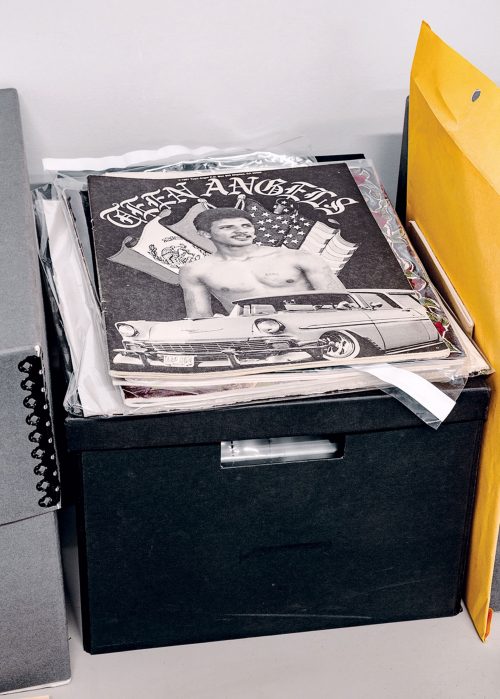

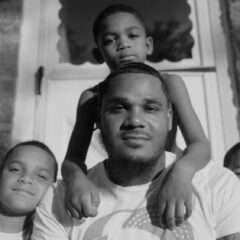

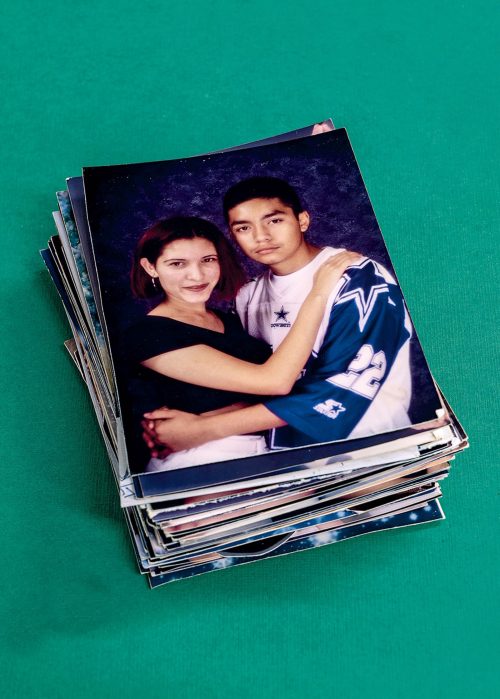

The dark interior and purple lighting of the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery combine with loud music playing in the background to evoke the feeling of a nightclub. The setup itself is extremely spare, with a horizontal glass case placed slightly off-center, with a slideshow of Rosales’ collected photographs plays across the room, interspersed with fuzzy video clips of the Chicanx community, of young Latina women enjoying themselves, as Rosales’ accompanying text notes. A photocollage covers the back wall of the space, filled with portraits and candids alike, mixing photos from Rosales’ past with photos she has collected. The glass case presents photography and artifacts of the childhood Rosales experienced, combining flyers and posters for parties with magazine covers, a black bandanna, formal family pictures taken in a studio. By combining images from her youth with images and artifacts donated by other people who were part of this world, Rosales presents the power of collective memory, and the empathy that shared experiences has undoubtedly created for her over the course of her work.

You’ve been invited to an unabashedly cool rave scene just by entering the gallery, like the flexible space has adopted attributes of the kinds of parties advertised in the glass case. But the purple lighting takes on a melancholy air, when you consider the shrine off to the side of the room, a tribute to Anthony Alonzo, a boy who was part of the underground party scene killed in a hit and run outside a party in 1995. A sweatshirt belonging to Alonzo hangs above a small stack of votive candles, a beaded cross, a bandanna, comprising an isle of solemnity amidst the pulsing energy of the space, creating a sense of emotional whiplash that is likely more powerful in person than via Instagram or glossy magazine pages.

Legends Never Die is not merely about the artist as public servant, as curator and archivist of memory, but about the changing role of the artist in their community as their community changes in turn. Indeed, the most engaging aspect of the installation comes in the juxtaposition of the different kinds of storytelling Rosales engages in: on the one hand, the gallery displays her carefully preserved mementos, her efforts to publicize this under-discussed Chicanx history via social media; on the other hand, Rosales presents her own struggles in returning to her home neighborhood of Boyle Heights in “The Town I Live In” (viewable here), a ten-minute video essay presented outside the gallery space as if to assert its own factuality.

Boyle Heights has made headlines over the last few years for its staunch activist movement, represented by Defend Boyle Heights and Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement that has opposed art galleries, hipster coffee shops, and other harbingers of gentrification moving into the area and displacing longtime residents. These movements are quite clear about what what they oppose, recognizing that gentrification can be perpetuated by people of color as well as the archetypal white business executives, and that “artwashing” and other hallmarks of redevelopment, investment, and “progress” can endanger communities by leading to increased police surveillance.

Rosales spends her time immersed in mementos of her childhood in Boyle Heights, where gang violence marked the streets as well as her own life, and expresses her desire to see her community become safer and more livable. Yet as presented in her video, Rosales’ efforts to reconnect with Boyle Heights have faced opposition from groups like Defend Boyle Heights, who argue that she and the local galleries and arts organizations she has tried to work with are promoting gentrification. Rosales asks: what is good versus bad change in a neighborhood where there used to be shootings? The neighborhood has indeed seen an explosion of development in recent years, ranging from for-profit galleries to the nonprofit collectives PSSST and 356 Mission, both of which Rosales hoped to engage to exhibit her work.

For Rosales, though, the final straw appears to be the boycotting and protesting of Self Help Graphics & Art, a local institution operated by Joel Garcia that existed in Boyle Heights for decades and has fought against gentrification in other parts of the city–hardly the same air as a ritzy gallery that swoops in and takes advantage of low property values, right? Indeed, its return to Boyle Heights in recent years, and its purchase of the building it resides in, has been cast as a win against gentrification. Yet further research on my part reveals a few reasons that activists might have to keep Self Help Graphics & Art at arms’ length: its close relationship with developers and city council members (see here and here) who may have aided it in resisting displacement, but who have also contributed to further displacement in Boyle Heights.

As relayed by Rosales in “The Town I Live In,” it’s not quite clear what anti-gentrification activist groups like Defend Boyle Heights and BHAAD are for, although the video admits that none of these activists were willing to be interviewed. We are necessarily getting one side of the argument, framed almost as documentary but clearly meant to be persuasive, calling for nuance. Yet Rosales does not contextualize the reasons these activists might be against her coming back. Rosales is no longer a truly local Boyle Heights artist–she’s now a nationally-known name, with multiple presentations of Legends Never Die at venues like Aperture Gallery in New York (and Aperture’s eponymous publication) as well as at Haverford College. She was also the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s (LACMA’s) first Instagram artist in residence, and was invited to take over the New Yorker’s social media as well, further giving her the imprimatur of the establishment, of the rarefied art world that Boyle Heights activists oppose. Being concerned about “gentefication,” or “upwardly mobile, college-educated Latinos return[ing] to their old neighborhood and invest[ing] their time, money, and interests” is within activists’ purview and rights, and seems to apply to Rosales herself, even if she remains tied to her neighborhood by memory and by practice (City Lab) . Asking the question of whether Defend Boyle Heights and its ilk are against the idea of art itself risks oversimplifying the complexities of the issue.

Legends never Die: A Collective Memory is on view at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery until March 8th, 2019.

More Photos