To say Art is for everyone, similar to saying Black Lives Matter is to assert a truth that is not reflected in the world. While cultural institutions can be the garden where beliefs and reality grow together, these institutions have historically not tended to the experiences of marginalized folks. Still, they claim art is for everyone. Responding to this epidemic of exclusion is Women’s Mobile Museum (WMM), a project that gave ten Philadelphia women and femme artists creative, financial, and social support to help them produce bodies of photographic work that told their own stories.

For the last year WMM has centered its programming around the question, “Who is art for?”. WMM aimed to cultivate some of the underrepresented voices in our city and find an answer. With sponsorship from Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC) and under the leadership of renowned South African photographer Zanele Muholi and Lindeka Qampi, The culminating shows, on view at PPAC until March 30th (as well as at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art to March 31ST), are filled with photography from these participants, as well as from teaching artists Zanele Muholi and Lindeka Qampi.

As it’s name would suggest, Women’s Mobile Museum is not a museum defined by its location. The project encompasses the qualities of a museum through its thorough research, accessible displays, and large collection of work. The exhibition at PPAC is fully submersive and chooses to prioritize the personal histories of each artist. An introductory video, created by Anula Shetty and Cindy Burstein, introduces each artist and interviews them to learn more about who they are and why the work they are making is important. In addition, there is an audio tour of the show, which in addition to some visual descriptions, features each artist reading their own artist statement. The result is a gracious display of self, made possible by tutelage of Muholi and Qampi.

Muholi is a world renowned photographer who has primiarly focused creating portraits of black LGBTQ people. For this residency they have continued their recent practice of turning the camera around and making self-portraits. Muholi’s signature style remains; every photo is black and white with their skin made into a deep black. Their eyes, which are always meeting the viewer in a mutual acknowledgement, are focal point of each photo. Muholi often transforms their body through adornment. In “Sizwe I,” Philadelphia, they wear an outfit made from the long grass that fills the field in which they lay. Propping themselves upright, Muholi gazes defiantly as their body melds into the waves of grass. Similarly, Qampi utilizes adornment in her self-portraits. In her series, “Inside My Heart,” Qampi has fashioned clothing out of recycled materials to communicate the strength and dignity that can be found in people who have been harmed by violence.

Self portraiture that tells stories and builds empathy

Artists Davelle Barnes and afaq are also engaged with how images of the self can build empathy. Sharing an alcove in the gallery space, the two photographers engage with the consequences the United States military has brought onto their lives. Barnes’ photo series, UNSAT, seeks to honor veterans, including herself, harmed by the military’s racist and homophobic behaviors and policies. Her largest photograph is a vinyl print that fills the wall. Barnes explains that the photo, “Present Sky,” is, “a signal to the world [that] black women are participating in war at record numbers despite public perception created by the mainstream media which favors hero stories about white men. The image has us looking up, behind her as she stands in full uniform, giving a salute to the engulfing blue sky.

afaq, a visibly muslim woman, aims to disrupt the western gaze by sharing beautiful close-up shots of her face. Her series, “untitled [zola] / [zola] untitled,” presents proud depictions of a muslim woman, contrary to the islamophobic depictions perpetuated by the United States. Accompanying the images are a series of short poems. The text appears directly on the wall and is scattered under and between photographs. They offer insight to the political and militarized persecution afaq has faced as well as confessions about her struggle to find emotionally solid ground. The first one reads, “i am sudanase/born in yemen/i have yet to love a country/that did not try to kill me.”

Stories of displacement, in self portraiture and in representation of others

Displacement is a recurring theme throughout WMM. Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Iris Maldonado grapples with her inability to return to her home and the desire to have a full sense of self despite intense feelings of loss. Her self-portraits are sensual, often featuring Maldonado’s partially nude body against soft fabrics and flora. There is a passion for life emanating from Madlonado’s sturdy gaze and elegant posture. Muffy Ashley Torres similarly implicates their own body in photos that address the burden of grieving a home. In “Demolished,” Torres sits on what remains of a gate post. A mountain of rubble rests behind them. They cradle a single brick as a tender reminder that this object used to make up a home.

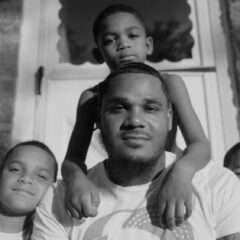

Tash Billington focuses on those who have resisted displacement here in Philadelphia. In her portrait series, “Philly Natives,” she takes photos of individuals who were born and raised in the city. Despite forces of gentrification, incarceration, and poverty, they have remained. Shasta Bady also looks towards Philadelphians for inspiration for her body of work, “As Above, So Below.” While travelling on SEPTA, particularly on the Market Frankford Line, Bady waits until someone captures her interest and then takes a photo. The portraits are at times surprisingly intimate and show the vibrancy that each human holds — something that is easily overlooked when travelling on public transportation.

Taking a different approach to representing a city is Danielle Morris. Her series, “Larchwood,” focuses instead on a single home. Morris mystifies her childhood home by giving only fleeting glances of activity; a woman is bent over as she washes her hair in the kitchen sink, a television displays static in an empty room only dimly light by a warm lamp, an arm wearing five watches reaches up in front of a distant wall with a clock sitting on it. Her most striking photo, “politics,” is an aerial of a lit gas stove, a hot comb resting on top with a jar of vaseline and a paper towel scorched from the comb. Because of the controlled composition, the scene, which is familiar to many people raised as black girls, is both familiar and strange. From here, Morris allows for rumination on the implications of the practice of straightening hair.

Andrea Walls and Shana-Adina Roberts provide exceptional photographs that experiment with showing the tension between presence and absence. Andrea Walls’s “Sought: Sanctuary Between Church & Estate” presents an image of a church interior. In the middle of the image, a stained glass window emits a glow into the sanctuary. A woman resting her hand on a wall is superimposed into the room, making it seem as if she is standing in the middle of the room. Her shadow is also present, making the image appear to show two translucent figures experiencing a moment of connection in this holy space.

In Shana-Adina Roberts’ photo, “I Whisper In Silence My Presence,” a figure in a dim room is backlight by a tall window while simultaneously standing behind a sheer curtain. Her arms reach out so that her hands are visible outside of the curtain. They are the only parts of her body that are clear. In front of her is a large house plant that seems to mimic the motion of reaching out.

Carrie-Anna Shimborski steps into a curatorial role for her body of work, “One of Eight.” She shares a collection of family photographs and tells the heartbreaking story of why there are no pictures of her mother with her own parents or guardians. Shimborski brings to attention something that is evident in the viewing of WMM; we feel more whole when we know the images of ourselves are valued.

Photography is likely the best medium to address issues around representation and art. Our interaction with photographs, unlike with paintings and sculptures, is personal. When we see ourselves and people like us in cultural spaces, we can start to believe that the art there is for us.

Women’s Mobile Museum with Zanele Muholi is up at Philadelphia Photo Arts Center through March 30, 2019. 1400 N. American St., Suite 103.